|

|

|

|

The 7 December 1941 Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor was one of the great defining moments in history. A single carefully-planned and well-executed stroke removed the United States Navy's battleship force as a possible threat to the Japanese Empire's southward expansion. America, unprepared and now considerably weakened, was abruptly brought into the Second World War as a full combatant.

Eighteen months earlier, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had transferred the United States Fleet to Pearl Harbor as a presumed deterrent to Japanese aggression. The Japanese military, deeply engaged in the seemingly endless war it had started against China in mid-1937, badly needed oil and other raw materials. Commercial access to these was gradually curtailed as the conquests continued. In July 1941 the Western powers effectively halted trade with Japan. From then on, as the desperate Japanese schemed to seize the oil and mineral-rich East Indies and Southeast Asia, a Pacific war was virtually inevitable.

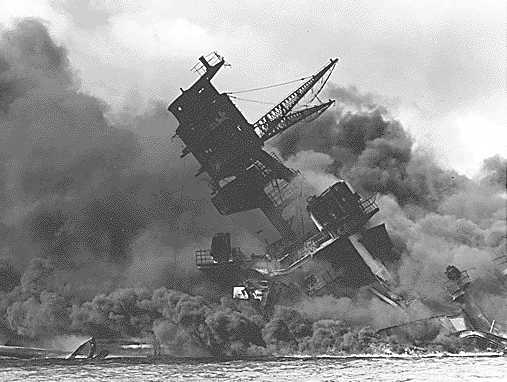

USS Arizona burned for two days after being hit. The wreck remains at bottom of Pearl Harbor and is a war memorial leaking a quart of oil a day

By late November 1941, with peace negotiations clearly approaching an end, informed U.S. officials (and they were well-informed, they believed, through an ability to read Japan's diplomatic codes) fully expected a Japanese attack into the Indies, Malaya and probably the Philippines. Completely unanticipated was the prospect that Japan would attack east, as well.

The U.S. Fleet's Pearl Harbor base was reachable by an aircraft carrier force, and the Japanese Navy secretly sent one across the Pacific with greater aerial striking power than had ever been seen on the World's oceans. Its planes hit just before 8AM on 7 December. Within a short time five of eight battleships at Pearl Harbor were sunk or sinking, with the rest damaged. Several other ships and most Hawaii-based combat planes were also knocked out and over 2400 Americans were dead. Soon after, Japanese planes eliminated much of the American air force in the Philippines, and a Japanese Army was ashore in Malaya.

These great Japanese successes, achieved without prior diplomatic formalities, shocked and enraged the previously divided American people into a level of purposeful unity hardly seen before or since. For the next five months, until the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May, Japan's far-reaching offensives proceeded untroubled by fruitful opposition. American and Allied morale suffered accordingly. Under normal political circumstances, an accommodation might have been considered.

However, the memory of the "sneak attack" on Pearl Harbor fueled a determination to fight on. Once the Battle of Midway in early June 1942 had eliminated much of Japan's striking power, that same memory stoked a relentless war to reverse her conquests and remove her, and her German and Italian allies, as future threats to World peace.

The Imperial Japanese Navy made its attack on Pearl Harbor on the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941 (Hawaii time, because of the International Date Line, Monday, December 8 in Japan). The surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaii, was aimed at the Pacific Fleet of the United States Navy and its defending Army Air Corps and Marine defensive squadrons.

The attack severely damaged or destroyed 12 American warships, destroyed 188 aircraft, and killed 2,403 American servicemen and 68 civilians. However, the Pacific Fleet's three aircraft carriers were not in port and so were undamaged, as were the base's vital oil tank farms, submarine pens, and machine shops. Using these resources, the United States was able to rebound within a year.

This attack has also been called the "bombing of Pearl Harbor" and the "Battle of Pearl Harbor" but, most commonly, the "attack on Pearl Harbor" or simply "Pearl Harbor".

Ensign of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force

Background

After the Meiji Restoration, Imperial Japan embarked on a period of rapid economic, political, and military expansion in an effort to achieve parity with the European and North American powers. The strategy for expansion included extending territorial and economic control to increase access to natural resources.

In executing this strategy, Japan embarked on a number of military adventures that brought it into conflict with neighboring countries. These included a war with China in 1894 in which Japan took control of Taiwan, and a war with Russia in 1904 by which Japan gained territory in and around China and the Korean peninsula. After WWI, the League of Nations awarded Japan custody of most Imperial German possessions and colonies in the Far East and Pacific waters. In 1931, Japan forcibly imposed a "puppet" state in Manchuria which they called Manchukuo.

From about 1910 through the 1930s the country had been extensively militarized, having created a large and modern Navy (the third largest in the world at the time) and Army. In 1937, Japan army officers staged a provocation at the Marco Polo Bridge, beginning a large-scale invasion of mainland China, attacking from Manchuria and at several points along China's Pacific coast.

The League of Nations, the U.S., the UK, Australia, and the Netherlands, all of whom had territorial interests in Southeast Asia disapproved of the Japanese attacks on China, and responded with condemnation and diplomatic pressure. Japan resigned from and walked out of the League of Nations in protest. In July of 1939, the U.S. upped the pressure on Japan by terminating the 1911 U.S./Japanese commerce treaty, which both showed official disapprobation and removed legal barriers to imposing trade embargoes. Japan continued its military campaign in China and signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Nazi Germany, formally ending World War I hostilities, and declaring common interests. In 1940, Japan signed Tripartite Pact with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy to form the Axis Powers.

Japanese actions caused the U.S. to place embargoes on scrap metal and gasoline and to close the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. The situation continued to worsen, and in 1941 Japan moved into northern Indochina. The U.S. response was to freeze Japan's assets in the U.S. and to initiate a complete oil embargo. Oil was probably Japan's most crucial resource, as its own supplies were very limited and 80% of Japan's oil imports came from the U.S. Certainly the Navy relied entirely on imported bunker oil stocks.

Diplomatic negotiations climaxed with the Hull note of November 26, 1941, which Prime Minister Hideki Tojo described to his cabinet as an ultimatum. Japan felt it had to choose between complying with the U.S. and UK demands — thus backing down from its aggression in China and the surrounding areas — and continuing with its expansionism. Concerned about losing hard-earned status and prestige in the international community if Japan backed down ("loss of face") and the perceived threat to its national security posed by the Western Powers who controlled territory in the Pacific and/or East Asia, Imperial Japan under Emperor Hirohito had already prepared military options, and decided to carry them out, thus choosing the latter option and war with the United States, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Having already signed the Axis Pact with Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and others, this meant that Japan would be fighting against the Allied Powers along with her allies.

On September 4, 1941, at the second of two Imperial Conferences attended by the Emperor considering an attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Cabinet met to consider the attack plans prepared by Imperial General Headquarters. It was decided that:

Japanese preparations

Japan had been impressed with Admiral Andrew Cunningham's Operation Judgement (the Battle of Taranto), where 20 nearly-obsolete biplanes (Fairey Swordfish) launched from a carrier force far in advance of the main British base at Alexandria disabled half the Italian battle fleet and forced the withdrawal of the Italian fleet to behind Naples. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto dispatched a naval delegation to Italy, which concluded that a larger and better-supported version of Cunningham's brilliant maneuver could force the U.S. fleet back to California, giving time to achieve the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere"—shorthand for control of the oil reserves of the Dutch East Indies, with a defensible buffer around them. Most importantly, the delegation returned to Japan with the secret of the shallow running torpedo which Cunningham's "boffins" had devised.

Additionally, some Japanese strategists may have been influenced by the actions of U.S. Admiral Harry Yarnell in the 1932 joint Army-Navy exercises, which assumed an invasion of Hawaii. Yarnell, playing the role of Commander of the attacking fleet, sailed his aircraft carriers northwest of Oahu in rough weather, and launched 'attack' planes on the morning of Sunday, 7 February 1932. Judges assigned to the exercise noted that Yarnell's aircraft were able to inflict serious 'damage' on the defenders, who were unable to locate his fleet for 24 hours after the attack. Conventional U.S. Navy doctrine of the time (and other naval opinion as well) believed that any attacking force would be set upon and destroyed by the battleship fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor, and dismissed Yarnell's strategy as impractical in the real world.

Yamamoto began considering such an attack early in 1941, and after some pressure on Naval Headquarters (including a threat to resign), managed to get permission to begin formal planning and training. The events of the summer (see above) led to preliminary approval of the attack plan at an Imperial Conference (which included the Emperor) and then approval of the attack in another Imperial Conference early in November.

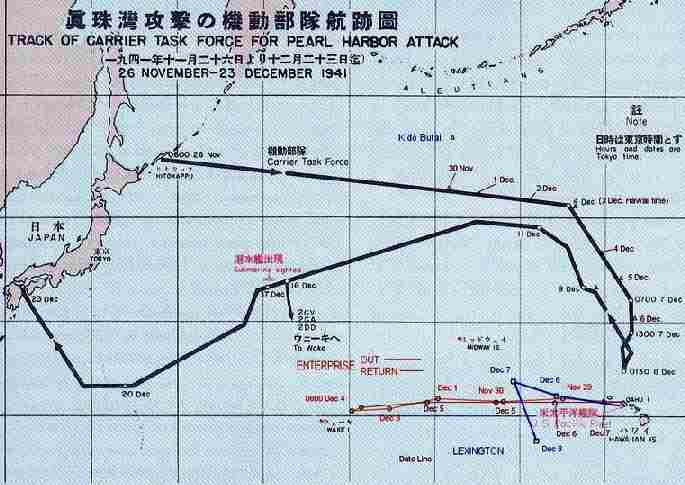

The Japanese fleet steamed towards Pearl Harbor undetected until the last moment

The intent of the attack on Pearl Harbor was to neutralize American naval power in the Pacific, if only temporarily, as part of a theater-wide, near-simultaneous coordinated attack against several different countries. Yamamoto himself expected that even a successful attack would gain only a year or so of freedom of action before the U.S. fleet recovered enough to check Japan's advances. Preliminary planning for a Pearl Harbor attack in support of military advance elsewhere began in January 1941, and, after some Imperial Navy factional infighting, the project was finally judged worthwhile. Training for the mission was under way by mid-year. The planned attack depended primarily on torpedoes, but the weapons of the time required deep water to function if air-launched. This was a critical problem because Pearl Harbor is shallow, except in dredged channels. Over the summer of 1941, Japan secretly created and tested torpedo modifications that could be expected to work properly in a shallow water drop. The effort resulted in the Type 95 torpedo which inflicted most of the damage to U.S. ships during the attack. Japanese weapons technicians also produced special armor-piercing bombs by fitting fins on 14 and 15 inch (356 and 381 mm) naval gun shells. These were able to penetrate the armored decks of battleships and cruisers when dropped from 10,000 feet (3,000 m), if they could actually hit them.

On November 26, 1941, a fleet including six aircraft carriers commanded by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo left Hitokappu Bay in the Kuril Islands under orders for strict radio silence bound for Hawaii.

Nakajima B5N2 "Kate"

The aircraft carriers involved in the attack were: Akagi, Hiryu, Kaga, Shokaku, Soryu, and Zuikaku. Two fast battleships, 2 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, 9 destroyers, and 3 fleet submarines provided escort for the task force. The carriers had a total of 423 planes, including Mitsubishi Type 0 "Zero" fighters, Nakajima Type 97 "Kate" torpedo bombers, and Aichi Type 99 "Val" dive bombers. Japan's task force and its air group were larger than any prior aircraft carrier-based strike force. Accompanying the fleet were 8 tankers for refueling. In addition, the Advanced Expeditionary Force included 20 fleet submarines and five two-man Ko-hyoteki-class midget submarines; they were to gather intelligence and sink any U.S. vessels that might try to flee Pearl Harbor during the air attack.

Admiral Husband E. Kimmel commander-in-chief U.S. Pacific Fleet

United States preparedness

Battleship Row presented an attractive concentration of targets

In 1924, General Billy Mitchell delivered a 324 page report to his superiors warning of a future war with Japan, including an attack on Pearl Harbor, which was ignored. He probably repeated this information at his court-martial in 1926. By 1941, General Mitchell's warnings had been forgotten by the United States.

U.S. civilian and military intelligence forces had, between them, good information suggesting additional Japanese aggression throughout the summer and fall before the attack. None of it specifically indicated an attack against Pearl Harbor. Public press reports during that summer and fall, including Hawaiian newspapers, contained extensive reports on the tension and developments in the Pacific. During November, all Pacific commands, including both the Navy and Army in Hawaii, were explicitly warned that war with Japan was expected in the very near future. And, on the day of the attack, General Marshall sent an imminent-war warning message to Pearl Harbor specifically. In Hawaii, there were several indications of the incoming attack, but none caused increased local readiness by defenders. Had any of these warnings produced an active alert status, the attack would have been resisted more effectively and perhaps caused much less death and damage. The attack arrived at a Pearl Harbor that was in fact unprepared: anti-aircraft weapons were not manned, ammunition was locked down, anti-submarine measures were not implemented (no submarine nets, for instance), combat air patrols were not flying, scouting aircraft not in the air at first light, etc.

U.S. signals intelligence, through the Army Signal Intelligence Service and the Office of Naval Intelligence's OP-20-G unit, intercepted Japanese diplomatic traffic and had broken many Japanese ciphers, though none carried either strategic or tactical military information. Distribution of this intelligence was capricious and confusing, and did not include material from Japan's military traffic as this was not available. At best the information was (as is common in such cases) partial, seemingly contradictory, or insufficiently distributed (as in the case of the Winds Code). Warnings were sent to all U.S. forces commands in the Pacific, including the explicit war warning message in late November 1941. Despite the growing information pointing to a new phase of Japan's aggression, there was little information available pointing specifically toward Pearl Harbor.

American commanders had been warned that tests had shown that shallow-water torpedo air launches were possible, but no one in charge in Hawaii fully appreciated the danger posed by the new possibilities. Expecting that Pearl Harbor had natural defenses against torpedo attack (e.g., shallow water), the U.S. Navy failed to deploy torpedo nets or baffles, which they judged an interference with ordinary operations and so, a low priority. Due to a claimed shortage of long-distance planes, long reconnaissance patrols (chiefly Navy flying boats and Army Air Corps bombers) were not being made as often as required for adequate coverage, or as were shown to be possible (eg, immediately after the attack and with fewer planes). At the time of the attack, the Army, which was responsible for the defense of Pearl Harbor, was in training mode rather than on an alert footing. Most of its portable anti-aircraft guns were stowed, with the ammunition locked in separate armories. To avoid upsetting property owners, officers did not keep guns dispersed around the Pearl Harbor base (i.e., on private property).

Breaking off negotiations

Part of the Japanese plan for the attack included breaking off negotiations with the United States 30 minutes before the attack began. Diplomats from the Japanese Embassy in Washington, including the Japanese Ambassador, Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura, and special representative Saburo Kurusu, had been conducting extended talks with the State Department regarding the U.S. reactions (see above) to the Japanese move into Indochina in the summer.

In the days before the attack, a long multi-part message was sent to the Embassy from the Foreign Office in Tokyo (encoded with the PURPLE cryptographic machine), with instructions to deliver it to Secretary of State Cordell Hull at 1 PM Washington time (ie, just thirty minutes before the attack was scheduled to begin). The last part arrived not long before the attack, but because of decryption and typing delays, Embassy personnel failed to deliver the message at the specified time. The last part, breaking off negotiations ("Obviously it is the intention of the American Government to conspire with Great Britain and other countries to obstruct Japan's efforts toward the establishment of peace through the creation of a new order in East Asia ... Thus, the earnest hope of the Japanese government to adjust Japanese-American relations and to preserve and promote the peace of the Pacific through cooperation with the American Government has finally been lost"), was delivered to Secretary Hull several hours after the Pearl Harbor attack.

The United States had decrypted the last part of the final message well before the Japanese Embassy managed to, and long before a fair typed copy of the decrypt was finished. It was decryption of the last part with its instruction for the time of delivery which prompted Gen. George Marshall to send his famous warning to Hawaii that morning. It was actually delivered, by a young Japanese-American cycle messenger, to Gen. Walter Short at Pearl Harbor several hours after the attack had ended. The delay was due to an inability to locate General Marshall after decryption and translation (he was out riding), trouble with the Army's long distance communication system, a decision not to use Navy facilities to transmit it, and various troubles during its travels over commercial cable facilities. Somehow its "urgent" marking was misplaced during its travels and it was delayed by several additional hours.

Japan's records, admitted into evidence during Congressional hearings on the attack after the War, established that the Japanese government had not even written a declaration of war until after they heard of the successful attack on Pearl Harbor. That two-line declaration of war was finally delivered to U.S. Ambassador Grew in Tokyo about 10 hours after the attack was over. He was allowed to transmit it to the United States where it was received late Monday afternoon.

Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, commander of the attack

The Attack

The battle

The first shots fired and the first casualties in the attack on Pearl Harbor actually occurred when the destroyer USS Ward attacked and sank a midget submarine at 06:37 Hawaiian Time during a routine patrol outside the Harbor entrance. Five Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines had been assigned to torpedo U.S. ships after the bombing started. None of these made it back safely, and only four out of the five have since been found. Of the ten sailors aboard the five submarines, nine died, and the only survivor, Kazuo Sakamaki, was captured, becoming the first prisoner of war captured by the Americans in World War II. United States Naval Institute photographic analysis conducted in 1999 indicates one midget submarine managed to enter the harbor and successfully fired a torpedo into the West Virginia. The final disposition of this submarine is unknown.

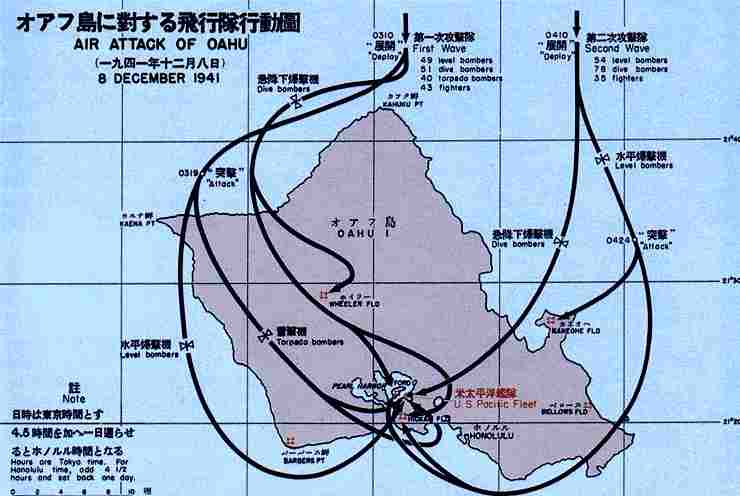

The two attack sorties of Imperial Japanese Navy approached from different directions. The U.S. radar which detected them 136 miles (218 km) away is at the top of this map

On the morning of the attack, the Army's Opana Point radar station detected the Japanese force, but the warning was confused by an untrained new officer at the only partially active Intelligence Center. Although the operators reported a sighting larger than anything they had ever seen, the officer assumed that the arrival of 6 U.S. B-17 bombers would account for such a sighting. Some commercial shipping may have reported "unusual" radio traffic, in the preceding days. Several U.S. aircraft were shot down as the air attack approached land; one, at least, radioed a somewhat incoherent warning. Other warnings were still being processed, or awaiting confirmation, when the shooting began. It is not clear that these forewarnings would have had any effect even if they had been interpreted perfectly. The results the Japanese achieved in the Philippines was essentially the same as at Pearl even though the Army Air Corps there had 10 hours of warning that the Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor.

The attack on Pearl Harbor began at 07:53 7 December Hawaiian Time, which was 03:23 AM December 8 Japanese Standard Time. Japanese planes attacked in two waves, in which a total of 353 planes reached Oahu. Vulnerable torpedo bombers led the first wave of 183 planes, exploiting the first moments of surprise by attacking the (hoped for) aircraft carriers and battleships while dive bombers attacked the U.S. air bases across Oahu, starting with Hickam Field, the largest, and Wheeler Air Field, the principal fighter base. The 170 planes of the second wave attacked Bellows Field and Ford Island, a marine and naval air base in the middle of Pearl Harbor. The only opposition came from some P-36 Hawks and P-40 Warhawks that flew 25 sorties and from naval anti-aircraft fire.

Wreck of a midget submarine

Men aboard U.S. ships awoke to the sounds of bombs exploding and cries of "Away fire and rescue party" and "All hands on deck, we're being bombed." Despite the lack of preparation, which included locked ammunition lockers, undispersed aircraft, and a lack of heightened alert status, there were many American military personnel who served with distinction during the battle. Rear Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, and Captain Franklin Van Valkenburgh, commander of the Arizona, both rushed to the bridge of Arizona and directed the ship's defense, until both were killed by an explosion in the forward ammunition magazine, caused by an armor-piercing bomb strike next to one of the forward main battery gun turrets. Both were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Ensign Joe Taussig got his ship, the Nevada, under way from a dead cold start during the attack. A destroyer got under way with only four officers onboard, all Ensigns, none of whom had more than a year's sea duty. That ship operated for four days at sea before its commanding officer caught up with it.

Captain Mervyn Bennion, commanding officer of the West Virginia, calmly led his men in battle until he was cut down by fragments from a bomb hit aboard the Tennessee, moored alongside. Earliest aircraft kill credit went to submarine the Tautog, which claimed the first attacker downed. Probably the most famous is Doris "Dorie" Miller, an African-American cook aboard the West Virginia, who went beyond the call of duty when he took control of an unattended anti-aircraft gun, on which he had no training, and used it to fire on the attacking planes, downing at least one, even while bombs were hitting his ship. He was awarded the Navy Cross. In all, 14 sailors and officers were awarded the Medal of Honor. A special military award, the Pearl Harbor Commemorative Medal, was later authorized to all military veterans of the attack.

Torpedo exploding into USS West Virginia, as seen from Japanese plane

Ninety minutes after it began, the attack was over. 2,403 Americans had lost their lives (of whom 68 were civilians, many killed by American anti-aircraft shells falling back to ground in civilian areas, including Honolulu), and a further 1,178 were wounded. Eighteen ships were sunk, including five battleships.

Nearly half of the American fatalities—1,102 men—were caused by the explosion and sinking of the Arizona. It was destroyed when a modified 40 cm naval gun shell, dropped from a bomber, smashed through its two armored decks and detonated the forward main gun magazine. The hull of the Arizona became a memorial to those lost that day, most of whom remain within the ship.

The Nevada attempted to exit the harbor, but was ordered to beach itself to avoid possibly blocking the harbor entrance. Already damaged by a torpedo and on fire forward, Nevada was targeted by many of Japan's bombers as it got underway. It sustained more hits from 250 lb (113 kg) bombs as it beached.

The California was hit by two bombs and two torpedoes. The crew might have kept her afloat if they had not been ordered to abandon ship just as they were raising power for the pumps. Burning oil from the Arizona and the West Virginia drifted down on her, and probably made the situation look worse than it was. The disarmed Utah was holed twice by torpedoes. The West Virginia was hit by seven torpedoes, the seventh tearing away the ship's rudder. The Oklahoma was hit by four torpedoes, the last two above its side armor belt which caused it to capsize. The Maryland was hit by two of the converted 40 cm shells, but neither caused serious damage.

Although the Japanese concentrated on battleships (the largest vessels present), they did not ignore other targets. The light cruiser Helena was torpedoed, and the concussion from the blast capsized the neighboring minelayer Oglala. Two destroyers in dry dock were destroyed when bombs penetrated their fuel bunkers. The leaking fuel caught fire and flooding the dry dock made the oil rise, which burned out the ships. The light cruiser Raleigh was hit by a torpedo and holed. The light cruiser Honolulu was damaged but remained in service. The destroyer USS Cassin capsized, and the Downes, also a destroyer, was heavily damaged. The repair vessel Vestal, moored alongside the Arizona at the time it exploded, was heavily damaged and was beached. The seaplane tender Curtiss was also damaged.

Almost every one of the 188 American aircraft were destroyed and 155 of those damaged were hit on the ground, where most had been parked wingtip to wingtip in central positions to minimize sabotage vulnerability. Attacks on barracks killed additional pilots and other personnel. Friendly fire brought down several planes. Fifty-five Japanese airmen and nine submariners were killed in the action. Of Japan's 441 available planes (350 took part in the attack), 29 were lost during the battle (nine in the first attack wave and 20 in the second wave) and another 74 were damaged by flak and machine gunfire from the ground. Over 20 of the aircraft that safely landed on their carriers could not be salvaged.

Pearl Harbor attack scene - Film trailer Youtube

Nagumo's decision to withdraw after two strikes

Some senior officers and flight leaders urged Nagumo to attack with a third strike to destroy the oil storage depots, machine shops, and dry docks at Pearl Harbor. The United States had considered the vulnerability of the fuel oil storage tanks before the war and secretly started construction of the bomb resistant Red Hill fuel tanks before Japan's attack. Destruction of these facilities would have greatly increased the U.S. Navy's difficulties, as the nearest immediately usable fleet facilities would have been several thousand miles east of Hawaii on America's West Coast. Some military historians have suggested that the destruction of oil tanks and repair facilities would have crippled the U.S. Pacific Fleet more seriously than the loss of several battleships. Nagumo decided to forgo a third attack in favor of withdrawing for several reasons:

Additional U.S. losses on 7 December 1941

The Japanese submarine I-26 sank the Cynthia Olson, a U.S. Army chartered schooner, off the coast of San Francisco with a loss of 35 lives.

Subsequent attacks

Later during the War several other, small-scale, attacks were also made on Pearl Harbor.

In March, 1942, in Operation K-1, a preparation for the Midway invasion, two Japanese H8K flying-boats, based at Wotje in the Marshall Islands, were tasked with reconnaissance to see how repairs were progressing, and to bomb the important "Ten-ten" repair dock. The distance involved required refueling en-route, and was done from submarines at French Frigate Shoals, 500 miles (800 km) north-west of Pearl Harbor. Poor visibility hampered the mission, and the bombs were dropped some miles from their target.

Five Japanese submarines supported the operation: I-9 as a radio beacon; I-19, I-15 and the I-26 to refuel the flying boats and I-23 to provide weather reports. However, the I-23 was lost without trace.

American ships were posted to the Shoals thereafter, which precluded another attempt using the same approach.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Declaration of War against Japan on the day following the attack

Immediate aftermath

American response

Ninety minutes before the attack on Pearl Harbor began (December 8, 1941 Japan time, on the other side of the international date line), Japan invaded British Malaya. This was followed by an early morning attack on the New Territories of Hong Kong and within hours or days by attacks on the Philippines, Wake Island, and Thailand and by the sinking of HMS Prince of Wales and Repulse.

On December 8, 1941, the U.S. Congress declared war on Japan, with Jeannette Rankin casting the only dissenting vote. The United States was outraged by the attack and by the late delivery of the note breaking off relations, actions which it considered treacherous. Roosevelt signed the declaration of war the same day, and called the previous day "a date which will live in infamy" in an address to a joint session of Congress. Continuing to intensify its military mobilization, the U.S. government began converting to a war economy.

The Pearl Harbor attack immediately galvanized a divided nation into action. Public opinion had been moving towards support for entering the War during 1941, but considerable opposition remained until the Pearl Harbor attack. Overnight, Americans united against Japan, and that response probably made possible the unconditional surrender position later taken by the Allied Powers. Some historians believe that the attack on Pearl Harbor doomed Japan to defeat simply because it awakened the "sleeping U.S. behemoth", regardless of whether the fuel depots or machine shops had been destroyed or even if the carriers had been caught in port and sunk. U.S. industrial and military capacity, once mobilized, was able to pour overwhelming resources into both the Pacific and Atlantic theaters.

Perceptions of treachery in the attack before a declaration of war sparked fears of sabotage or espionage by Japanese sympathizers residing in the US, including citizens of Japanese descent and was a factor in the subsequent Japanese internment in the western United States. Other factors included misrepresentations of intelligence information (none) suggesting sabotage, notably by General John DeWitt, commanding Coast Defense on the Pacific Coast, apparently because of personal bias. In February 1942, Roosevelt signed United States Executive Order 9066, requiring all Japanese Americans to submit themselves for arrest and internment.

Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy declared war on the United States on December 11, four days after the Japanese attack. Hitler and Mussolini were under no obligation to declare war under the mutual-defense terms of the Tripartite Pact. However, relations between the European Axis Powers and American leadership had gradually deteriorated since 1937. Earlier in 1941, the Nazis learned of the U.S. military's contingency planning to get troops in Continental Europe by 1943; this was the "Rainbow Five" plan and was made public by sources unsympathetic to Roosevelt's New Deal, notably the Chicago Tribune. Hitler seems to have decided that war with the United States was unavoidable, and the Pearl Harbor attack, the publication of the Rainbow Five plan, and Roosevelt's post-Pearl Harbor address, which focused on European affairs as well as the situation with Japan, probably contributed. Hitler also underestimated American military production capacity beyond Lend Lease, the nation's ability to fight on two fronts and the time Operation Barbarossa would require. Similarly, the Nazis may have hoped the declaration of war, a showing of solidarity with Japan, would result in closer collaboration with the Japanese in Eurasia. Regardless, the decision was an enormous strategic blunder and it enraged the American public. It allowed the United States to immediately enter the European theatre of war in support of the United Kingdom and the Allied camp without much public debate about the relative lack of retaliation against Japan. Conversely, the Pacific theatre became Japan's focus of attention; overwhelming the Americans—and later, defending against them—undermined cooperative efforts against British holdings from Southeast Asia to the Middle East. Opening a second front against the Soviet Union, which never came to fruition, also would have been of value to the combined Axis' war effort.

USS Utah took a torpedo hit and capsized early in the battle The wreck remains at Pearl Harbor

President Roosevelt appointed an investigating commission, headed by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts to report facts and findings with respect to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Both the Fleet commander, Rear Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, and the Army commander, Lieutenant General Walter Short (the Army Air Corps had been responsible for aerial defense of Hawaii, including Pearl Harbor, and for general defense of the islands against hostile attack), were relieved of their commands shortly thereafter. They were accused of 'dereliction of duty' by the Roberts Commission for not making reasonable defensive preparations. This evaluation has been controversial in some quarters ever since. On May 25, 1999, the Senate voted to recommend both officers be exonerated on all charges of dereliction of duty, citing allegations of the denial to Hawaii commanders of vital intelligence which was available in Washington.

In terms of its own objectives, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a tactical success which far exceeded the expectations of its planners. In execution, it has few parallels in the military history of any era. Even the surprise British carrier strike on the Italian's Taranto naval base in 1940 had not been so devastating in terms of damage inflicted, although in successfully neutralising the Italian navy it had much greater strategic implications. Due to its losses at Pearl Harbor and in the subsequent Japanese invasion of the Philippines, the U.S. Navy and Army Air Corps were unable to play any significant role in the Pacific War for the next six months. With the U.S. Pacific Fleet essentially out of the picture for the moment, Japan was temporarily free of worries about the rival Pacific naval power. It went on to conquer Southeast Asia, the Southwest Pacific, and to extend its reach far into the Indian Ocean.

Although Pearl Harbor was the most notable attack on American soil during WWII, there were several others (including the Philippine and Wake Island invasions.)

Japanese views of the attack

Imperial Japanese military leaders appear to have had mixed feelings about the attack. Yamamoto was unhappy about the botched timing of the breaking off of negotiations. He is commonly thought to have said, "I fear all we have done is awakened a sleeping giant and filled him with terrible resolve" . Even though the words may not have been uttered by Yamamoto, it did seem to capture his feelings about the attack. He is on record as saying, in the previous year, that "I can run wild for six months … after that, I have no expectation of success."

Although the Imperial Japanese government had made some effort to prepare the general Japanese civilian population for war with the U.S. through anti-U.S. propaganda, it appears that most Japanese were surprised, apprehensive, and dismayed by the news that they were now at war with the U.S., a country that many Japanese admired, and its allies. Nevertheless, the Japanese people living in Japan and its territories thereafter generally accepted their government's reasons for the attack and supported the war effort until their nation's surrender in 1945.

Japan's national leadership at that time appeared to believe that the war between the U.S. and Japan was inevitable. In 1942, Saburo Kurusu, former Japanese ambassador to the United States, gave an address in which he traced the "historical inevitability of the war of Greater East Asia." He said that the war was a response to Washington's longstanding aggression toward Japan. According to Kurusu, the provocations began with the San Francisco School incident and the United States' racist policies on Japanese immigrants, and culminated in the "belligerent" scrap metal and oil boycott by the United States and allied countries. Of Pearl Harbor itself, he said that it came in direct response to a virtual ultimatum, the Hull note, from the U.S. government, and that the surprise attack was not treacherous because it should have been expected.

Many Japanese today still feel that they were "pushed" into the war by the U.S. due to threats to their national security from the U.S. and other European powers or that the war "happened" to them through no fault of their own. For example, the Japan Times, an English-language newspaper owned by one of the major news organizations in Japan (Asahi Shimbun), ran a number of columns in the early 2000s that echo Kurusu's comments in reference to Pearl Harbor. Putting Pearl Harbor into context, writers repeatedly contrast the thousands of U.S. servicemen killed in that attack with the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians later killed by U.S. air attacks.

However, in spite of the perceived inevitability of the war, many Japanese believe that the Pearl Harbor attack, although a tactical victory, was in reality part of a seriously flawed strategy for engaging in war with the U.S. As one columnist eulogizes the attack:

In 1991, the Japanese Foreign Ministry released a statement saying that in 1941 Japan had intended to make a formal declaration of war to the United States at 1 PM Washington time, 25 minutes before the attacks at Pearl Harbor were scheduled to begin. It appears that the Japanese government was referring to the "14-part message", which did not even formally break off negotiations, let alone declare war. However, due to various delays, the Japanese ambassador was unable to make the declaration until well after the attacks had begun. The Japanese government apologized for this delay.

The first Prime Minister of Japan during World War II Hideki Tojo later wrote that:

Longer-term effects

A common view is that the Japan fell victim to victory disease due to the perceived ease of their first victories. Yet despite the perception of this battle as a devastating blow to America, only three ships were permanently lost to the U.S. Navy. These were the battleships Arizona, Oklahoma, and the old battleship Utah (then used as a target ship); nevertheless, much usable material was salvaged from them, including the two aft main turrets from Arizona. Heavy casualties resulted due to Arizona's magazine exploding and the Oklahoma capsizing. Four ships sunk during the attack were later raised and returned to duty, including the battleships California, West Virginia and Nevada. California and West Virginia had an effective torpedo-defense system which held up remarkably well, despite the weight of fire they had to endure, enabling most of their crews to be saved. Many of the surviving battleships were heavily refitted, including the replacement of their outdated secondary battery of anti-surface 5" guns with a more useful battery of turreted DP guns, allowing them to better cope with Japan's threats. The destroyers Cassin and Downes were constructive total losses, but their machinery was salvaged and fitted into new hulls, retaining their original names, while Shaw was raised and returned to service.

Of the 22 Japanese ships that took part in the attack, only one survived the war. As of 2006, the only U.S. ship still afloat that was in Pearl Harbor during the attack is the Coast Guard Cutter Taney.

In the long term, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a strategic blunder for Japan. Indeed, Admiral Yamamoto, who devised the Pearl Harbor attack, had predicted that even a successful attack on the U.S. Fleet could not win a war with the United States, because American productive capacity was too large. One of the main Japanese objectives was to destroy the three American aircraft carriers stationed in the Pacific, but they were not present: Enterprise was returning from Wake Island, Lexington was near Midway Island, and Saratoga was in San Diego following a refit at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Putting most of the U.S. battleships out of commission was regarded—in both Navies and by most observers worldwide—as a tremendous success for Japan.

Though the attack was notable for large-scale destruction, the attack was not significant in terms of long-term loss. Had Japan destroyed the American carriers, the U.S. might have sustained significant damage to its Pacific Fleet for a year or so. As it was, the elimination of the battleships left the U.S. Navy with no choice but to put its faith in aircraft carriers and submarines—and these were the tools with which the U.S. Navy would halt and eventually reverse the Japanese advance. One particular flaw of Japanese strategic thinking was that the ultimate Pacific battle would be between battleships of both sides. As a result, Yamamoto hoarded his battleships for a decisive battle that would never happen.

Ultimately, targets that never made the list, the Submarine Base and the old Headquarters Building, were more important than any of them. It was submarines that brought Japan's economy to a standstill and crippled its transportation of oil, immobilizing heavy ships. And in the basement of the old Headquarters Building was the cryptanalytic unit, Station Hypo.

Historical significance

This battle has had history-altering consequences. It only had a small strategic military effect due to the failure of the Japanese Navy to sink U.S. aircraft carriers, but even if the air carriers had been sunk, it may not have helped Japan in the long term. The attack firmly drew the United States and its massive industrial and service economy into World War II, and the U.S. sent huge numbers of soldiers and a great amount of weapons and supplies to help the Allies fight Germany, Italy, and Japan, contributing to the utter defeat of the Axis powers by 1945. It also resulted in Germany declaring war on the United States four days later.

The United Kingdom's Prime Minister Winston Churchill, on hearing that the attack on Pearl Harbor had finally drawn the United States into the war, wrote: "Being saturated and satiated with emotion and sensation, I went to bed and slept the sleep of the saved and thankful." The Allied victory in this war and the subsequent U.S. emergence as a dominant world power have shaped international politics ever since.

In terms of military history, the attack on Pearl Harbor marked the emergence of the aircraft carrier as the center of naval power, replacing the battleship as the keystone of the fleet. However, it was not until later battles, notably the Coral Sea and Midway, that this breakthrough became apparent to the world's naval powers.

Mythical status

Pearl Harbor is a major event in American history marking the first time since the War of 1812 America was attacked on its home soil by another country. The event has assumed mythical status, and its prominence was vividly demonstrated sixty years later when the September 11, 2001 attacks took place: the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks were instantly compared to Pearl Harbor.

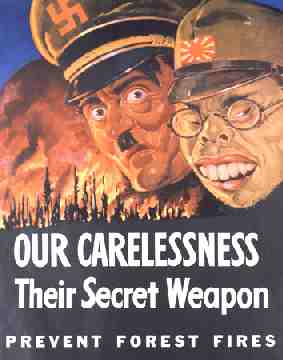

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the U.S. peaked during World War II. The government subsidized the production of propaganda posters using racial stereotypes. Shown here Adolf Hitler and Hideki Tojo of the Axis alliance

Cultural impact

The attack on Pearl Harbor and the ensuing war in the Pacific, fueled anti-Japanese sentiment. Japanese, Japanese-Americans and Asians having a similar physical appearance were regarded with suspicion, distrust and hostility. The attack was viewed as having been conducted in an underhanded way and also as a very "treacherous" or "sneaky attack". The fear of a Japanese-American Fifth column led to the massive arrest of this ethnic population since February 19, 1942 and its resulting Japanese American internment, a modest term to designate taboo "concentration camps", in both the United States and Canada.

The attacks on Pearl Harbor were depicted in the joint American-Japanese film Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), the American film Pearl Harbor (2001) and in several Japanese productions.

Recipients of the Medal of Honor* Awarded posthumously.

LINKS and REFERENCE

Further reading

GENERAL HISTORY LINKS

MARITIME HISTORY

|

|

|

This website is copyright © 1991- 2013 Electrick Publications. All rights reserved. The bird logo and names Solar Navigator and Blueplanet Ecostar are trademarks ™. The Blueplanet vehicle configuration is registered ®. All other trademarks hereby acknowledged and please note that this project should not be confused with the Australian: 'World Solar Challenge'™which is a superb road vehicle endurance race from Darwin to Adelaide. Max Energy Limited is an educational charity working hard to promote world peace.

|