|

HINDENBURG DISASTER

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

LZ 129 Hindenburg was a German zeppelin. Along with its sister-ship LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II, it was the largest aircraft ever built.

During its second year of service, it was destroyed by a fire while landing at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Manchester, New Jersey, USA, on May 6, 1937. Thirty-six people perished in the accident, which was widely reported by film, photographic, and radio media.

The Hindenburg was named after Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934), the President of Germany (1925–1934).

The

German zeppelin Hindenburg at Lakehurst - Hindenburg was the last passenger aircraft of the world’s first airline.

Her chief steward was the first flight attendant in history, and she was the fastest way to cross the

Atlantic in her day.

All that came to an end in 32 seconds because above the elegant passenger quarters were 7 million cubic feet of hydrogen gas.

Design and construction

The Hindenburg was built by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin in 1935 to a new, all-duralumin design. It was 245 m (804 ft) long and 41 m (135 ft) in diameter, longer than three Boeing 747s placed end-to-end and only 24 m (78 ft) shorter than the Titanic. It was originally equipped with cabins for 50 passengers and a crew complement of 61.

The Hindenburg was originally intended to be filled with helium, but a United States military embargo on helium led the Germans to modify the design of the ship to use flammable hydrogen as the lift gas. It contained 200,000 m³ (7,000,000 ft³) of gas in 16 bags or cells, with a useful lift of 1.099 MN (247,100 pounds).

Germany had extensive experience with hydrogen as lifting gas. Hydrogen-related fire accidents had never occurred on civil zeppelins, so the switch from helium to hydrogen did not cause much alarm. Hydrogen also gave the craft about 8% more lift capacity.

Four reversible 890 kW (1,200 horsepower) Daimler-Benz diesel engines gave the ship a maximum speed of 135 km/h (84 mph).

The duralumin frame was covered by cotton varnished with iron oxide and cellulose acetate butyrate impregnated with aluminium powder.

The total construction cost of the ship was £500,000 (US$2,500,000). It made its first flight on March 4, 1936. The cost of a ticket from Germany to Lakehurst was US$400 (about US$5900 in 2006 dollars), a tremendous amount of money for the Depression era; however, the Hindenburg's passengers were generally of the affluent classes or leaders of industry.

Passenger accommodations

To reduce drag, the passenger rooms were contained entirely within the hull, rather than in the gondola as on the Graf Zeppelin. The interior furnishings of the Hindenburg were designed by Professor Fritz Breuhaus, whose design experience included Pullman coaches, ocean liners, and warships of the German Navy. The upper A Deck contained small passenger quarters in the middle flanked by large public rooms: a dining room to port and a lounge and writing room to starboard. Paintings on the walls of the dining room portrayed the Graf Zeppelin's trips to South America. A stylized world map covered the wall of the lounge. Long slanted windows ran the length of both decks. The passengers were expected to spend most of their time in the public areas instead of their cramped cabins.

The lower B Deck contained washrooms, a mess hall for the crew, and a smoking lounge. Recalled Harold G. Dick, an American representative from the Goodyear Zeppelin Corporation, "The only entrance to the smoking room, which was pressurized to prevent the admission of any leaking hydrogen, was via the bar, which had a swivelling air-lock door, and all departing passengers were scrutinized by the bar steward to make sure they were not carrying out a lighted cigarette or pipe."

First year of service

During its first year of commercial operation in 1936, the Hindenburg flew 308,323 km (192,583 miles) carrying 2,798 passengers and 160 tons of freight and mail. It made 17 round trips across the Atlantic Ocean, with 10 trips to the US and seven to Brazil. In July of that year it also completed a record Atlantic double-crossing in five days, 19 hours and 51 minutes. The German boxer Max Schmeling returned home on the Hindenburg to a hero's welcome in Frankfurt, after defeating Joe Louis.

On August 1 the Hindenburg was present at the opening ceremonies of the eleventh modern day Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. Moments before the arrival of Adolf Hitler, the airship crossed over the Olympic stadium, trailing the Olympic flag from its gondola.

During its first year of service, the airship had a special aluminium Blüthner grand piano placed on board in the music salon. It was the first piano ever placed in flight and helped host the first radio broadcasted "air concert." The piano was removed after the first year to save weight.

The Hindenburg's success encouraged the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Company to plan the expansion of its airship fleet and transatlantic services.

During the winter of 1936–37, several changes were made. The greater lift capacity allowed 10 passenger cabins to be added, nine with two beds and one with four beds, increasing the total passenger capacity to 72.

The Last Flight

Weeks before the last flight, a letter from a Kathie Rauch of Milwaukee predicted that the Hindenburg would be sabotaged and explode. Because of this and similar bomb threats, there were a few Luftwaffe security officers on board, but it is unclear if anything was done by the Zeppelin Company about the bomb threats.

On the night of May 3, 1937, the Hindenburg left Frankfurt, Germany for Lakehurst, New Jersey.

The crossing was uneventful, except for strong headwinds. The ship was only half full, with only 36 passengers and 61 crew members, but the return flight was fully booked by people attending the coronation.

On May 6, the ship arrived in America. The ship was already very late, but the landing was further delayed because of bad weather. Captain Max Pruss took passengers on a tour through New York City, and the seasides of Boston and New Jersey.

Finally, at around 7:00 p.m. local time, altitude 650 feet, the Hindenburg approached the Lakehurst Naval Air Station. This landing was different, known as a high landing or flying moor, because the ship was winched down from a higher altitude. This type of landing manuever would save the number of ground crew, but would require more time. At around 7:08 the ship made a full-speed left turn to the west. A few minutes later the ship turns back towards the landing field and valves gas and all engines idle ahead and the ship began to slow. At 7:14, and altutude 394 feet, Captain Pruss ordered aft engine full astern to try to brake the ship. Later, at 7:19, the ship dropped 300, 300, and 500 kg of water ballast to try to correct the slight stern heaviness. Six men (all who were killed, including possible saboteur Eric Spehl) were also sent to the bow to trim the ship. None of these attempts to correct the problem worked, but Pruss was now permitted to land. At 7:21, altitude 295 feet, the mooring lines dropped from the bow. At this point, the cameramen were filming the lines being caught by the ground crew, and missed what was about to happen.

At 7:25, witnesses started reporting a small jet of flame near the vent in front of the upper fin. What happened next, shocked them.

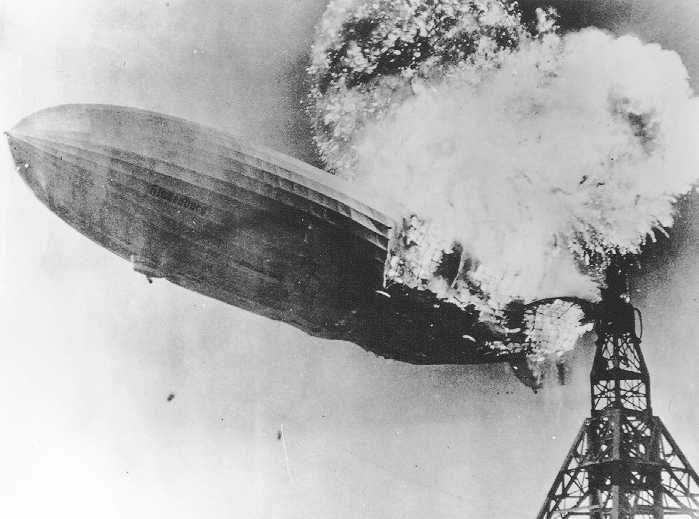

The German zeppelin Hindenburg moments after catching fire

Disaster

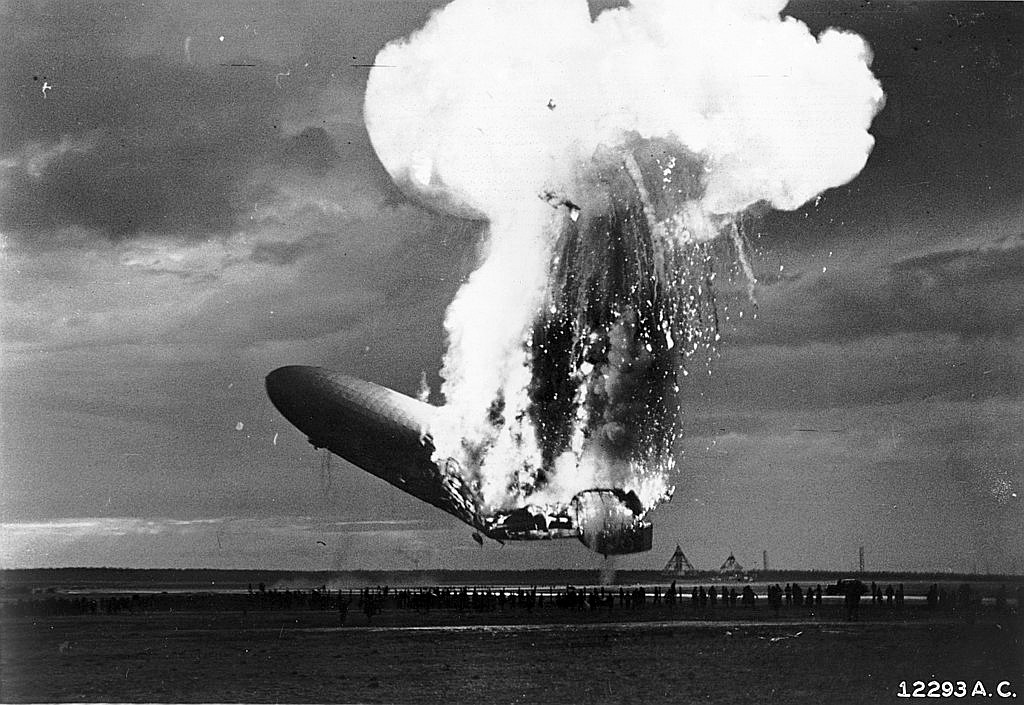

At 7:25 p.m. local time, the Hindenburg caught fire violently, sometimes described as an explosion. The fire started around cell 4, and quickly spread forward. The Hindenburg's back then broke,

Witnesses described it as a "fire of Hell", and said that it smelled like burnt flesh..

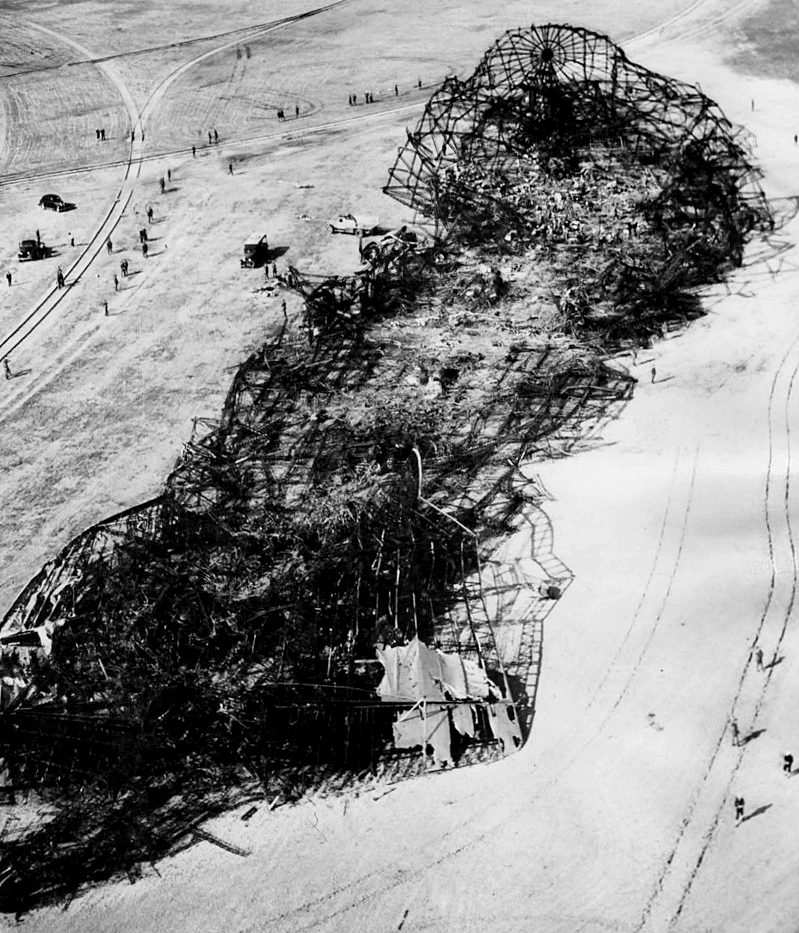

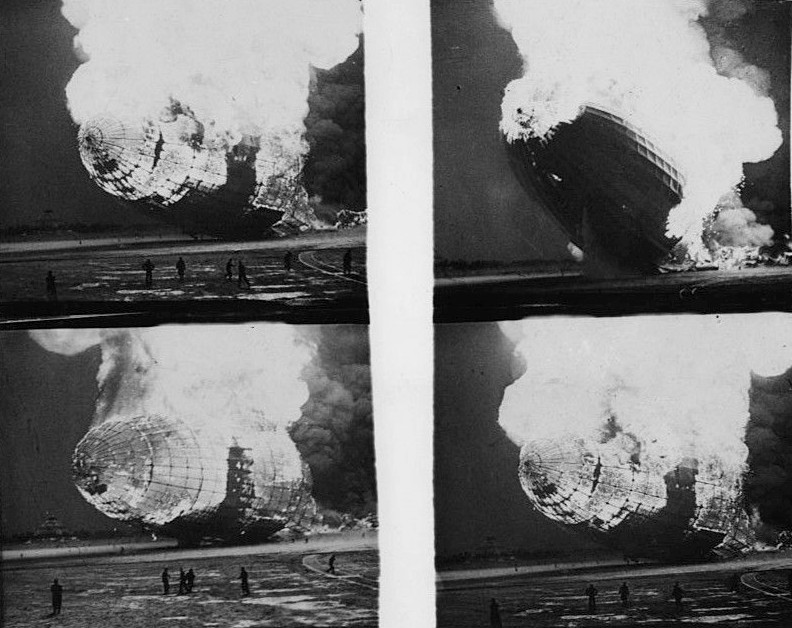

Then the ship's back broke, though the ship still remained as one piece and the nose was facing upwards. As the Hindenburg's tail crushed the ground, a burst of flame came out of the nose, killing all of the six crew members in the bow. As the ship kept falling with the bow faced upwards because there was more gas in the nose, part of the port side in front of the front engine and behind the passenger deck crushed in, and a third fire started, erasing the scarlet lettering "hindenburg" (uncapitalized) while the ship's bow lowered. The ship's gondola wheel touched the ground, causing the ship to bounce up once more. At this point, all of the fabric had burned away. At last, the ship went crushing on the ground, bow first.

The incident is widely remembered as one of the most dramatic accidents of modern time. The cause of the accident has never been determined, although many theories, some highly controversial, have been proposed.

Historic newsreel coverage

The disaster is well recorded because of an extraordinary amount of newsreel coverage and photographs, as well as Herbert Morrison's recorded, on-the-scene, eyewitness radio report from the landing field. Heavy publicity about the first transatlantic passenger flight of the year by Zeppelin to the US attracted a large number of journalists to the landing. Morrison's recording was not broadcast until the next day. Parts of his report were later dubbed onto the newsreel footage, giving a false impression to many modern viewers, more accustomed to live television reporting, that the words and film were recorded together. Morrison's broadcast remains one of the most famous in history. His plaintive words, "Oh, the humanity!" resonate with the impact of the disaster. Strangely, all the newsreel cameras missed the moment when the Hindenburg just caught fire.

Spectacular movie footage and Morrison's passionate recording of the Hindenburg fire shattered the public's faith in airships and marked the end of the giant, passenger-carrying dirigibles. Also contributing to the Zeppelins's downfall was the arrival of international passenger airplane travel and Pan American Airlines. Planes regularly crossed the Atlantic and Pacific oceans much faster than the 130 km/h (80 mph) of the Hindenburg. The one advantage that the Hindenburg had over airplanes was the comfort it afforded its passengers, much like that of an ocean liner.

There had been a series of other airship accidents, none of them Zeppelins, prior to the Hindenburg fire. Many were caused by bad weather, and most of these accidents were dirigibles of British and U.S. manufacture. Both nations' technologies in dirigible manufacture were primitive compared to the expertise of the Germans. Zeppelins had an impeccable safety record. The Graf Zeppelin had flown safely for more than 1.6 million km (1 million miles), including the first circumnavigation of the globe. The Zeppelin company was very proud of the fact that no passenger had been injured on one of their airships.

Death toll

Despite the violent fire, most of the crew and passengers survived. Of the 36 passengers and 61 crew, 13 passengers and 22 crew died. Also killed was one member of the ground crew, Navy Linesman Allen Hagaman. Most deaths did not arise from the fire but were suffered by those who leapt from the burning ship. (The lighter-than-air fire burned overhead.) Those passengers who rode the ship on its descent to the ground survived. Some deaths of crew members occurred because they wanted to save more people on board the ship. In comparison, almost twice as many perished when the helium-filled USS Akron crashed.

Controversies over cause of the accident

Among the many theories explaining the Hindenburg disaster, two are most prominent:

Theories seek to explain how the fire started, which material (gas or fabric) started to burn first, and which material caused the rapid spread of fire, which traveled the length of the aircraft at a rate of approximately 47 feet per second.

Wreckage of the Hindenburg in 1937

Cause of ignition

Sabotage theory

At the time of the disaster, sabotage was commonly put forward as the cause of the fire, in particular by Hugo Eckener, former head of the Zeppelin company and the "old man" of German airships. (Eckener later publicly endorsed the static spark theory, and see below.)

Another proponent of the sabotage hypothesis was Max Pruss, commander of the Hindenburg throughout the airship's career. Pruss flew on nearly every flight of the Graf Zeppelin until the Hindenburg was ready. In a 1960 interview conducted by Kenneth Leish for Columbia University's Oral History Research Office, Pruss said early dirigible travel was safe, and therefore he strongly believed that sabotage was to blame. He stated that on trips to South America, which was a popular destination for German tourists, both airships passed through thunderstorms, were struck by lightning, yet were unharmed.

Among sabotage theories are some that blame Zionist agents motivated by the Nazis' anti-Semitism. The Zeppelin airships were widely seen as symbols of German and Nazi power. Critics note, however, that the Zeppelin company was openly anti-Nazi. Hitler had wanted the airship named after him, but to prevent this, the company quickly named it after Paul von Hindenburg, the late German war hero, president, and non-Nazi.

In 1962, A. Hoehling published Who Destroyed the Hindenburg?, a book that rejects all theories but sabotage. It even names the likely saboteur -- Eric Spehl, a rigger on the Hindenburg who died in the fire. Ten years later, Michael MacDonald Mooney's book, The Hindenburg, also identified Spehl as the saboteur.

Those putting Spehl forward as a saboteur cite:

--His girlfriend's anti-Nazi connections; she reportedly was a communist and therefore opposed to the Nazis.

--The fire's origin near Gas Cell 4, Spehl's duty station.

--Rumors that in 1938 the Gestapo was investigating Spehl's involvement.

--Spehl's interest in amateur photography, making him familiar with flashbulbs that could have served as an igniter. A dry-cell battery that might have powered a flashbulb was found in the wreckage. Crew members near the lower fin had seen what they described as a flash or a bright reflection.

During the landing maneuver rigger Hans Freund dropped a landing line in front of the lower fin which was caught in the bracing wires of the ship, and No. 2 helmsman Helmut Lau climbed up from the lower fin to release it. When both men looked up toward the front of the ship, they were surprised by what they saw.

Freund described a flash like a flashbulb's, and Lau said he saw a brilliant reflection between cells 4 and 5, where some believe the fire began. They then heard a muffled detonation and a thud as the Hindenburg's back broke. Some believe that this is evidence that the airship was sabotaged. Others believe Freund was actually looking rearward away from cells 4 and 5.

Another suspect was a passenger, a German acrobat named Joseph Spah, who survived the fire. He brought with him a dog, a German shepherd named Ulla, as a surprise for his children. (Ulla did not survive.) He often visited the dog to feed, talk, and play with it. Some, noting that Spah told many anti-Nazi jokes, accuse him of planting a bomb when he was with his dog.

It has even been suggested that Adolf Hitler himself had ordered the Hindenburg to be destroyed in retaliation for Eckener's anti-Nazi opinions.

However, opponents of the sabotage hypothesis argued that only speculation supported sabotage as a cause of the fire, and no credible evidence of sabotage was produced at any of the formal hearings. The sabotage theory was fostered by the children of Max Pruss merely to exonerate their father, opponents assert.

They argue that Spehl is a convenient scapegoat, because he died in the fire and was unable to refute the accusations. The FBI investigated Spah and reported finding no significant evidence of sabotage.

Opponents point to the fact that neither the German nor the American investigation endorsed any of the sabotage theories. Proponents of the sabotage theory argue that any finding of sabotage would have been an embarrassment for the Nazi regime, and they speculate that such a finding was suppressed for political reasons. Opponents reply that no such political pressure would have been applied to the American inquiry, which also concluded against sabotage. They argue that the postwar memoirs of Eckener and Hans von Schiller contain no support for the notion of "suppressed investigation findings." Given the timing of the memoirs - after the war when the Nazis had fallen - there would be little incentive for these two airship men to perpetuate any cover-up. This is particularly true of Eckener, who had been extremely vocal in his opposition to the Nazis during their rise to power.

The theory that hydrogen was ignited by a static spark is the most widely accepted theory as determined by the official crash investigations. Offering support for the hypothesis that there was some sort of hydrogen leak prior to the fire is that the airship remained stern-heavy before landing, despite efforts to put the airship back in trim. This could have been caused by a leak of the gas, which started mixing with air, potentially creating a form of oxyhydrogen and filling up the space between the skin and the cells.

Static spark theory

Another theory posits that the fire was started by a spark caused by a buildup of static electricity on airship.

Proponents of the static spark theory point out that the airship's skin was not constructed in a way that allowed its charge to be evenly distributed throughout the craft. The skin was separated from the duralumin frame by nonconductive ramie cords, in effect electrically insulating the skin from the frame and allowing a potential difference to form between them.

In order to make up for a delay of more than 12 hours in its transatlantic flight, the Hindenburg passed through a weather front of high humidity and high electrical charge. This made the airship's mooring lines wet and thus conductive and may have given its skin an electrical charge. When the wet mooring lines, which were connected to the frame, touched the ground, they would have grounded the frame but not the skin. That could have caused a sudden potential difference between skin and frame and set off an electrical discharge - a spark.

Some witnesses reported seeing a glow consistent with St. Elmo's fire along the tail portion of the ship just before the flames broke out, but these reports were made after the official inquiries were completed.

The Hindenburg had a cotton skin covered with a finish known as "dope". It is a common term for a plasticised lacquer that provides stiffness, protection, and a lightweight, airtight seal to woven fabrics. In its liquid forms, dope is highly flammable. When the mooring line touched the ground, a resulting spark could have ignited the dope in the skin.

Harold G. Dick was Goodyear Zeppelin's representative with Luftshiffbau Zeppelin during the mid-1930s. He flew on test fights of the Hindenburg and its sister ship, the Graf Zeppelin II. He also flew on numerous flights in the original Graf Zeppelin and ten round-trip crossings of the north and south Atlantic in the Hindenburg. On page 149 of his book, The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships Graf Zeppelin & Hindenburg, he observes:

In addition to Dick's observations is the fact that during the Graf Zeppelin II's early test flights, measurements were taken of the airship's static charge. It is clear that Dr. Ludwig Durr and the other engineers at Luftshiffbau Zeppelin took the static discharge theory seriously and considered the insulation of the fabric from the frame to be a design flaw in the Hindenburg.

A variant of the static spark theory, presented by Addison Bain, is that a spark between segments of the Hindenburg itself started the fire.

Lightning theory

A. J. Dessler, former director of the Space Science Laboratory at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and a critic of the incendiary paint theory (see below), favors a much simpler explanation for the conflagration: natural lightning. Like many other aircraft, the Hindenburg had been struck by lightning several times. This does not normally ignite a fire in hydrogen-filled airships, because the hydrogen is not mixed with oxygen. However, many fires have been started by lightning striking while airships were venting hydrogen in preparation for landing, as the Hindenburg was doing at the time of the disaster. The vented hydrogen is mixed with air, making it readily combustible. Dessler cites an airship rule from the time: "Never blow off gas during a thunderstorm."

Almost 80 years of research and scientific tests support the same conclusion reached by the original German and American accident investigations in 1937: It seems clear that the Hindenburg disaster was caused by an electrostatic discharge (a spark) that ignited leaking hydrogen.

Fire's initial fuel

Most current analysis of the fire assumes that ignition due to some form of electricity was the cause. However, there is still controversy over whether the fabric covering of the ship or the hydrogen used for buoyancy was the initial fuel for the fire.

The incendiary paint theory

The incendiary paint theory (IPT) asserts that the major component in the fire was the skin because of the doping compound used on it.

Proponents point out that the coatings on the fabric contained both iron oxide and aluminum-impregnated cellulose acetate butyrate (CAB). These components are potentially reactive. In fact, iron oxide and aluminum are sometimes used as components of solid rocket fuel or thermite. The propellant for the Space Shuttle solid rocket booster includes "aluminum (fuel, 16%), (and) iron oxide (a catalyst, 0.4%)"

Addison Bain received permission from the German government to search its archives and discovered that during the Nazi regime, German scientists concluded that the dope on the Hindenburg's fabric skin was the cause of the conflagration. Bain interviewed the wife of the investigation's lead scientist, and she confirmed that her husband had told her about the conclusion and instructed her to tell no one, presumably because it would likely have embarrassed the Nazi government.

The hydrogen theory

Those who believe hydrogen was the initial fuel discount arguments for the incendiary paint theory as not credible. They point out that cellulose acetate butyrate (CAB) varnish is rated within the plastics industry as combustible but nonflammable. That is, it will burn when placed in a fire but is not readily ignited by itself. In fact, it is considered to be self-extinguishing. That so many pieces of the Hindenburg's skin remained despite such a fierce fire is cited as proof. In his experiment, Addison Bain had to use a high-energy ignition source and orient the fabric carefully to make it burn.

While aluminum and iron oxide components of the fabric doping compounds are potentially reactive, they were in incorrect proportions, were applied on only part of the airship, and were separated by a layer of CAB that would have prevented their mingling and reacting.

Critics point out that witnesses on the field, as well as crew members stationed in the stern, saw a glow inside Cell 4 before any fire broke out of the skin, indicating that the fire began inside the ship. Newsreel footage supports this. Photographs of the early stages of the fire show the gas cells of the Hindenburg's entire aft section fully aflame. Burning gas spewing upward from the top of the ship was causing low pressure inside, allowing atmospheric pressure to press the skin inwards. If the gas was not burning but the envelope was, this would not have happened.

Proponents' argument that the airship's nose remained airborne for a while because the hydrogen cells were intact overlooks the effects of buoyancy forces and the inertia of the ship's considerable mass, critics argue. They point to pictures which show the fire burning along straight lines that coincide with the boundaries of gas cells. This suggests that the fire was not burning along the skin, which was continuous. Crew members stationed in the stern reported actually seeing the cells burning.

Some proponents of the incendiary paint theory claim that the hydrogen was odorised with garlic, yet nobody reported smelling the odor of garlic. That no one detected a garlic smell does not prove the absence of a hydrogen leak, opponents argue. Odorised hydrogen would have been detected only in the area of a leak. The fire started near the top of the airship far from any crew or passengers. Once the fire was underway, more powerful smells would have masked any garlic odor. Opponents also argue there is no documentation that the hydrogen was odorised.

COMPRESSED GAS - ECONOMY - FUEL CELLS - FUSION - HYDRIDES - LIQUID GAS

MythBusters

The Discovery Channel series MythBusters explored the incendiary paint and hydrogen theories in an episode that aired January 10, 2007 Using a 1:50 scale model, the show's hosts, Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman, demonstrated that while a thermite reaction was possible with the Hindenburg's skin and was a significant factor in the fire, hydrogen was the main fuel. The model burned twice as quickly when it was filled with hydrogen instead of inert gases and produced a fire which visually matched the newsreel footage quite well.

The program concluded that both the hydrogen and the paint contributed to the disaster.

Rate of flame propagation

Regardless of the source of ignition or the initial fuel for the fire, there remains the question of what caused the rapid spread of flames along the length of the ship. Here again the debate has centered on the fabric covering of the ship and the hydrogen used for buoyancy.

The proponents of the incendiary paint theory also contend that the fabric coatings were responsible for the rapid spread of the fire. They point out that the combustion of hydrogen is not visible, because it burns in the ultraviolet range. Thus what can be seen burning in the photographs cannot be hydrogen. The motion picture films show the fire spreading downward along the skin of the airship.

The proponents of the hydrogen theory point out that once the fire started, all of the components of the ship (fabric, gas, metal, etc.) burned. Thus the presence of color in the flames does not prove that hydrogen was not burning. And while fires generally tend to burn upward, including hydrogen fires, the enormous radiant heat from the blaze would have quickly spread fire over the entire surface of the ship, thus explaining the downward propagation of the flames. Some also think that what looked like downward burning was in fact burning pieces of fabric, metal and other materials. They observe that World War I airships filled with hydrogen but constructed of completely different materials also burned visibly, suggesting that the glow is produced mechanically like a gas lantern.

Those skeptical of the incendiary paint theory cite recent technical papers which claim that even if the ship had been coated with actual rocket fuel, it would have taken many hours to burn — not the 32 to 37 seconds that it actually took. Proponents claim that this criticism does not take into account the conditions that lead to firestorms, such as convection and ignition from radiant energy.

Modern experiments that recreated the fabric and coating materials of the Hindenburg seem to discredit the incendiary fabric theory.

They conclude that it would have taken about 40 hours for the Hindenburg to burn if the fire had been driven by combustible fabric. Two additional scientific papers also strongly reject the fabric theory.

END

OF AN ERA - The public seemed remarkably forgiving of the accident-prone zeppelin prior to the Hindenburg disaster, and the glamorous and speedy Hindenburg was greeted with public enthusiasm despite a long list of previous airship accidents.

Other controversial hypotheses

Structural Failure

Although Captain Pruss believed that the Hindenburg could withstand tight turns without significant damage, others believe that the ship would have been weakened by being repeatedly stressed. Even a 33-foot, full-scale replica of the Hindenburg's passenger quarters, displayed in the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen, has developed some metal fatigue.

The ship did not receive much routine inspection, even though there was evidence of damage on previous flights. The Hindenburg once lost an engine and almost drifted over Africa, where it could have crashed. Dr. Eckener was furious and ordered all section chiefs to inspect the ship during flight.

In March 1936, the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg made three-day flights to drop leaflets and broadcast speeches via loudspeaker. On one day during this tour, Captain Ernst Lehmann flew the Hindenburg at full power in very gusty conditions to impress spectators. The ship's tail struck the ground, and part of the lower fin was broken.

Many spectators' cameras were confiscated to prevent negative publicity, but Harold G. Dick concealed his camera and took pictures of the damaged fin. Dr. Eckener was very upset and rebuked Captain Lehmann:

The Hindenburg can also be seen in photographs and newsreels of the disaster cracking or bending, leading some to believe that the ship's structure was weak.

This theory of the cause of the fire has not been very popular, because it requires the puncture theory (see below).

DURALUMIN - One section of spar from the fated Hindenburg zeppelin.

Puncture theory

Newsreels show the Hindenburg making a sharp turn just before bursting into flames. Some speculate that one of the many bracing wires within the airship snapped and punctured at least one of the internal gas cells. Gauges found in the wreckage showed the tension of the wires was much too high. Some of the wires may have been substandard. One bracing wire tested after the crash broke at only 70% of its rated load. A punctured cell would have freed hydrogen into the air and could have been ignited by a static discharge.

Some witnesses reported seeing a piece of the airship's fabric flapping, perhaps providing an opening for a spark to reach escaping hydrogen inside the airship. These witnesses said that the fire began there. Persons on board the ship also reported hearing a muffled sound, and a ground crew member on the starboard side reported hearing a crack. Some speculate the sound was from a bracing wire snapping.

Dr. Eckener may have been among those who subscribed to the puncture theory. He blamed Captain Max Pruss for rushing and mishandling the landing maneuver. Privately at least, he believed Pruss was to blame for the disaster.

Advocates of this theory believe that the hydrogen began to leak approximately eight minutes before the fire, building up until a spark ignited the gas. This theory, however, remains speculation, because no concrete evidence has shown that the gas cells were punctured.

Fuel leak

The 2001 documentary Hindenburg Disaster: Probable Cause suggested that a 16-year-old boy, who said he had smelled "gasoline" when he was standing below the Hindenburg's aft port engine, had detected a diesel fuel leak. The resulting vapor would have been highly flammable and could have ignited the ship. The film also suggested that overheating engines may have played a role.

During the investigation, Commander Charles Rosendahl dismissed the boy's report.

Critics say the documentary is misleading, because it misconstrued the statements by the crewmen in the Hindenburg's lower fin. The crewmen said they saw a flash in the axial catwalk, but the film placed the flash in the keel catwalk closer to the passenger areas.

COMEBACK - Hydrogen could make a comeback despite the flammability of the fuel, if other ways of providing sustainable transport are not developed. The lessons we learned from airship fires seem to have been lost. That said, and despite the inefficiencies of the hydrogen energy chain, hydrogen could play a part in a circular economy, provided it is safe and there are no explosions.

Hydrogen Fuel Cells and Economy

Despite the dangers of hydrogen when stored as a compressed gas or in liquid form, the recent climate change emergency had triggered a number of projects to split water using electrolysis and renewables energy supplies from solar and wind farms, liquefy the gas and transport and then store the fuel for cars, buses and ships.

Luger pistol among wreckage

Some more sensational newspapers at the time said that a person on board committed suicide because a Luger pistol with one shell fired was found among the wreckage. Another possibility would be that the Hindenburg was shot with the pistol. Most historians discount this story as having only circumstantial and incidental evidence.

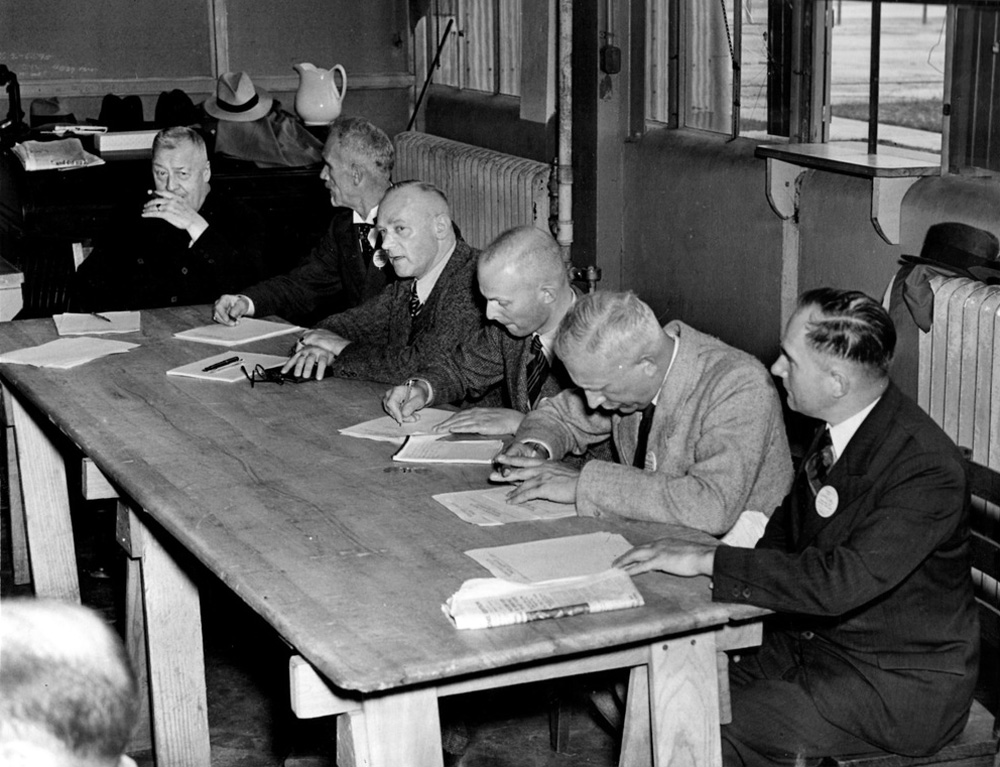

List of Officers and Crew

Two other airship captains were also on board as observers; Captain Ernst Lehmann, who had commanded Hindenburg on many flights and was director of the DZR, and Captain Anton Wittemann, who was the regular captain of LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin. (Wittemann would have been in command of Graf Zeppelin at the time of the Hindenburg disaster, but he had switched positions with Captain Hans von Schiller, who took Graf Zeppelin on a roundtrip to South America so he could attend a reunion in Germany.)

In all, there were six qualified zeppelin captains in the control car when Hindenburg crashed at Lakehurst.

OFFICERS

Cultural references

Audio

Film

The following is a partial list of airship accidents involving fires, crashes and deaths.

LINKS and REFERENCE

Botting, Douglas (2001). Dr. Eckener's Dream Machine. Henry Holt, 249-251. ISBN 0805064583. data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl Lehmann, Ernst (1937). Zeppelin: The Story of Lighter-than-air Craft. Longmans, Green and Co., 319. ISBN. Dick, Harold (1985). The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg. Smithsonian Institution Press, 96. ISBN 1560982195. Dick, Harold (1985). The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg. Smithsonian Institution Press, 97. ISBN 1560982195. Berg, Emmett (July/August 2004). Fight of the Century. Humanities vol 25 no 4. Birchall, 1936 A history of the Blüthner Piano Company. National Geographic, Hindenburg's Fiery Secret. Source for the cause of death is secondary. Found on page 35 of Hawken, P, Lovins, A & Lovins H, 1999, "Natural Capitalism", Little Brown & Company, New York. Their footnote references Bain, A, 1997, "The Hindenberg Disaster: A Compelling Theory of Probable Cause and Effect", Procs. Natl. Hydr. Assn. 8th Ann. Hydrogen Mtg. (Alexandria, VA) March 11-13 pp. 125-128. this however is not true,the hydrogen fire would have just exploded into the air the real culprit was the paint,wich had many of the same ingredients as rocket fuel. spot.colorado.edu/~dziadeck/zf/LZ129fire.pdf www.bluenotebooks.com/coming.htm Archibold, Rick, Hindenburg: An Illustrated History, ISBN 0-7858-1973-8 Moondance Films, Hindenburg Disaster: Probable Cause (2001), also known as Revealed...The Hindenburg Mystery (2002). What Happened to the Hindenburg?, PBS www.keepgoing.org/issue20_giant/thirtytwo_seconds.html Citizen Scientist on the flammable coating (IPT) Birchall, Frederick (August 1, 1936). "100,000 Hail Hitler; U.S. Athletes Avoid Nazi Salute to Him". The New York Times, p. 1. Duggan, John (2002). LZ 129 "Hindenburg" — The Complete Story. Ickenham, UK: Zeppelin Study Group. ISBN 0-9514114-8-9. Harold G. Dick & Douglas H. Robinson "The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships Graf Zeppelin & Hindenburg." Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985.*/+ Page at Great Zeppelins website, with various pictures Footage from Castle and Pathé coverage of the Hindenburg disaster An Article Supporting the Flammable Fabric Theory Two Articles Rejecting the Flammable Fabric Theory Experiments Reject the Flammable Fabric Theory FBI investigation into the Hindenburg disaster Harold G. Dick was an American engineer who flew on most Hindenburg flights. Hindenburg Fire Video at Internet Archive "The Hindenburg" - Failure Magazine (January 2002) YouTube video of Herb Morrison's famous newsreel Zeppelin Company -- the company is still in the airship business today An article about the disaster that features rare photos of the disaster. "Bird's Eye View" of crash site marker What Happened to the Hindenburg? Transcript - Secrets of the Dead (June 15, 2001, PBS) https://www.airships.net/hindenburg/disaster/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindenburg_disaster

COMPRESSED

GAS - ECONOMY

- FUEL

CELLS - FUSION

- HYDRIDES

- LIQUID

GAS

AVIATION A - Z

A taste for adventure capitalists

Solar Cola - a healthier alternative

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2019. The bird logos and name Solar Navigator are trademarks. All rights reserved. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity.

|