|

Donald

Campbell inherited Sir Malcolm's taste for adventure,

plus of course a Bluebird boat to start him on the

trail to a LSR and WSR career, purchased for a nominal

fee, after Sir Malcolm passed away in 1948. The

K4 was converted from propeller drive to jet engine,

but Major Halford from de Havilland was disinclined to

to see Donald use it because of his inexperience.

Accordingly, he asked for it to be returned. Hene

Vospers were asked to convert it back to propeller

drive, which pleased Leo Villa. All that

remained was to fit the Rolls Royce engine, then on

10th August, Donald made four runs and later in the

week experienced a scary moment or two but

nevertheless did not let up.

Donald

Campbell

Reid

Railton brought it to the attention of the team that

Stanley Sayers boat used a special propeller that

enabled the boat to lift out of the water - a prop

rider. Reid Railton had seen K4 in action and noticed

it rise a the rear, causing the nose to point down

into the water. After this Donald wanted to

convert the boat to a full-blown prop rider. Lewis and

Ken Norris were commissioned to do the design work.

The engine was moved forward to alter the centre of

gravity, and the seat was relocated on the port side.

A new propeller was also specified.

During

this conversion Donald was invited to enter the

Oltranza Cup, an Italian event. The race took

part on Lake Garda. This was four laps over a 5-mile

triangular course; with the winner winning the Grand

Prix for the fastest overall speed and the Oltranza

cup going to the boat that set the fastest time over

two consecutive laps.

The

race took place on the 10th of June after being

delayed due to bad weather. After failing to

start the engine, the ywere forced to change all 24

spark plugs. Because of this they had no chance

of winning the Grand Prix. They could however

still win the Oltranza cup. Leo Villa accompanied

Donald for a rather exciting ride. The K4 took a

bit of a pounding smashing many instruments. The

ride was sufficient to draw a few choice words from

Leo as to Donald's performance. However they won

the Oltranza cup by a convincing margin. This

win did wonders for Donald's recognition for his

skills as a driver. So began Donald's career in

fast boats.

Donald

suffered a 170Mph crash in 1951. As a result of

this crash he developed a completely new boat, the K7,

after enlisting the services of a brilliant designer Ken

Norris. Ken had earlier worked on the ill

fated White

Hawk K5 jet hydrofoil boat. The resulting K7

was to prove a formidable steed that saw him set

7 World Water-Speed records between 1955 and 1964.

The first was at Lake Ullswater where he set a record

of 202Mph. This was raised to 216mph at Lake Mead in

1955. Then began a sequence of record raising

runs at Coniston where he attained 248mph in 1958.

But to really push out the boat record wise he went to

Lake Dumbleyung, Australia, where the K7 set a new

world records of 276mph in 1964.

The

K7 first run 4 January 1967

Donald's

career spanned 18 years and finally end in tragedy on

Lake Coniston, where he was trying to best his own

record to drum up sponsor interest. In addition,

there was a prize for each time the water speed record

was broken, which it is believed the speedster benefited

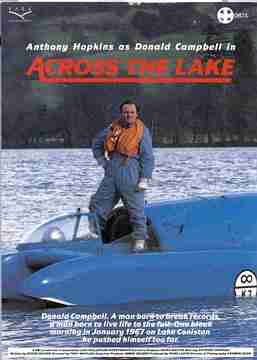

from during his 12 year career on water. This tragedy

was later made into a film to commemorate the great

man starring Anthony Hopkins as Donald Campbell, named

'Across the Lake'. Unfortunately for many

enthusiastic about the BBC docudrama, the film is not

on general release.

A

heavier, more powerful gas turbine engine was fitted

to K7 and the position changed so as to correct the

boats trim. Donald had overspent keeping his

crew on while waiting for a break in the weather.

Determined to give the Press a show to make their wait

worthwhile, at around 8:30am Donald clambered into his

boat. An army of photographers had been camped by Lake

Conniston waiting for something to happen and this was

it. To the amazement of all gathered to record

the event and with shutters clicking for all they were

worth, the K7 gracefully took to the air, somersaulted

and nose dived into the lake. There was a

stunned silence for quite a time before somebody

reported over the radio: "There's been a

complete accident. No details. Over." Although

the wreck was not recovered, the K7's insurers made an

ex-gratia payment to the estate of Donald Campbell

against this total loss.

He

was travelling at more than 300mph (483 km/h) on

Coniston Water when the boat was catapulted 50ft (15m)

into the air after its nose lifted.

Forty-six-year-old Mr Campbell was killed instantly as

the boat hit the water and immediately

disintegrated. He

was just 200 yards (183m) from the end of the second

leg of his attempt when the accident happened.

This sequence is almost identical to an incident

involving Slo-mo-shun in 1950. Indeed, John

Cobb was to suffer a fatal crash in his jet

propelled hydrofoil boat, Crusader.

After

a swig of coffee laced with brandy, Donald Campbell

slid into the cockpit of Bluebird K-7, his lapis blue

colored hydroplane, gave a thumbs-up, and ignited the

4,000-pound-thrust jet engine. Since 1955, he

and Bluebird had cheated death to break the water

speed record seven times. When he captured the land

speed title in 1964, Campbell became only the second

person besides his father, Sir Malcolm, to hold both

records. Throughout the United Kingdom, the Campbells

were legendary and the Bluebird an icon.

There

wasn't a hint of wind as Donald Campbell throttled to

the other end of the mirror smooth lake. Within

seconds, he'd raced through the measured kilometer, at

297 mph. "Full house!" he radioed. Campbell

had just gone 21 mph faster than anyone had ever gone

before, putting him in a place where the effects of

air and water on a boat were a mystery. But to

establish a record sanctioned by the UIM (Union

Internationale Motonautique) the powerboat governing

body, requires two runs through the trap in opposite

directions within an hour. Impatiently, Campbell

started his second pass driving into the ripples left

by his own wake. At 200 mph, his eyeballs began

oscillating as he hammered across Coniston water.

"I can't see much, and the water is very

bad," he said. At around 300 mph, Campbell felt

like he was riding a turbine-powered vibrator. "I

can't see anything I'm having to draw back [on the

throttle]." Suddenly, Bluebird lifted

off the lake. "I've got the bows up!" he

said. "I've gone... oh... "

On

the first leg he had reached speeds of 297mph

(478km/h), which meant he had to top 308mph (496km/h)

on the return journey. Initial reports suggest

he had actually reached speeds of up to 320mph

(515km/h). This means the water speed record of

276.33mph (444.61km/h), which Campbell himself set in

Australia in 1964, remains unbroken as both legs of

the attempt were not completed. Had he broken

this barrier it would have been his eighth world water

speed record.

Bluebird

K7 crash 4 January 1967

Thirty-four

years later a salvage operation led by Bill Smith,

finally raised the wreck of the K7 to the surface of

the lake. Tonia Bern-Campbell witnessed the

landing of the craft. Donald's body had not been

located by this time, but the search continued apace

and with the aid of modern sonar equipment, Donald's

body was also recovered two months later in May 0f

2001 and laid to rest. May he rest in peace.

The

salvage operation started in December

2000 when divers

testing underwater cameras came on the wreckage.

Underwater surveyor, Bill Smith found the wreck at 150

feet half buried in silt. Donald Campbell’s body was

never found at the time of the tragedy. In March 2001

Bluebird was recovered from the lake bed . Campbell's

widow Tonie Bern Campbell, 64 watched it emerge from

the lake. The tail was undamaged but the front cockpit

area was completely crushed.

The Coniston Institute and Ruskin Museum Charitable

Trust now want to provide a permanent home for the

remains of Bluebird and are seeking permission for a

10m by 10m extension to the Museum to house it. The

application is supported by a letter from the Curator

of the museum stating that Bluebird is part of

Coniston’s heritage and the people of Coniston

"believe most strongly" that the craft

belongs in the town as a "permanent memorial to a

great British hero".

In August 2001 the Barrow in Furness coroner decided

that based on DNA evidence the remains found near the

wreck of Bluebird were those of the late Donald

Campbell. His daughter, Gina Campbell, 51, from Leeds,

can at last officially hold an official service

following the loss of her father, who died when she

was just 17. DNA

tests taken from her and compared with the remains

found in the water were confirmed as matching.

The

funeral service at Coniston Parish Churchyard took

place in September 2001. Donald Campbell has finally

been given a permanent headstone on the edge of

Coniston Water 35 years after his death. Family,

friends and those involved in the salvage of the

record-breaking Bluebird, were present at the moving

service in St Andrew's Church, Coniston.

The headstone features a carved bluebird and replaces

the temporary stone, which has been moved to the

Bluebird Cafe. The salvage team is to bring back a

fully working and faithfully

restored Bluebird and house it in Cumbria but lacks

the funding.

The restoration project could take up to three years.

“Bluebird”

has been in storage in the northeast since she was

raised from the bed of Coniston Water in March 2001 by

a team of divers led by Bill Smith of Newcastle. Now

Lake District planners have approved plans to extend

the village’s Ruskin Museum to house the boat in a

permanent exhibition celebrating the record-breaking

achievements of Donald Campbell and his father,

Malcolm. Applicants the Coniston Institute and Ruskin

Museum Charitable Trust have been granted permission

to build a 33ft by 33ft extension to the museum

The

K7 wreckage recovered 8 March 2001

One

of the most controversial acts to have taken place at

Coniston in recent years was the raising of Bluebird

from the lake bed during the spring of 2001. It is

probably fair to say that the majority of those born

and bred in the village were against any form of

salvage. The general opinion was that the wreck should

be left where it had been lying for the previous 34

years.

Nevertheless, the project continued despite local

misgivings. The position of Bluebird had been

accurately located the previous August. This had

created quite a significant risk which was that

souvenir hunters would systematically start to strip

the wreck. There was also a feeling within the

Campbell family that the wreck should be

raised, restored and put on permanent display in the

village. As a result, the salvage operation commenced

in February 2001, unfortunately without any

consultation with the community of Coniston for their

opinion or approval.

Despite this initial unsympathetic approach it has to

be said that the project to locate the boat and the

subsequent salvage, which was carried out by Bill

Smith of Newcastle, was a triumph of skill, stamina

and technology. To the lay person a project to raise a

wreck, which was only 150 feet below the surface,

might seem easy. In reality the difficulties were

immense. It is impossible for us to understand the

extremely hostile conditions existing below the

familiar surface of our lake.

Salvage

operations started with the assembly of two large

barges on the car park of the Bluebird Café at the

lake shore. Once completed the barges became a

floating platform which could hold the lifting crane

and the mass of underwater equipment needed for the

salvage operation to proceed. The platform was

launched on March 2nd, towed out to a point

above the wreck and secured with ropes to concrete

blocks which had been placed on the lake bed.

Next

day, with the assistance of a remote operating vessel,

divers started to secure lifting lines to the wreck.

Once complete the delicate operation was started to

lift the craft clear of the thick glutinous mud on the

lake bed, without causing any further damage. This

took several days and was completed on March 7th

with the help of hydraulic lifting bags. By the close

of play that day Bluebird had been raised from the

lake bed and was hanging from the floating platform,

just below the lake surface, by its lifting lines.

Tonia Berne

Bill Smith raises the K7

The following day the salvage was completed. The team

arrived at the Bluebird Café at 4:30 am, to be met by

TV crews who were already in position. Once out on the

platform Bluebird was checked and found not to have

suffered any harm after a night suspended from the

lifting lines. When all was ready the securing lines

holding the platform to the blocks on the lake bed

were released and the platform, with Bluebird hanging

underneath, slowly moved up the lake towards the

Bluebird Café.

A large crowd had assembled by this time to watch the

operation. When close to the shore the lifting bags

were deflated and Bluebird was allowed to settle back

onto the bed of the lake while the recovery trailer

was brought into position. The team knew that lifting

Bluebird onto the trailer was never going to be an

easy job, but eventually all was secure and the

recovery trailer was slowly winched towards the shore.

First the tail fin and then the bulk of Bluebird

herself cleared the surface of the lake. At this point

a degree of apprehension ran through the watching

crowd. It was an especially poignant moment for those

who had been involved in the record attempt

thirty-four years earlier and for the few present who

had actually witnessed the disaster. Understandably

many Coniston people had decided to stay away.

Two days later Bluebird was load ed onto a lorry,

covered with a tarpaulin and by 4 pm the same day was

safely delivered to a factory building on Tyneside

where stabilisation and some degree of restoration was

to be carried out.

Since the salvage operation, the team returned to the

crash site several times to look for additional

sections of Bluebird. Inevitably, during one of these

visits, the body of Donald Campbell was located, a

short distance away from where the wreck had been

found. Gina Campbell, Donald's only daughter, had

especially requested then to look out for him.

"Find my dad" she had asked, "I want to

put him somewhere warm".

Soon after the body was located it was recovered with

great dignity and with the full co-operation of the

coroner and police. A casket was lowered onto the lake

bed and the remains were placed in it. On Bank Holiday

Monday the casket was lifted onto the team's boat and

covered with the union flag. It was then brought to

Pier Cottage. While still out on the lake a short

impromptu service was carried out by the salvage team

as they waited for the coroner to arrive.

News of the location and recovery of the body again

shattered the village. However most people quickly

came round to the opinion that, whereas recovery of

the boat was questionable, recovery of the body was a

legitimate act which would allow a proper burial to

take place in Coniston at a later date.

There was one final act of recovery that was carried

out by the team. Gina Campbell was aware that her

father would have been wearing a small gold medallion

round his neck during the record attempt. It had been

given to him many years earlier by his father. The

team was asked to see if they could find it. The

outcome of this is best left to the writings of Bill

Smith, on the project web site:

Donald

Campbells body

On

the 28th May 2001 A body was recoverd from Coniston

Water by the Bluebird Project Team. Gina

Campbell,

Donalds Daughter asked if the team could locate and

recover her fathers body. There seems no doubt that

the body is that of Donald Campbell. DNA tests are

being carried out to confirm this.

The team recovered from the body a St Christopher,

which Sir Malcolm gave to Donald, and which has now

been passed on to Gina.

Body

in lake is Campbell Friday,

10 August, 2001

A

coroner has confirmed that human remains found in

Coniston Water are those of powerboating legend Donald

Campbell. An inquest heard tests on DNA samples

taken from the body and from members of Campbell's

family proved the remains were 1.9 million times more

likely to be those of the speed hero's than anyone

else.

Campbell

was trying to break his own water speed record of

276mph when his boat somersaulted before crashing.

Divers found the remains in May - 34 years after

Campbell's attempt ended in his death. Furness

coroner Ian Smith said there was "absolutely no

doubt" the body was that of Donald Campbell.

After the hearing in Barrow Town Hall, Cumbria,

Campbell's daughter Gina, 51, said she felt

"totally relieved". She said:

"There was always a little bit of doubt. Now

there is no doubt.

"The

mystery of the lake now becomes a reality."

Anthony

Hopkins plays Donald Campbell

Donald

Campbell CBE

23

March 1921 - 4 January 1967

"Of

records and record breakers, I would remind you that speed

is relative to time. What we consider slow now, was

unthinkable in years gone by. However, each time a

contender goes out onto the field of battle, he or she faces

the same hurdles, the same fears and financial challenges as

those before us, and most importantly of all, has to muster

themselves to boiling point make it all happen. In the

end, players will either triumph or fail, but in doing so,

show others where to, and where not to tread. All too

often players pay the ultimate price. Whether they

raise Man's technical mastery up another notch or not,

history should remember every last one of them - for they

were players." (Nelson

Kruschandl December 2005)

Nelson

Kruschandl

LINKS

:

Hydroplanes

and Racing:

Hydrofest

Hyrdroplane

& Raceboat Musuem

World

Water Speed Records

Hydros

Seattle

Outboard Association

|