|

AZTECS

|

||||

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | BOOKS | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | INVESTORS | MUSIC | NEWS | SOLAR BOATS | SPORT |

||||

|

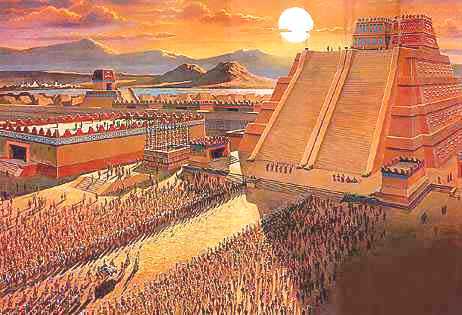

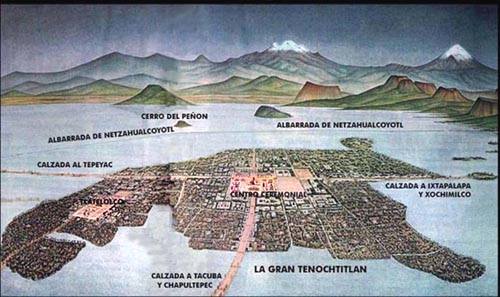

The Aztecs, or more properly, the Mexicas, for whom the later Republic of Mexico was named, were a Mesoamerican people of central Mexico in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. They were a civilization with a rich mythology and cultural heritage. Their capital was Tenochtitlan, built on raised islets in Lake Texcoco – the site of modern-day Mexico City. The Aztec empire produced the biggest demographic explosion in Mesoamerica: the population grew from an estimated 10 million to 15 million.

Aztec warrior

Nomenclature

Aztec is usually used as a historical term, although some contemporary Nahuatl-speakers would consider themselves Aztecs. More particularly, the term refers to the empire of the Mexicas as distinguished from the Mexicas alone. This article deals with the historical Aztec civilization, not with modern-day Nahuatl speakers.

In Nahuatl, the native language of the Mexicas, Azteca means "someone who comes from Aztlán", a mythical place commonly believed to be located in northern Mexico or the Southwest U.S. (though there is great doubt about this, see current debates in Mexica scholarship), so this name was applied to other cultures of the same cultural group. However, the culture we call now Aztec referred to themselves as Mexica (IPA: [meihkah]) or Tenochca and Tlatelolca according their city of origin. Their use of the word azteca was like the modern use of Latino, or Mediterranean: a broad term that does not refer to a specific culture.

Alexander von Humboldt originated the modern usage of Aztec as a collective term applied to all the people linked by trade, custom, religion , and language to the Mexica state, the Triple Alliance. The term was adopted by Mexican scholars of 19th century, as a way to distance "modern" Mexicans from pre-conquest Mexicans. This has become controversial in more recent years, and consequently, the more proper usage "Mexica" is increasingly applied.

Mexica, the origin of the word Mexico, is a term of uncertain origin. Very different etymologies are proposed: the old Nahuatl word for the sun, the name of their leader Mexitli, a type of weed that grows in Lake Texcoco. The most renowned Nahuatl translator, Miguel León-Portilla, suggests that it means "navel of the moon" from Nahuatl metztli (moon) and xictli (navel) or, alternatively, it could mean navel of the maguey (Nahuatl metl).

Aztec pyramid

Government

The Aztec Empire is not completely analogous to the empires of European history. Like most European empires, it was ethnically very diverse, but unlike most European empires, it was more a system of tribute than a single system of government. Arnold Toynbee in War and Civilization analogizes it to the Assyrian Empire in this respect.

Although cities under Aztec rule seem to have paid heavy tributes, excavations in the Aztec-ruled provinces show a steady increase in the welfare of common people after they were conquered. This probably was due to an increase of trade, thanks to better roads and communications, and the tributes were extracted from a broad base. Only the upper classes seem to have suffered economically, and only at first. There appears to have been trade even in things that could be produced locally: love of novelty may have been a factor. There was even trade with cities considered enemies. The Purepechas, the only people who defeated the Aztecs, were the main source of copper axes.

The main contribution of the Aztec rule was a system of communications between the conquered cities. In Mesoamerica, they had no animals for transport, nor wheeled vehicles, so the roads were designed for travel on foot. Usually these roads were part of the tributes, and travelers had places to rest, eat, and even latrines at regular intervals, every 10 or 15 km. They were constantly watched, so even women could travel alone. Also, couriers (Paynani) were constantly traveling along those ways, keeping the Aztecs informed of events.

The most important official of Tenochtitlan government was often called The Aztec Emperor. The Nahuatl title, Huey Tlatoani (plural huey tlatoque), translates roughly as "Great Speaker"; the tlatoque ("speakers") were an upper class. This office gradually took on more power with the rise of Tenochtitlan. By the time of Auitzotl "Emperor" is an appropriate analogy, although as in the Holy Roman Empire, the title was not hereditary.

Coat of Arms of Mexico, from Aztec mythology

Religion

The main deity in the Mexica religion was their sun god and war god, Huitzilopochtli. He directed the Mexicas to found a city on the site where they would see an eagle, in some accounts devouring a snake, perched on a fruit bearing nopal cactus. The Mexicas built their city of Tenochtitlan on that site, on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco, modern-day Mexico City. This legendary vision is pictured on the Coat of Arms of Mexico.

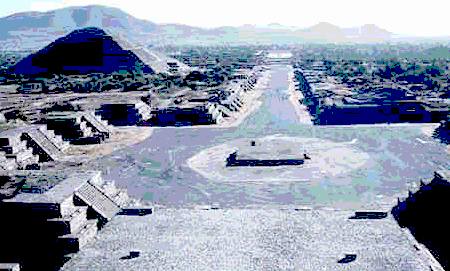

According to legend, when the Mexicas arrived in the Anahuac valley around Lake Texcoco, they were considered by the other groups as the least civilized of all. The Mexicas decided to learn, and they took all they could from other peoples, especially from the ancient Toltec (whom they seem to have partially confused with the more ancient civilization of Teotihuacan). To the Mexicas, the Toltecs were the originators of all culture; "Toltecayotl" was a synonym for culture. Mexica legends identify the Toltecs and the cult of Quetzalcoatl with the mythical city of Tollan, which they also identified with the more ancient Teotihuacan.

Another important god of the Mexica pantheon was Tlaloc, the rain god of all the Nahuatl-speaking peoples. This god was elevated to co-equal status with Huitzilipochtli, as evidenced by the twin pyramids uncovered near the Zocalo in Mexico City in the late 1970s.

Another significant Mexica deity was the earth mother goddess Tonantzin. It was her shrine in the northern section of today's Mexico City which was later transformed into the Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, a central icon in Mexican Catholic belief.

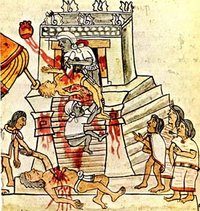

Human sacrifice

For millennia the practice of human sacrifice was widespread in Mesoamerican and South American cultures. It was a theme in the Olmec religion, which thrived between 1200 BC and 400 BC. Later the Inca and Maya also made human sacrifices, but the Aztecs practiced it on a particularly large scale.

For the reconsecration of Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, the Aztecs reported that they sacrificed about 84,400 prisoners over the course of four days, This would mean almost 15 per minute for 24 hours a day. Tenochtitlan itself had an estimated population of 80,000 to 120,000 in that time, with as many as 700,000 in the cities immediately surrounding Lake Texcoco. Since the Aztecs reported the number of sacrifices themselves, they could have inflated the number as a propaganda tool especially if, as reported, Ahuitzotl sacrificed them personally.

Aztec sacrifice

The Structure of Aztec Society

Class structure

The society traditionally was divided into two social classes; the macehualli (people) or peasantry and the pilli or nobility. Nobility was not originally hereditary, although the sons of pillis had access to better resources and education, so it was easier for them to become pillis. Eventually, this class system took on the aspects of a hereditary system. The Aztec military had an equivalent to military service with a core of professional warriors; only those that had taken prisoners could become full-time warriors, and eventually the honors and spoils of war would make them pillis. Once an Aztec warrior had captured 4 or 5 captives, he would be called tequiua and could attain a rank of Eagle or Jaguar knight, sometimes translated as "captain", eventually he could reach the rank of tlacateccatl or tlachochcalli. To be elected as tlatoani, one was required to have taken about 17 captives in war. When Aztec boys attained adult age, they stopped cutting their hair until they took their first captive; sometimes two or three youths united to get their first captive; then they would be called iyac. If after a certain time, usually three combats, they could not gain a captive, they became macehualli; their hair would still be quite long, indicating that they had not gotten a captive yet. That was rather shameful.

The abundance of tributes led to the emergence and rise of a third class that was not part of the traditional Aztec society: pochtecas or traders. Their activities were not only commercial: they also were an effective intelligence gathering force. They were scorned by the warriors - who nonetheless sent to them their spoils of war in exchange for blankets, feathers, slaves, and other presents.

In the later days of the empire, the concept of macehualli also had changed. Eduardo Noguera (Annals of Anthropology, UNAM, Vol. xi, 1974, p. 56) estimates only 20% of the population was dedicated to agriculture and food production. The chinampa system of food production was very efficient; it could provide food for about 190,000 people. Also, a significant amount of food was obtained by trade and tribute. The Aztec were not only conquering warriors, but also skilled artisans and aggressive traders. Eventually, most of the macehuallis were dedicated to arts and crafts. Their works were an important source of income for the city (Sanders, William T., Settlement Patterns in Central Mexico. Handbook of Middle American Indians, 1971, vol. 3, p. 3-44).

Excavations of some cities under Aztec rule show that a sizeable number of luxury items were produced in Tenochtitlan. More excavations are needed to show if this was true in other Aztec provinces, but if trade was as important as it seems, this could explain the rise of the Pochteca as a powerful class.

Aztec pyramid Cholula

Slavery

Slaves or tlacotin (distinct from war captives) also constituted an important class. This slavery was very different from what Europeans of the same period were to establish in their colonies, although it had much in common with the slaves of classical antiquity. (Sahagún doubts the appropriateness even of the term "slavery" for this Aztec institution.) First, slavery was personal, not hereditary: a slave's children were free. A slave could have possessions and even own other slaves. Slaves could buy their liberty, and slaves could be set free if they were able to show they had been mistreated or if they had children with or were married to their masters.

Typically, upon the death of the master, slaves who had performed outstanding services were freed. The rest of the slaves were passed on as part of an inheritance.

Another rather remarkable method for a slave to recover liberty was described by Manuel Orozco y Berra in La civilización azteca (1860): if, at the tianquiztli (marketplace; the word has survived into modern-day Spanish as "tianguis"), a slave could escape the vigilance of his or her master, run outside the walls of the market and step on a piece of human excrement, he could then present his case to the judges, who would free him. He or she would then be washed, provided with new clothes (so that he or she would not be wearing clothes belonging to the master), and declared free. Because, in stark contrast to the European colonies, a person could be declared a slave if he or she attempted to prevent the escape of a slave (unless that person were a relative of the master), others would not typically help the master in preventing the slave's escape.

Orozco y Berra also reports that a master could not sell a slave without the slave's consent, unless the slave had been classified as incorrigible by an authority. (Incorrigibility could be determined on the basis of repeated laziness, attempts to run away, or general bad conduct.) Incorrigible slaves were made to wear a wooden collar, affixed by rings at the back. The collar was not merely a symbol of bad conduct: it was designed to make it harder to run away through a crowd or through narrow spaces.

When buying a collared slave, one was informed of how many times that slave had been sold. A slave who was sold four times as incorrigible could be sold to be sacrificed; those slaves commanded a premium in price.

However, if a collared slave managed to present him- or herself in the royal palace or in a temple, he or she would regain liberty.

An Aztec could become a slave as a punishment. A murderer sentenced to death could instead, upon the request of the wife of his victim, be given to her as a slave. A father could sell his son into slavery if the son was declared incorrigible by an authority. Those who did not pay their debts could also be sold as slaves.

People could sell themselves as slaves. They could stay free long enough to enjoy the price of their liberty, about twenty blankets, usually enough for a year; after that time they went to their new master. Usually this was the destiny of gamblers and of old ahuini (courtesans or prostitutes).

Motolinía reports that some captives, future victims of sacrifice, were treated as slaves with all the rights of an Aztec slave until the time of their sacrifice, but it is not clear how they were kept from running away..

Aztec pyramid of the sun

Daily Life

Diet

The Aztec created artificial islands or chinampas on Lake Texcoco, on which they cultivated crops. The Aztec staple foods included maize, beans and squash. Chinampas were a very efficient system and could provide up to seven crops a year, on the basis of current chinampa yields, it has been estimated that 1 hectare of chinampa would feed 20 individuals, with about 9,000 hectares of chinampa, there was food for 180,000 people.

Much has been said about a lack of proteins in the Aztec diet, to support the arguments on the existence of cannibalism (M. Harner, Am. Ethnol. 4, 117 (1977)), but there is little evidence to support it: a combination of maize and beans provides the full quota of essential amino acids, so there is no need for animal proteins. The Aztecs had a great diversity of maize strains, with a wide range of amino acid content; also, they cultivated amaranth for its seeds, which have a high protein content.

They cultivated chia, also high in protein. More important is that they had a wider variety of foods. Chilis and tomatoes, prominent to this day, were cultivated. They harvested acocils, a small and abundant shrimp of Lake Texcoco, also spirulina algae, which was made into a sort of cake that was rich in flavonoids, and they ate insects, such as crickets (chapulines), maguey worms, ants, larvae, etc. Insects have a higher protein content than meat, and even now they are considered a delicacy in some parts of Mexico. Aztecs also had domestic animals, like turkey and some dog breeds that provided meat, although usually this was reserved for special occasions. Hunting was also another source of meat—deer, wild hogs, ducks etc.

A study by Montellano (Medicina, nutrición y salud aztecas, 1997) shows a mean life of 37 (±3) years for the population of Mesoamerica.

Aztecs also used maguey extensively; from it they obtained food, sugar (aguamiel–honey water), drink (pulque), and fibers for ropes and clothing. Use of cotton and jewelry were restricted to the elite. They also kept beehives and harvested honey. Cocoa grains were used as money but also to make a chocolate drink much like beer. Subjugated cities paid annual tribute in form of luxury goods like feathers and adorned suits.

After the Spanish conquest some foods were outlawed, particularly amaranth because of its central role in religious belief, and there was less diversity of food. This led to chronic malnutrition in the general population.

Recreation

Although one could drink pulque, a fermented beverage with an alcoholic content equivalent to beer, getting drunk before the age of 60 was forbidden. While the first time was punished, repeat incidents could be punished by death.

Like in modern Mexico, the Aztecs had strong passions over a ball game, but this in their case it was tlachtli, the Aztec variant of the ulama game, the ancient ball game of Mesoamerica. The game was played with a ball of solid rubber, about the size of a human head. The ball was called "olli", whence derives the Spanish word for rubber, "hule". The city had two special buildings for the ball games. The players hit the ball with their hips, knees, and elbows.

They had to pass the ball through a stone ring to automatically win. This was difficult, so they could hit markers on the walls to earn points.The fortunate player that could do this had the right to take the blankets of the public, so his victory was followed by general running of the public, with screams and laughter. People used to bet on the results of the game. Poor people could bet their food, pillis could bet their fortunes, tecutlis (lords) could bet their concubines or even their cities, and those who had nothing could bet their freedom and risk becoming slaves.

The Aztecs also enjoyed board games, like "Patolli" and "Totoloque". Bernal Diaz coments how Cortés and Moctezuma II played totoloque. Arts

Song and poetry were highly regarded; there were presentations and poetry contests at most of the Aztec festivals. Also there was a kind of dramatic presentation that included players, musicians and acrobats.

Poetry was the only occupation worthy of an Aztec warrior in times of peace. A remarkable amount of this poetry survives, having been collected during the era of the conquest. In some cases, we know names of individual authors, such as Netzahualcoyotl, Tolatonai of Texcoco, and Cuacuatzin, Lord of Tepechpan. Miguel León-Portilla, the most renowned translator of Nahuatl, comments that it is in this poetry where we can find the real thought of the Aztecs, independent of "official" Aztec ideology.

In the basement of the Great Temple there was the "house of the eagles", where in peacetime Aztec captains could drink a foaming chocolate, smoke good cigars, and have poetry contests. The poetry was accompanied by percussion instruments (teponaztli). Recurring themes in this poetry are whether life is real or a dream, whether there is an afterlife, and whether we can approach the giver of life.

The Aztec people also enjoyed a type of dramatic presentation, although it could not be called theater. Some were comical with music and acrobats, others were staged dramas of their gods. After the conquest, the first Christian churches had open chapels reserved for these kinds of representations. Plays in Nahuatl, written by converted Indians, were an important instrument for the conversion to Christianity, and are still found today in the form of traditional pastorelas, which are played during Christmas to show the Adoration of Baby Jesus, and other Biblical passages.

México-Tenochtitlan

Education

Until the age of fourteen, the education of children was in the hands of their parents, but supervised by the authorities of their calpulli. Periodically they attended their local temples, to test their progress.

Part of their education was a collection of sayings, called huehuetlatolli ("The sayings of the old"), that represented the Aztecs' ideals. It included speeches and sayings for every occasion, the words to salute the birth of children, and to say farewell at death. Fathers admonished their daughters to be very clean, but not to use makeup, because they would look like ahuianis. Mothers admonished their daughters to support their husbands, even if they turn out to be humble peasants. Boys were admonished to be humble, obedient and hard workers.

Boys and girls went to school at age 15. Probably this was one of the first societies that required education for all its members, without regard of sex or social status. There were two types of educational institutions. The telpochcalli or House of the Young, taught history, religion, military fighting arts, and a trade or craft (such as agriculture or handicrafts). Some of the telpochcalli students were chosen for the army, but most of them returned to their homes. The calmecac, attended mostly by the sons of pillis, was focused on turning out leaders (tlatoque), priests, scholars/teachers (tlatimini), healers (tizitl) and codex painters (tlacuilos). They studied rituals, ancient and contemporary history, literacy, calendrics, some elements of geometry, songs (poetry), and, as at the telpochcalli, military arts.

Each Calpulli was specialized in some handicrafts, and this was an important part of the income of the city. So the teaching of handicraft was very apreciated.

Also, the healers or Tizitl had several specialities. Some were trained to just look and classify medicinal plants, others were training just in the preparation of medicines that were sold in special places (Tlapalli), more than a hundred preparations are known, including deodorants, remedies for smelly feet, dentifric paste etc. Also there were Tizitl specialized in surgery, digestive disease, teeth and nose, skin diseases etc.

Aztec teachers or Tlatimine, propounded a spartan regime of education – cold baths in the morning, hard work, physical punishment, bleeding with maguey thorns and endurance tests – with the purpose of forming a stoical people.

There is contradictory information about whether calmecac was reserved for the sons and daughters of the pillis; some accounts said they could choose where to study. It is possible that the common people preferred the telpochcalli, because a warrior could advance more readily by his military abilities; becoming a priest or a tlacuilo was not a way to rise rapidly from a low station.

Girls were educated in the crafts of home and child raising. They were not taught to read or write. Some of them were educated as midwives and received the full training of a healer and they were called also Tizitl. All women were taught to be involved "in the things of god", there are paintings of women presiding over religious ceremonies, but there are no references to female priests.

There were also two other opportunities for those few who had talent. Some were chosen for the house of song and dance, and others were chosen for the ball game. Both occupations had high status.

Tenochtitlan

Tenochitlan was the capital city of the Aztec empire, and the site of modern-day Mexico City. Aztec priests received a vision of the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli, who told them to settle where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus full of fruits (Tenoctli), and eating bird of precious feathers (Florentine Codex). The priests found this place on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. Modern historians, estimate of the peak population of Tenochtitlan to be between 60,000 to 130,000 inhabitants at its peak, surpassed in population only by Constantinople with about 200,000 inhabitants, Paris with about 250,000, and Venice with about 160,000.

Antropologist Eduardo Noguera, estimates the population at 200,000 based in the house count and merging the population of Tlatelolco (once an independent city, but later became a suburb of Tenochtitlan). If one includes the surrounding islets and shores surrounding Lake Texcoco, estimates range from 300,000 to 700,000 inhabitants.

The city had very good symmetry. It was divided in four city sections called campan, each "campan" was divided in 20 towns called "calpulli". Three wide avenues cross the city from one side to the other, these avenues were extended to firm ground. The "calpullis" were divided by canals called "tlaxilcalli". There always was a wide street parallel to these canals. People cross "tlaxilcalli" using wood bridges that were removed at nights.

The canals were useful for transportation with rafts made with "totoras". There were rafts for collecting garbage and other ones to collect excrement that was used for fertilization at "chinampas" (aztec agriculture technology). About one-thousand people were employed for street cleaning. Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote about how he was surprised at finding latrines in homes, public markets and on the paths.

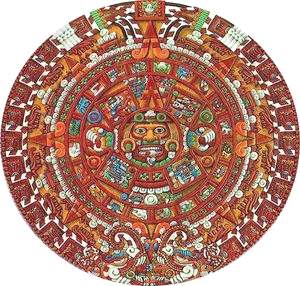

Aztec Sun Stone, often mistakenly called the Aztec Calendar Stone

HistoryRise of the Aztecs

There were twelve rulers or tlatoque (singular: tlatoani) of Tenochtitlan:

After the fall of Tula, in the 12th century, in the valley of Mexico and surroundings, there were several city states of Nahua-speaking people: Cholula, Huexotzingo, Tlaxcala, Atzcapotzalco, Chalco, Culhuacan, Xochimilco, Tlacopan, etc. No single one of them was powerful enough to dominate other cities, and they were somewhat united by a common Toltec background. Aztec chronicles describe this time as a golden age, when music was established, people learned arts and crafts from surviving Toltecs, and rulers held poetry contests in place of wars.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, around the Lake Texcoco in the Anahuac Valley, the most powerful of these city states were Culhuacan to the south, and Azcapotzalco to the west. Between them, they controlled the whole Lake Texcoco area.

As a result, when the Mexica arrived to the Anahuac valley as a semi-nomadic tribe, they had nowhere to go. They settled temporarily in Chapultepec, but this was under the rule of Azcapotzalco, the city of the "Tepaneca", and they were soon expelled. They then went to the area dominated by Culhuacan and, in 1299, the ruler Cocoxtli gave them permission to settle in the empty barrens of Tizapan. They assimilated to Culhuacan culture: they took and married Culhuacan women, so that those women could teach their children. In 1323, they asked the new ruler of Culhuacan, Achicometl, for his daughter, in order to make her the goddess Yaocihuatl. Unbeknowest to the king, the Mexica actually planned to sacrifice her. As the story goes, during a festival dinner, a priest came out wearing her flayed skin as part of the ritual. Upon seeing this, the king and the people of Culhuacan were horrified and expelled the Mexica. Forced to flee, in 1325 they went to a small islet in the center of the lake where they began to build their city "Mexico - Tenochtitlan", eventually creating a large artificial island. After a time, they elected their first tlatoani, Acamapichtli, following customs learned from the Culhuacan. Another Mexica group settled on the north shore: this would become the city of Tlatelolco. Originally, this was an independent Mexica kingdom, but eventually it was taken over by the Tenochca Mexica and treated as a "fifth" quadrent. The famous marketplace described by Cortés and Díaz was actually located in Tlatelolco.

During this period, the islet was under the jurisdiction of Azcapotzalco, and the Mexica had to pay heavy tributes to stay there.

Initially, the Mexica hired themselves out as mercenaries in wars between Nahuas, breaking the balance of power between city states. Eventually they gained enough glory to receive royal marriages. Mexica rulers Acamapichtli, Huitzilihuitl and Chimalpopoca were, in 1372–1427, vassals of Tezozomoc, a lord of the Tepanec nahua.

When Tezozomoc died, his son Maxtla assassinated Chimalpopoca, whose uncle Itzcoatl allied with the ex-ruler of Texcoco, Nezahualcoyotl, and besieged Maxtla's capital Azcapotzalco. Maxtla surrendered after 100 days and went into exile. The Triple Alliance

Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan formed a "Triple Alliance" that came to dominate the Valley of Mexico, and then extended its power beyond. Tenochtitlan gradually became the dominant power in the alliance.

Motecuhzoma I and his successors

Itzcoatl's nephew Motecuhzoma I inherited the throne in 1449 and expanded the realm. His son Axayacatl (1469) surrounding kingdom of Tlatelolco. His sister was married to the tlatoani of Tlatelolco, but, as a pretext for war, he declared that she was mistreated. He went on to conquer Matlazinca and the cities of Tollocan, Ocuillan, and Mallinalco. He was defeated by the Tarascans in Tzintzuntzan (the first great defeat the Aztecs had ever suffered), but recovered and took control of the Huasteca region, conquering the Mixtecs and Zapotecs.

In 1481 Axayacatl's son Tizoc ruled briefly, but he was considered weak, so he was replaced (possibly through assassination by poisoning) by his younger brother Ahuitzol who had reorganized the army. The empire was at its largest during his reign. His successor was Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (better known as Moctezuma II), who was tlatoani when the Spaniards arrived in 1519.

Tlacaelel

Most of the Aztec empire was forged by one man, Tlacaelel (Nahuatl for "manly heart"), who lived from 1397 to 1487. Although he was offered the opportunity to be tlatoani, he preferred to stay behind the throne. Nephew of Tlatoani Itzcoatl, and brother of Chimalpopoca and Motecuhzoma Ilhuicamina, his title was "Cihuacoatl" (in honor of the goddess, roughly equivalent to "counselor"), but as reported in the Ramírez Codex, "what Tlacaellel ordered, was as soon done". He gave the Aztec government a new structure, he ordered the burning of most Aztec books (his explanation being that they were full of lies) and he rewrote their history.

In addition, Tlacaelel reformed Aztec religion, by putting the tribal god Huitzilopochtli at the same level as the old Nahua gods Tlaloc, Tezcatlipoca, and Quetzalcoatl. Tlacaelel thus created a common awareness of history for the Aztecs. He also created the institution of ritual war (the flowery wars) as a way to have trained warriors, and created the necessity of constant sacrifices to keep the Sun moving.

Some writers believe upper classes were aware of this forgery, which would explain the later actions of Moctezuma when he met Hernán Cortés (a.k.a. Cortez). But eventually this institution helped to cause the fall of the Aztec empire. The people of Tlaxcala were spared conquest, at the price of participating in the flower wars. When Cortés came to know this, he approached them and they became his allies. The Tlaxcaltecas provided thousands of men to support the few hundred Spaniards. The Aztec strategy of war was based on the capture of prisoners by individual warriors, not on working as a group to kill the enemy in battle. By the time the Aztecs came to recognize what warfare meant in European terms, it was too late.

Great leaders

Fall of the Aztec Empire

The Aztecs were conquered by Spain in 1521, when after long battle and a long siege of the capital, Tenochtitlan, where much of the population died from hunger and smallpox, Cuauhtémoc surrendered to Hernán Cortés. Cortés, with his up to 500 Spaniards, did not fight alone but with as many as 150,000 or 200,000 allies from Tlaxcala, and eventually from Texcoco, who were resisting Aztec rule. He defeated Tenochtitlan's forces on August 13, 1521.

The fall of Tenochtitlan usually is referred to as the main episode in the process of the conquest, but this process was much more complex. It took almost 60 years of wars to conquest Mesoamerica (Chichimeca wars), a process that could have taken longer, but three separate epidemics took a heavy toll on the population. The impact of epidemics on the Aztec Empire

The first epidemic, an outbreak of smallpox (cocoliztli) occurred from 1520-1521 and decimated the population of Tenochtitlan and was decisive in the fall of the city.

The other two epidemics, of smallpox (1545-1548) and typhus (1576-1581) killed up to 75% of the population of Mesoamerica. The population before the time of the conquest is estimated at 15 million; by 1550, the estimated population was 4 million and less than two millions by 1581. Whole towns disappeared, lands were deserted, roads were closed and armies were destroyed. The "New Spain" of the XVI century was a depopulated country and many Mesoamerican cultures were wiped out. However, despite this, the indigenous people, even at their lowest demographic ebb, far outnumbered the Spanish colonials.

After the fall of Tenochtitlan

Even after the fall of Tenochtitlan, most of the other Mesoamerican cultures were intact. The Tlaxcaltecas expected to get their part; the Purepechas and Mixtecs probably were happy at the defeat of their longtime enemy, and it was the same for other cultures.

It seemed that the Cortés's intention was to maintain the structure of the Aztec empire, and at first it seemed the Aztec empire could survive. The upper classes at first were considered as noblemen (to this day, the title of Duke of Moctezuma is held by a Spanish noble family), they learned Spanish, and several learned to write in European characters. Some of their surviving writings are crucial in our knowledge of the Aztecs. Also, the first missionaries tried to learn Nahuatl and some, like Bernardino de Sahagún, decided to learn as much as they could of the Aztec culture.

But soon all changed. Eventually, the Indians were not only forbidden to learn of their cultures, but also were forbidden to learn to read and write in Spanish, and, under the law, they had the status of minors. An Aztec lament of the fall of Tenochtitlan

An anonymous Aztec poet wrote:

– From the Informantes Anónimos de Tlatelolco, compiled in 1521.

Legacy

Mexico City was built on the ruins of Tenochtitlan, making it one of the oldest living cities of America. Many of its districts and natural landmarks retain their original Nahuatl names. Many other cities and towns in Central Mexico were also originally Mexica towns, also often retaining their original Nahuatl names, or combining them with Spanish.

The modern Mexican flag bears the emblem of the Mexica's migration legend. The Mexica earth mother goddess Tonantzin lives on in the guise of Mexico's premier religious icon, the Virgen of Guadalupe.

Nahuatl is still spoken by Mexican Indians (who still claim Yo hablo mexicano – "I speak Mexican"), mostly in mountainous areas in the states surrounding Mexico City. Moreover, Nahuatl survives among the entire Mexican population, comprising a significant part of the Mexican Spanish dialect, some of which has even come into American English.

Mexican cuisine continues to be based on and flavored by agricultural products contributed by the Mexicas/Aztecs and MesoAmerica generally, most of which retain some form of their original Nahautl names. The cuisine has also become a popular part of the cuisine of the United States and other countries around the world, typically altered to suit various national tastes.

Many modern Mexicans, most of whom are of mixed Spanish and indigenous ancestry, are descendants of the Mexicas, and/or of the many other indigenous peoples of the Aztec Empire and beyond. Sources

There are only four Aztec codices made before the conquest, so most existing sources were written after the conquest. This has created problems with the trustworthiness of the writing. Each source has its problems.

Information about Aztecs survives in contemporary sources like Codex Mendoza made by aztec tlacuilos in 1541 under spanish authorities.

The accounts of the conquistadores are those of men confronted with a new civilization, which they tried to interpret according their own culture. Cortés was the most educated, and his letters are a valuable first account. Bernal Diaz del Castillo is more problematic: he wrote decades after the fact, he never learned the native languages, and he didn't take notes. His account is colorful, but the figures he gave are erratic and exaggerated.

The accounts of the first priests and schollars while tainted by their faith and they culture, are important sources. Father Diego Duran, Motolinia and Mendieta wrote with their own religion in mind. Bartolome de las Casas, instead wrote an apologetic view. There also authors that tried to make a sintesis of the prehispancis cultures, like "Oviedo y Herrera", Jose de Acosta, and Pedro Mártir de Angleria.

Maybe the most important source about the aztec, are the mounumental work of Bernardino de Sahagún, who worked with the surviving Aztec wise men, he also teached Aztec tlacuilos to write in european characters the original nahuatl accounts. Because of fear of the spanish autorities, he maintained anonimous his informants, and wrote a heavily censored version in spanish.

Another important sorces are indian and mestizo autors, descendents of the upper classes, like Don Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc, Chimalpain Cuahutlehuanintzin, Alva Ixtlixochitl, and Juan Bautista de Pomar. There are also some anonimous manuscripts like the Ramirez Codex, probably by an cristianized aztec.

Small comunities continued to use aztec codex for legal purpouses for almost a century after the conquest, altough they show they were made by untrained hands.

LINKS:

MARITIME HISTORY

GENERAL HISTORY

.. Thirst for Life

330ml Earth can - the World in Your Hands

|

||||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2012 Electrick Publications and Max Energy Limited, an educational charity working for world peace. The bird logos and name Solar Navigator are trademarks. All rights reserved. |

||||

|

AUTOMOTIVE | BLUEPLANET | ELECTRIC CARS | ELECTRIC CYCLES | SOLAR CARS | SOLARNAVIGATOR | UTOPIA |