|

AMERICAS CUP

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

History on the high seas - America's Cup is yachting's premier event

The America's Cup has it all, in a long and distinguished history. The oldest trophy in sport, an incredible scope of technological innovation, legendary figures from the world of sailing and international rivalry across the globe.

For 132 years that rivalry was dominated by the United States. America's run of success from 1851 is the longest in sport and their hold on the "Auld Mug" was total. Their dominance on the high seas was rarely seriously challenged until 1983 when Australia finally broke the stranglehold. New Zealand have since followed the lead of their Antipodean neighbours in becoming only the third country to hold the Cup following their victory in 1995. And their successful defence in 2000 came in the only America's Cup meeting never to feature the United States.

The America's Cup is the most famous trophy in the sport of yachting, and the oldest active trophy in sports. The cup, a silver ewer, is awarded to the winner of a match of up to nine races between two yachts from different countries, one representing the yacht club which holds the Cup and the other boat fielded by a yacht club challenging for the trophy. The race originated on August 22, 1851 when the 30.86 m schooner-yacht America owned by a syndicate representing the New York Yacht Club raced 15 yachts representing the Royal Yacht Squadron around the Isle of Wight. America won by 20 minutes. The syndicate which owned the America later donated the Cup through a Deed of Gift to the New York Yacht Club. The trophy would held in trust as a 'challenge' trophy to promote friendly competition between nations.

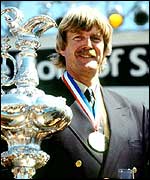

The America's Cup Silver Trophy

Stung by this blow to contemporary perception of invincible British sea power, a succession of British syndicates attempted to win back the cup. The New York Yacht Club remained unbeaten for 25 challenges over 132 years, the longest winning streak in the history of sport. The matches were held in the vicinity of New York Harbor until 1930, then sailed off Newport, Rhode Island for the rest of the NYYC's reign.

One of the most famous and determined challengers was Irish tea baron Sir Thomas Lipton, who mounted five challenges between 1899 and 1930, all in yachts named Shamrock. One of Lipton's motivations for making so many challenges was the publicity that the racing generated for his Lipton Tea company, though his original entry was at the personal request of the Prince of Wales in hopes of repairing trans-Atlantic ill-will generated by a contentious earlier challenger. Lipton was preparing for his sixth challenge when he died in 1931. The yachts from this era were huge by today's standards, with few restrictions.

After the Second World War, the 12 metre class of yachts were introduced. The NYYC's unbeaten streak continued in eight more defences, running from 1958 to 1980. Alan Bond, a flamboyant and at times dishonest Australian businessman made three challenges for the cup between 1974 and 1980. He returned in 1983 with a golden spanner which he claimed would be used to unbolt the cup from its plinth, so he could take it home.

In 1983 there were six foreign challenging syndicates for the cup. In order to establish who would be the actual "challenger", a series of elimination races were held, the prize for which was the Louis Vuitton Cup. In the challenger series, the Bond syndicate won easily. Then with the yacht Australia II representing the Perth Yacht Club, designed by Ben Lexcen and skippered by John Bertrand, the Australian syndicate won the America's Cup in a seven-race match 4-3 to break the 132-year winning streak.

Beaten skipper Dennis Conner won the cup back four years later, with the yacht Stars & Stripes representing the San Diego Yacht Club, but had to fend off an unprecedented 13 challenger syndicates to do it. Bond's syndicate lost the Defender series and did not race in the final. Technology was now playing an increasing role in the yacht design. The 1983 winner, Australia II, had sported an innovative but controversial "winged" keel, and the New Zealand boat Conner had beaten in the Louis Vuitton final in Fremantle was the first 12-metre to have a fibreglass hull construction rather than aluminium. The New Zealand syndicate had to fight off legal challenges from Conner's team who were demanding that 'core samples' be taken from the plastic hull (requiring the drilling of holes in the yacht hull) to prove that it met class specifications.

Then in 1988 a New Zealand syndicate, led by merchant banker Michael Fay, lodged a surprise "big boat" challenge that attempted to return to the original rules of the cup trust deed. Not wanting to be beaten, Conner's syndicate produced a new Stars and Stripes, a catamaran, which totally outclassed the challenger. The conflict descended into a bitter court room battle that ultimately confirmed that San Diego Yacht Club held the cup.

In the wake of the 1988 challenge, the International America's Cup Class (IACC) of yachts was introduced. These replaced the 12-meter class that had been used since 1958. First raced in 1992, the IACC yachts are the ones used today.

PETER BLAKE

Widely acknowledged as one of the greatest sailors of all time, Blake became a national hero in New Zealand when he secured the country's first-ever America's Cup success in 1995.

He went on to successfully defend the cup in 2000, making Team NZ the first non-American syndicate to achieve the feat. Blake then turned from competition to oceanic environmentalism, forming Blakexpeditions to carry out his work.

And in 2001, he was appointed a special envoy of the United Nations Environment Programme. It was during a trip to South America to measure the effects of global warming on one of the most environmentally sensitive regions of the world that Blake was killed. Blake's love of the sea was nurtured during a highly successful racing career. He won classics like the Jules Verne, the Fastnet Race, the Sydney-Hobart, and the Whitbread Round the World Race.

Blake celebrates his 1995 America's Cup success

But it was his America's Cup successes that brought him global fame. In 1995, Blake was the mainsail trimmer, as well as the head of the Team New Zealand syndicate, and his lucky red socks became a national symbol. The Kiwis won every race bar one - the only one Blake did not take part in - on their way to beating the USA 5-0 in the final. And sales of red socks went through the roof - before that final, the team's sponsors sold 100,000 pairs.

When Team NZ returned from the US with the Cup, hundreds of thousands of people turned out in Christchurch, Wellington and Auckland to welcome them home.

Missing giant

Five years later, Blake cemented his place in yachting history as New Zealand became the only country apart from the USA to successfully defend the Auld Mug. Following that success, Blake handed over the reins to Tom Schnackenberg, and his successor's words illustrate the esteem in which he was held. "Such a shock and such a waste of an important life," said Schnackenberg after Blake's murder. The sentiment was echoed all around the world. And when racing begins in the Hauraki Gulf in October, the sailors and spectators will feel the absence of a true giant of the seas.

The 2002-2003 Louis Vuitton Cup, held off Auckland, New Zealand saw nine teams from six countries staging 120 races over five months to select a challenger for the America's Cup.

On January 19, 2003 the Swiss challenger Ernesto Bertarelliís Alinghi, skippered by Russell Coutts, won the Louis Vuitton Cup Finals by defeating the American challenger, Larry Ellisonís Oracle BMW Racing, 4 - 1. Interestingly, Switzerland is a landlocked country.

On February 15, 2003, racing for the cup itself began. In a stiff breeze, Alinghi won the first race easily after New Zealand, skippered throughout the series by Dean Barker, withdrew due to multiple gear failures in the rigging and the low cockpit unexpectedly taking onboard large quantities of water. Race 2, on February 16, 2003, was won by Alinghi by a margin of only seven seconds. It was one of the closest, most exciting races seen for years, with the lead changing several times and a duel of 33 tacking manoeuvres on the fifth leg.

Then on February 18, in Race 3, Alinghi won the critical start, after receiving last minute advice about a wind shift, and led throughout the race, winning with a 23 second margin. After nine days without being able to race, first due to a lack of wind, then with high winds and rough seas making it too dangerous to race, February 28, originally a planned lay-day, was chosen as a race day.

Rough seas: OneWorld have had a point docked

Race 4 was again sailed in strong winds and rough seas and New Zealand's difficulties continued, when her mast snapped on the third leg. The next day, March 1, 2003, was again a frustratingly calm day, with racing called off after the yachts had again spent over two hours waiting for a start in the light air. Alinghi skipper Russell Coutts was unable to celebrate his 41st birthday with a cup win, but was in a commanding position in the series to do so on March 2. Race 5 started on time in a good breeze. Alinghi again won the start and kept ahead. On the third leg, New Zealand broke a spinnaker pole during a manoeuvre. Although it was put overboard and replaced with a spare pole, New Zealand was unable to recover, losing the race and the cup.

The win by Alinghi meant Coutts, who had previously sailed for New Zealand, had won every one of the last 14 America's Cup races he had competed in as skipper, the most by any America's Cup skipper. This meant he had won an America's Cup regatta twice as challenger as well as having been a successful defender. Coutts was not the only New Zealander to be sailing for foreign syndicates in the 2002-2003 regatta. Alinghi alone had four New Zealanders as crew. Chris Dickson, skipper of Oracle BMW, also a New Zealander, had been involved in a previous New Zealand challenge for the America's Cup. Whatever the outcome of both the Louis Vuitton Cup and the America's Cup, it was certain that the winning skipper would be a New Zealander from the first race of the Louis Vuitton Cup final.

The Alinghi team will defend the America's Cup in 2007, according to announcements made following their victory. It was announced on November 27, 2003 that the venue would be Valencia, Spain. This will be the first time that the America's Cup will be held in Europe in over 150 years. They are planning to have several events leading up to the Cup races, which they will call "Act I" (September, 2004, Marseille, France), "Act 2" (October, 2004, Valencia, Spain), "Act 3" (October, 2004, Valencia, Spain), and other "Acts", yet to be finalized. These events will feature fleet and match racing between America's Cup class yachts representing the syndicates that will by vying for the Cup in 2007. The deadline to challenge for the 32nd America's Cup is April 29th, 2005.

The schedule for the Acts in 2005 includes events in Valencia (June 16-26), Malmo-Skane, Sweden (August 25-September 4) and Trapani, Italy (September 29-October 9).

America's Cup winners and challengers - RESULTS

America will be looking to redress the balance of power in 2003 in a set of races that will determine whether the tide has turned in yachting's premier event for good. The series of races, that now runs to 31, started when John Cox Stevens, first commodore and founder of the New York Yacht Club, travelled across the Atlantic to prove American shipbuilding skills.

His boat, America, beat a British fleet in the Royal Victoria Yacht Club Regatta around the Isle of Wight and with it won the 100 Guinea Cup. It has been known as the America's Cup ever since, in honour of the first winning boat. In that time the contest has undergone a number of changes, most significantly among the yachts that take part.

By their third defence the hosts had agreed to race one against one and the change was the catalyst for the craft development for which the contest has become renowned. America's Cup yachts, be they schooners, 90-footers, J-boats, 12-metre boats or the present International America's Cup Class, have always been at the pinnacle of sailing technology.

Blake celebrates New Zealand's 1995 win

And America's Cup history reveals a rich tapestry of famous names. Men such as Harold S Vanderbilt and Sir Thomas Lipton have ploughed funds into both winning and losing efforts. Today the Cup has become big business and syndicates now put anything into the region of £100m to fund attempts.

But wealth alone does not win yachting's most prestigious trophy. Although the weight of financial support is important, boat design and tactical acumen are key. With designers such as the former professor of entomology Edward Burgess, the legendary Nathanial Herreshoff and Olin Stephens, America invariably held the upper hand.

Skippers such as Charles J Paine, Charlie Barr, Vanderbilt, Emil "Bus" Mosbacher, Ted Turner, Bill Ficker, Dennis Conner and Bill Koch were then on hand to get the best out of each boat and their crew. Conner is the only four-time skipper in Cup history and became the first American to lose the title in 1983. Australia's revolutionary winged-keel design was a key component of that defeat.

And when New Zealand became only the second country outside America to lay claim to the Cup in 1995 it was the tactics and experience of their crew that proved vital. With limited funding, the late Sir Peter Blake, lucky red socks and all, put the seal on one of the most remarkable chapters in the sport.

New Zealand have since built on that victory and are forging their own place in the history of the event. America will be out to stop them in their tracks, but must first contend with the Louis Vuitton Cup series that was set up in 1983 to determine the challenger. American pride means they will be hell bent on winning through to contend for a piece of silverware they once considered their own. Whether or not they can break New Zealand's grip on the America's Cup promises to add to the tradition and excitement of one of the world's premier sporting events.

Blake

casts long shadow

Hosts

enter history books

The

early years

The

turn of the century

The

inter-war years

The

rebirth

The

modern era

America's

Cup results

When the Cup runs over - Wednesday 25 September 2002

If

America's Cup history has taught us one thing, it is

that few campaigns pass by without controversy.

In the

heat of the quest for the prized Auld Mug, tensions

mount and something can be relied on to cast a shadow

of suspicion over proceedings.

From law suits and blazing wars of words to scuba-diving spies, the America's Cup has seen it all, and the 2002/03 instalment promises yet more intrigue. Before racing even started, US challenger OneWorld was penalised for holding design secrets belonging to rival syndicates Team New Zealand and Prada.

And the whole event was jeopardised at one stage, when sources close to the Cup's arbitration committee revealed that a fear of being sued was making it impossible for the arbiters to do their job properly. That concern appears to have been allayed for now.

But allegations of foul play will rumble on and the race jurors are sure to be kept busy with all manner of appeals. Some of these could make incredible headlines.

In 1983 - the year Australia became the first country to beat the USA - a huge argument brewed between challenger and holder over Australia II's "secret keel". The infamous keel used to be covered up at night to protect it from prying eyes, but one evening, guards chased away skin-divers who tried to sneak a look.

Australia charged the New York Yacht Club with illegal espionage and the NYYC countered by asking the International Yacht Racing Union to disqualify its foe for having an illegal design. The race went on, and it turned out that Australia II - the smallest boat ever to compete for the America's Cup - did have an extra-heavy keel, fitted with fins. But this was not outlawed and the challengers went on to win a narrow series 4-3. Acrimony between the USA and Australia dates back to 1967. In that year, their representative yachts collided shortly after the start of a race the Australia craft went on to win.

Alan Bond's bid was shrouded in secrecy

It

was disqualified, which prompted a flood of

complaints, including one from a furious Australian MP

who demanded that his country withdraw its US

ambassador. And the Americans have also rubbed

up current hosts New Zealand along the way. In

1988, Team Dennis Conner answered a Kiwi challenge

with a giant catamaran and the event descended into a

succession of court battles.

An eventual ruling found in favour of the successful US syndicate, but the controversy led to the standardisation of boats under America's Cup Class specifications, which are still in effect today. England

has courted its share of controversy too. Way

back in 1895, the Earl of Dunraven's challenger

Valkyrie III apparently won the second race of a

series, but was also disqualified. Dunraven

protested so loudly that he was stripped of his

honorary NYYC membership. As a direct result,

England did not challenge again until 1934, when

another technical decision prompted one disillusioned

British writer to declare:

"Britannia rules the waves, but America waives the rules." His words speak volumes about the passion and pride caught up in any America's Cup campaign. Sportsmanship and skill should shine through in the Hauraki Gulf, but no-one should be surprised if tempers flare at dockside from time to time. And no-one should complain either. Within limits, controversy and scandal have their own place in the world's premier sailing event

MORE LINKS:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2019. All rights reserved. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity.

|