|

NAIROBI

DECEMBER 19 2012 (Reuters)

A dozen soldiers guarding a North Korean ship impounded in Somalia's autonomous Puntland region for maritime violations have hijacked the vessel

they were guarding and its 33 crew, government and naval sources said on Wednesday.

Puntland had been the epicenter of Somali piracy but the use of armed guards on ships and a concerted crackdown by international navies has seen the number of successful pirate hijackings fall in 2012.

MV Daesan, a North Korean ship ferrying cement to Somali capital Mogadishu, was impounded and fined last month by Puntland authorities who accused it of ditching its cargo off Somalia's coast.

The ship dumped the cement into the ocean because it had been rejected by importers in Mogadishu, who claimed that the cement was wet and unusable, authorities said.

However, a government source told Reuters a dozen soldiers guarding the vessel hijacked it on Tuesday night. It was now at sea, destination unknown.

A naval source at the port of Bosasso, near where the ship lay seized over the past month, confirmed the claim.

"The government is preparing troops to rescue the ship," the naval source said.

In 2005, Puntland's naval forces hijacked a Thai fishing boat and demanded an $800,000 ransom for its release, according to Jay Bahadur, a Canadian author of a book on Somali piracy.

About 136 hostages taken in the Indian Ocean off Somalia are still being held captive, but the number of hijackings of ships has dropped to seven in the first 11 months of this year compared to 24 in the whole of 2011.

Drazen

Jorgic James Macharia and Michael Roddy -

Somalia - Soldiers hijack North Korean ship

TUESDAY

4 DECEMBER 2012 - S. Korea Ship Counter-piracy Measures Introduced

A law revision requires South Korean ships to build safe areas (citadels) against pirate attacks.

The recent revision, passed in the National Assembly on Nov. 22, 2012, obliges the construction of a so-called "citadel" inside ships that have to sail through international waters reports the Yonhap News Agency.

When the revision will go into effect is not yet known, but it is expected to come into force soon.

Previously there had been no related laws requiring owners to provide such safe areas, crew members have been left vulnerable to pirate attacks.

There have been a total of nine cases where South Korean sailors were kidnapped in waters off Somalia since 2006. Six of the cases involved Korean ships, while two were

Japanese and one was Singaporean.

A source in the South Korean government informed

the Yonhap News Agency that it also plans to make it mandatory for security guards to be aboard ships sailing through dangerous areas.

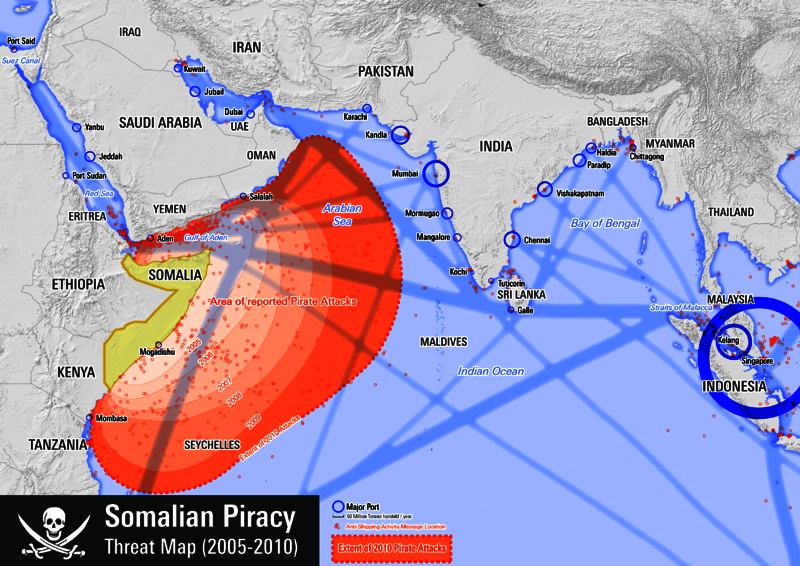

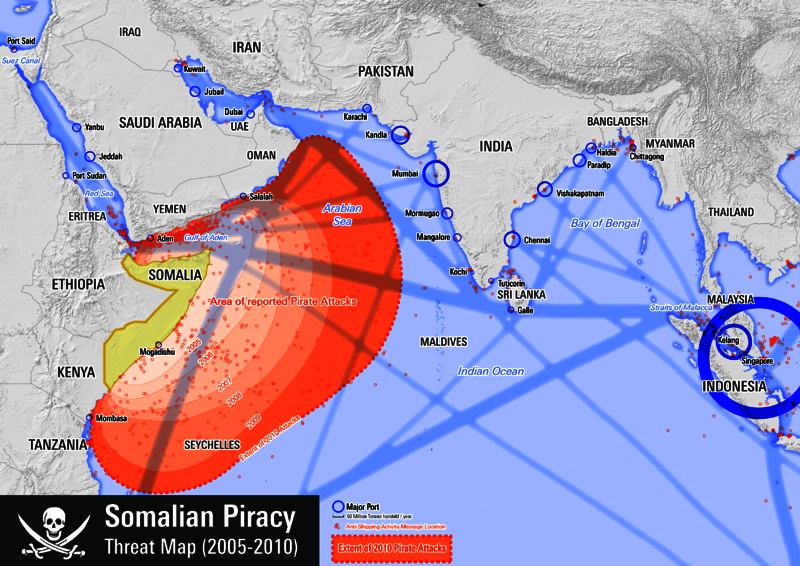

OVERVIEW

Piracy off the coast of Somalia has been a threat to international shipping since the second phase of the Somali Civil War in the early 21st

century. Since 2005, many international organizations, including the International Maritime Organization and the World Food Programme, have expressed concern over the rise in acts of

piracy. Piracy has impeded the delivery of shipments and increased shipping expenses, costing an estimated $6.6 to $6.9 billion a year in global trade per Oceans Beyond Piracy

(OBP). According to the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), a veritable industry of profiteers has also risen around the piracy. Insurance companies, in particular, have profited from the pirate attacks, as insurance premiums have increased

significantly.

A United Nations report and several news sources have suggested that piracy off the coast of Somalia is caused in part by illegal

fishing. According to the DIW and the U.S. House Armed Services Committee, the dumping of toxic waste in Somali waters by foreign vessels has also severely constrained the ability of local fishermen to earn a living and forced many to turn to piracy

instead. 70 percent of the local coastal communities "strongly support the piracy as a form of national defense of the country's territorial waters", and the pirates believe they are protecting their fishing grounds and exacting justice and compensation for the marine resources

stolen. Some reports have suggested that, in the absence of an effective national coast guard following the outbreak of the civil war and the subsequent disintegration of the Armed Forces, local fishermen formed organized groups in order to protect their waters. This motivation is reflected in the names taken on by some of the pirate networks, such as the National Volunteer Coast

Guard. However, as piracy has become substantially more lucrative in recent years, other reports have speculated that financial gain is now the primary motive for the

pirates.

Combined Task Force 150, a multinational coalition task force, took on the role of fighting piracy off of the coast of Somalia by establishing a Maritime Security Patrol Area (MSPA) within the Gulf of Aden.[16] The increasing threat posed by piracy has also caused concern in India since most of its shipping trade routes pass through the Gulf of Aden. The Indian Navy responded to these concerns by deploying a warship in the region on 23 October 2008. In September 2008, Russia announced that it too would join international efforts to combat

piracy. Some reports have also accused certain government officials in Somalia of complicity with the

pirates, with authorities from the Galmudug administration in the north-central Hobyo district reportedly attempting to use pirate gangs as a bulwark against Islamist insurgents from the nation's southern conflict

zones. However, according to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon, both the former and current administrations of the autonomous Puntland region in northeastern Somalia appear to be more actively involved in combating

piracy. The latter measures include on-land raids on pirate

hideouts, and the construction of a new naval base in conjunction with Saracen International, a UK-based security

company. By the first half of 2010, these increased policing efforts by Somali government authorities on land and international naval vessels at sea reportedly contributed to a drop in pirate attacks in the Gulf of Aden from 86 a year prior to 33, forcing pirates to shift attention to other areas such as the Somali Basin and the wider Indian

Ocean. By the end of 2011, pirates managed to seize only four ships off of the coast of Somalia; 18 fewer than the 26 they had captured in each of the two previous years. They also attempted unsuccessful attacks on 52 other vessels, 16 fewer than the year

prior. As of 3 December 2012, the pirates were holding approximately 5 large ships with an estimated 136

hostages.

According to another source, there were 151 attacks on ships in 2011, compared to 127 in 2010 - but only 25 successful hijacks compared to 47 in 2010. 10 vessels and 159 hostages were being held at February 2012. In 2011, pirates earned $146m, an average of $4.87m per ship. An estimated 3,000 to 5,000 pirates operated; by February 2012 1,000 had been captured and were going through legal processes in 21

countries. According to the European Union Naval Force (EU NAVFOR), intensified naval operations had by February 2012 led to a further drop in successful pirate attacks in the Indian Ocean, with the pirates' movements in the region at large also significantly

constrained. 25 military vessels from the EU and Nato countries, the USA, China, Russia, India and Japan patrolled approximately 8.3m km2 (3.2m sq miles) of ocean, an area about the size of Western

Europe. On 16 July 2012, the European Union launched a new operation, EUCAP Nestor. An analysis by the Brussels-based Global Governance Institute urged the EU to commit onshore to prevent

piracy. By September 2012, the heyday of piracy in the Indian Ocean was reportedly over. Backers were now reportedly reluctant to finance pirate expeditions due to the low rate of success, and pirates were no longer able to reimburse their

creditors. According to the International Maritime Bureau, pirate attacks had by October 2012 dropped to a six-year low, with only 1 ship attacked in the third quarter compared to 36 during the same period in

2011.

HISTORY

In the early 1980s, prior to the outbreak of the civil war in Somalia, the

Somali Ministry of Fisheries and the Coastal Development Agency (CDA) launched a development program focusing on the establishment of agricultural and fishery cooperatives for artisinal fishermen. It also received significant foreign investment funds for various fishery development projects, as the Somali fishing industry was considered to have a lot of potential owing to its unexploited marine stocks. The government at this time permitted foreign fishing through official licensing or joint venture agreements, forming two such partnerships in the Iraqi-Somali Siadco and Italian-Somali Somital ventures.

After the collapse of the central government in the ensuing civil war, the Somali Navy disbanded. With Somali territorial waters undefended, foreign fishing trawlers began illegally fishing on the Somali seaboard and ships from big companies started dumping waste off the coast of Somalia. This led to the erosion of the fish stock. Local fishermen subsequently started to band together to protect their resources. After seeing the profitability of ransom payments, some financiers and former militiamen later began to fund pirate activities, splitting the profits evenly with the pirates. In most of the hijackings, the pirates have not harmed their prisoners.

Combined Task Force 150, a multinational coalition task force, subsequently took on the role of fighting piracy off the coast of Somalia by establishing a Maritime Security Patrol Area (MSPA) within the Gulf of Aden. However, many foreign naval vessels chasing pirates were forced to break off when the pirates entered Somali territorial waters. To address this, in June 2008, following a letter from the Somalian Transitional Federal Government (TFG) to the President of the UN Security Council requesting assistance for the TFG's efforts to tackle acts of piracy off the coast of Somalia, the UN Security Council unanimously passed a declaration authorizing nations that have the consent of the Transitional Federal Government to enter Somali territorial waters to deal with pirates. On the advice of lawyers, the

Royal Navy and other international

naval forces have often released suspected pirates that they have captured because, although the men are frequently armed, they have not been caught engaging in acts of piracy and have thus not technically committed a crime.

Due to improved anti-piracy measures the success of piracy acts on sea decreased dramatically by the end of 2011 with only four vessels hijacked in the last quarter versus 17 in the last quarter of the preceding year. In response, pirates resorted to increased hostage taking on land. The government of the autonomous Puntland region has also made progress in combating piracy, evident in recent interventions by its maritime police force (PMPF).

In part to further curtail piracy activity, the London Somalia Conference was also convened in February 2012.

Summary of recent events

Somali pirates have attacked hundreds of vessels in the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean region, though most attacks do not result in a successful hijacking. In 2008, there were 111 attacks which included 42 successful hijackings. However, this is only a fraction of the up to 30,000 merchant vessels which pass through that area. The rate of attacks in January and February 2009 was about 10 times higher than during the same period in 2008 and "there have been almost daily attacks in March", with 79 attacks, 21 successful, by mid April. Most of these attacks occur in the Gulf of Aden but the Somali pirates have been increasing their range and have started attacking ships as far south as off the coast of Kenya in the Indian Ocean. Below are some notable pirate events which have garnered significant media coverage since 2007.

On 28 May 2007, a Chinese sailor was killed by the pirates because the ship's owners failed to meet their ransom demand.

On 5 October 2008, the United Nations Security Council adopted resolution 1838 calling on nations with vessels in the area to apply military force to repress the acts of piracy. At the 101st council of the International Maritime Organization, India called for a United Nations peacekeeping force under unified command to tackle piracy off Somalia. (There has been a general and complete arms embargo against Somalia since 1992.)

In November 2008, Somali pirates began hijacking ships well outside the Gulf of Aden, perhaps targeting ships headed for the port of

Mombasa, Kenya.] The frequency and sophistication of the attacks also increased around this time, as did the size of vessels being targeted. Large cargo ships, oil and chemical tankers on international voyages became the new targets of choice for the Somali hijackers. This is in stark contrast to the pirate attacks which were once frequent in the Strait of Malacca, another strategically important waterway for international trade, which were according to maritime security expert Catherine Zara Raymond, generally directed against "smaller, more vulnerable vessels carrying trade across the Straits or employed in the coastal trade on either side of the Straits."

On 19 November 2008, the Indian Navy warship INS Tabar sank a suspected pirate mothership. Later, it was claimed to be a Thai trawler being hijacked by

pirates. The Indian Navy later defended its actions by stating that they were fired upon first.

On 21 November 2008, BBC News reported that the Indian Navy had received United Nations approval to enter Somali waters to combat piracy.

On 8 April 2009, four Somali pirates seized the Maersk Alabama 240 nautical miles (440 km; 280 mi) southeast of the Somalia port city of Eyl. The ship was carrying 17,000 metric tons of cargo, of which 5,000 metric tons were relief supplies bound for Somalia, Uganda, and

Kenya. On 12 April 2009, United States Navy SEAL snipers killed the three pirates that were holding Captain Richard Phillips hostage aboard a lifeboat from the Maersk Alabama after determining that Captain Phillips' life was in immediate danger. A fourth pirate, Abdul Wali Muse, surrendered and was taken into custody. On May 18, a federal grand jury in New York returned a ten-count indictment against him.

On 20 April 2009, United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton commented on the capture and release of 7 Somali pirates by Dutch Naval forces who were on a NATO mission. After an attack on the Handytankers Magic, a petroleum tanker, the Dutch frigate De Zeven Provinciën tracked the pirates back to a pirate "mother ship" and captured them. They confiscated the pirates' weapons and freed 20 Yemeni fishermen whom the pirates had kidnapped and who had been forced to sail the pirate "mother ship". Since the Dutch Naval Forces were part of a

NATO exercise, but not on an EU mission, they lacked legal jurisdiction to keep the pirates so they released them. Clinton stated that this action "sends the wrong signal" and that additional coordination was needed among nations.

On 23 April 2009, international donors pledged over $250 million for Somalia, including $134 million to increase the African Union peacekeeping mission from 4,350 troops to 8,000 troops and $34 million for Somali security forces. Secretary-General of the United Nations Ban Ki-moon told delegates at a donors' conference sponsored by the U.N. that "Piracy is a symptom of anarchy and insecurity on the ground", and that "More security on the ground will make less piracy on the seas." Somali President Sharif Ahmed pledged at the conference that he would fight piracy and to loud applause said that "It is our duty to pursue these criminals not only on the high seas, but also on terra firma". The Somali government has not gone after pirates because pirate leaders currently have more power than the government. It has been estimated by piracy experts that in 2008 the pirates gained about $80 million through ransom payments.

On 2 May 2009, Somali pirates captured the MV Ariana with its 24 Ukrainian

crew. The ship was released on 10 December 2009 after a ransom of almost $3,000,000 was paid.

On 8 November 2009, Somali pirates threatened that a kidnapped British couple, the Chandlers, would be "punished" if a German warship did not release seven pirates. Omer, one of the pirates holding the British couple, claimed the seven men were fishermen, but a

European Union Naval Force spokesman stated they were captured as they fired AK-47 assault rifles at a

French fishing vessel. The Chandlers were released on 14 November 2010 after 388 days of captivity. At least two ransom payments, reportedly over GBP 500 000, had been made.

In April 2010, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) alluded to possible covert and overt action against the pirates. CIA officials had been publicly warning of this potential threat for months. In a Harpers Magazine article, a CIA official said, "We need to deal with this problem from the beach side, in concert with the ocean side, but we don't have an embassy in Somalia and limited, ineffective intelligence operations. We need to work in Somalia and in Lebanon, where a lot of the ransom money has changed hands. But our operations in Lebanon are a joke, and we have no presence at all in Somalia."

In early May 2010, Russian special forces retook a

Russian oil tanker that had been hijacked by 11 pirates. One died in the assault, and a week later Russian military officials reported that the remainder were freed due to weaknesses in international law but died before reaching the Somali coast. Russian President Dmitry Medvedev had announced the day the ship was retaken that "We'll have to do what our forefathers did when they met the pirates" until a suitable way of prosecuting them was available.

On 11 May 2010 Somali pirates seized a Bulgarian-flagged ship in the Gulf of Aden. The Panega, with 15 Bulgarian crew members aboard, was en route from the Red Sea to India or

Pakistan. This was the first such hijacking of a Bulgarian-flagged ship. On 12 May 2010, Athens announced that Somali pirates have seized a Greek vessel in the Gulf of Aden with at least 24 people on board, including two Greek citizens and some Filipinos. The vessel, sailing under the Liberian flag, was transporting iron from Ukraine to

China.

On 14 January 2011, while speaking to reporters, Commodore Michiel Hijmans of the Royal Netherlands Navy stated that the use of hijacked vessels in more recent hijackings had led to increased range of pirating activities, as well as difficulty to actively thwart future events due to the use of kidnapped sailors as human shields.

On 15 January 2011 thirteen Somali pirates seized the Samho Jewelry, a

Maltese-flagged chemical carrier operated by Samho Shipping, 650 km southeast of Muscat. The Republic of Korea Navy destroyer Choi Young shadowed the Samho Jewlry for several days. In the early morning of 21 January 2011, 25 ROK Navy

SEALs on small boats launched from the Choi Young boarded the Samho Jewelry while the Choi Youngs Westland Super Lynx provided covering fire. Eight pirates were killed and five captured in the operation; the crew of 21 was freed with the Captain suffering a gunshot wound to the stomach.

On 28 January 2011, an Indian Coast Guard aircraft while responding to a distress call from the CMA CGM Verdi, located two skiffs attempting a piracy attack near Lakshadweep. Seeing the aircraft, the skiffs immediately aborted their piracy attempt and dashed towards the mother vessel, MV Prantalay 14 – a hijacked Thai trawler, which hurriedly hoisted the two skiffs on board and moved westward. The Indian Navy deployed the INS Cankarso which located and engaged the mothership 100 nautical miles north of the Minicoy island. 10 pirates were killed while 15 were apprehended and 20 Thai and Burmese fishermen being held aboard the ship as hostages were

rescued.

Within a week of its previous success, the Indian Navy captured another hijacked Thai trawler, MV Prantalay 11 and captured 28 pirates aboard in an operation undertaken by the INS Tir purusuant to receiving information that a Greek merchant ship had been attacked by pirates on board high-speed boats, although it had managed to avoid capture. When INS Tir ordered the pirate ship to stop and be boarded for inspection, it was fired upon. The INS Tir returned fire in which 3 pirates were injured and caused the pirates to raise a white flag indicating their surrender. The INS Tir subsequently joined by CGS Samar of the Indian Coast Guard. Officials from the Indian Navy reported that a total of 52 men were apprehended, but that 24 are suspected to be Thai fishermen who were hostages of the 28 African pirates.

In late February 2011, piracy targeting smaller yachts and collecting ransom made headlines when four Americans were killed aboard their vessel, the Quest, by their captors, while a military ship shadowed them. A federal court in Norfolk, Virginia, sentenced three members of the gang that seized the yacht to life imprisonment. On 24 February 2011 a Danish family on a yacht were captured by pirates.

In March 2011, the Indian Navy intercepted a pirate mother vessel 600 nautical miles west of the Indian coast in the Arabian Sea on Monday and rescued 13 hostages. Sixty-one pirates have also been caught in the operation carried out by Navy's INS Kalpeni.

In late March 2011, Indian Navy seized 16 suspected pirates after a three-hour-long battle in the Arabian Sea, The navy also rescued 16 crew members of a hijacked Iranian ship west of the Lakshadweep Islands. The crew included 12 Iranians and four Pakistanis.

On Jan. 5 2012, an SH-60S Seahawk from the guided-missile destroyer USS Kidd, part of the USS John C. Stennis Carrier Strike Group, detected a suspected pirate skiff alongside the Iranian-flagged fishing boat, Al Molai. The master of the Al Molai sent a distress call about the same time reporting pirates were holding him captive.

A visit, board, search and seizure team from the Kidd boarded the dhow, a traditional Arabian sailing vessel, and detained 15 suspected pirates who had been holding a 13-member Iranian crew hostage for several weeks. The Al Molai had been pirated and used as a "mother ship" for pirate operations throughout the Persian Gulf, members of the Iranian vessel's crew reported.

Pirates - Profile

Most of the pirates are youngsters. An official list issued in 2010 by the Somali government of 40 apprehended pirate suspects noted that 80% (32/40) were born in Somalia's southern conflict zones, while only 20% (8/40) came from the more stable northern regions. As of 2012, the pirates primarily operate from the Galmudug region in the central section of the country. In previous years, they largely ventured into sea from ports in the northeastern Puntland province, until the regional administration launched a major anti-piracy campaign and established a maritime police force (PMPF).

According to a 2008 BBC report, the pirates can be divided into three main categories:

Local fishermen, considered the brains of the pirates' operations due to their skill and knowledge of the sea. Many think that foreign boats have no right to cruise next to the shore and destroy their boats.

Ex-militiamen, who previously fought for the local clan warlords, or ex-military from the former Barre government used as the muscle.

Technical experts, who operate equipment such as GPS devices.

The closest Somali term for 'pirate' is burcad badeed, which means "ocean robber". However, the pirates themselves prefer to be called badaadinta badah or "saviours of the sea" (often translated as "coastguard").

Methodology

The methods used in a typical pirate attack have been analyzed. They show that while attacks can be expected at any time, most occur during the day, often in the early hours. They may involve two or more skiffs that can reach speeds of up to 25 knots. With the help of motherships that include captured fishing and merchant vessels the operating range of the skiffs has been increased far into the Indian Ocean. An attacked vessel is approached from quarter or stern; RPGs and small arms are used to intimidate the operator to slow down and allow boarding. Light ladders are brought along to climb aboard. Pirates then will try and get control of the bridge to take operational control of the vessel. According to Sky News, pirates also often jettison their equipment in the sea before being arrested, as this lowers the likelihood of a successful prosecution.

Weaponry and funding

The pirates get most of their weapons from Yemen, but a significant amount comes from Mogadishu, Somalia's capital. Weapons dealers in the capital receive a deposit from a hawala dealer on behalf of the pirates and the weapons are then driven to Puntland where the pirates pay the balance. Various photographs of pirates in situ indicate that their weapons are predominantly AKMs, RPG-7s, AK47s, and semi-automatic pistols such as the TT-30. Additionally, given the particular origin of their weaponry, they are likely to have hand grenades such as the RGD-5 or F1.

The funding of piracy operations is now structured in a stock exchange, with investors buying and selling shares in upcoming attacks in a bourse in Harardhere. Pirates say ransom money is paid in large denomination US dollar bills. It is delivered to them in burlap sacks which are either dropped from helicopters or cased in waterproof suitcases loaded onto tiny skiffs. Ransom money has also been delivered to pirates via parachute, as happened in January 2009 when an orange container with $3 million cash inside was dropped onto the deck of the supertanker MV Sirius Star to secure the release of ship and

crew. To authenticate the banknotes, pirates use currency-counting machines, the same technology used at foreign exchange bureaus worldwide. According to one pirate, these machines are, in turn, purchased from business connections in Dubai, Djibouti, and other

areas. Hostages seized by the pirates usually have to wait 45 days or more for the ships' owners to pay the ransom and secure their release.

In 2008, there were also allegations that the pirates received assistance from some members of the Somali diaspora. Somali expatriates, including some members of the Somali community in Canada, reputedly offered funds, equipment and information.

According to the head of the U.N.'s counter-piracy division, Colonel John Steed, the Al-Shabaab group in 2011 increasingly sought to cooperate with the pirate gangs in the face of dwindling funds and resources for their own activities. Steed, however, acknowledged that he had no definite proof of operational ties between the pirates and the Islamist militants. Detained pirates also indicated to UNODC officials that some measure of cooperation with Al-Shabaab militants was necessary, as they have increasingly launched maritime raids from areas in southern Somalia controlled by the insurgent outfit. Al-Shabaab members have also extorted the pirates, demanding protection money from them and forcing seized pirate gang leaders in Harardhere to hand over 20% of future ransom proceeds. There have also been ties with al-Qaeda receiving funding from pirate operations. A maritime intelligence source told CBS News that it was "‘inconceivable’ to Western intelligence agencies that al Qaeda would not be getting some financial reward from the successful hijackings." They go on to express concern about this funding link being able to keep the group satisfied as piracy gains more publicity and higher ransoms.

Effects and perceptions - Costs

Both positive and negative effects of piracy have been

reported. In 2009, pirate income derived from ransoms was estimated at around 39 million euros (about $58

million), rising to $238 million in 2010. The average ransom had risen to $5.4 million in 2010, up from around $150 thousand in 2005. However, by 2011, pirate ransom income dropped to $160 million, a downward trend which has been attributed to intensified counter-piracy efforts.

Besides the actual cost of paying ransoms, various attempts have been made at gauging indirect costs stemming from the piracy; especially those reportedly incurred over the course of anti-piracy initiatives.

During the height of the piracy phenomenon in 2008, local residents complained that the presence of so many armed men made them feel insecure and that their free spending ways caused wild fluctuations in the local exchange rate. Others faulted them for excessive consumption of alcoholic beverages and khat.

A 2010 report suggested that piracy off the coast of Somalia lead to a decrease of revenue for Egypt as fewer ships use the Suez canal (estimated loss of about $642 million), impeded trade with neighboring countries, and negatively impacted tourism and fishing in the Seychelles. According to Sky News, around 50% of the world's containers passed through the Horn of Africa coastline as of 2012. The European Union Naval Force (EU NAVFOR) has a yearly budget of over 8 million Euros earmarked for patrolling the 3.2 million square miles.

A 2011 report by Oceans Beyond Piracy (OBP) suggested that the indirect costs of piracy were much higher and estimated to be between $6.6 to $6.9 billion, as they also included insurance, naval support, legal proceedings, re-routing of slower ships, and individual protective steps taken by ship-owners.

Another report from 2011 published by the consultancy firm Geopolicity Inc. investigated the causes and consequences of international piracy, with a particular focus on such activity off the coast of Somalia. The paper asserted that what began as an attempt in the mid-1990s by Somali fishermen to protect their territorial waters has extended far beyond their seaboard and grown into an emerging market in its own right. Due to potentially substantial financial rewards, the report hypothesized that the number of new pirates could swell by 400 persons annually, that pirate ransom income could in turn rise to $400 million per year by 2015, and that piracy costs as a whole could increase to $15 billion over the same period.

According to a 2012 investigative piece by the Somalia Report, the OBP paper and other similar reports that attempt to calibrate the global cost of piracy produce inaccurate estimates based on a variety of factors. Most saliently, instead of comparing the actual costs of piracy with the considerable benefits derived from the phenomenon by the maritime industry and local parties capitalizing on capacity-building initiatives, the OBP paper conflated the alleged piracy costs with the large premiums made by insurance companies and lumped them together with governmental and societal costs. The report also exaggerated the impact that piracy has had on the shipping sector, an industry which has grown steadily in size from 25,000 billion tonnes/miles to 35,000 billion tonnes/miles since the rise of Indian Ocean piracy in 2005.

Moreover, the global costs of piracy reportedly represent a small fraction of total maritime shipping expenses and are significantly lower than more routine costs, such as those brought on by port theft, bad weather conditions or fuel-related issues. In the United States alone, the National Cargo Security Council estimated that between $10–$15 billion were stolen from ports in 2003, a figure several times higher than the projected global cost of piracy. Additionally, while the OBP paper alleged that pirate activity has had a significantly negative impact on regional economies, particularly the Kenyan tourism industry, tourist-derived revenue in Kenya rose by 32% in 2011. According to the Somalia Report investigation, the OBP paper also did not factor into its calculations the overall decline in successful pirate attacks beginning in the second half of 2011, a downward trend largely brought about by the increasing use of armed guards.

Benefits

Some benefits from the piracy have also been noted. In the earlier years of the phenomenon in 2008, it was reported that many local residents in pirate hubs such as Harardhere appreciated the rejuvenating effect that the pirates' on-shore spending and restocking had on their small towns, a presence which often provided jobs and opportunity when there were comparatively fewer. Entire hamlets were in the process reportedly transformed into boomtowns, with local shop owners and other residents using their gains to purchase items such as generators for uninterrupted electricity. However, the election of a new administration in 2009 in the northeastern Puntland region saw a sharp decrease in pirate operations, as the provincial authorities launched a comprehensive anti-piracy campaign and established an official maritime police force (PMPF). Since 2010, pirates have mainly operated from the Galmudug region to the south. According to the Somalia Report, the significant infrastructural development evident in Puntland's urban centers has also mainly come from a combination of government development programs, internal investment by local residents returning to their home regions following the civil war in the south, and especially remittance funds sent by the sizable Somali diaspora. The latter contributions have been estimated at around $1.3-$2 billion a year, exponentially dwarfing pirate ransom proceeds, which total only a few million dollars annually and are difficult to track in terms of spending.

Additionally, impoverished fishermen in Kenya's Malindi area in the southeastern African Great Lakes region have reported their largest catches in forty years, catching hundreds of kilos of fish and earning fifty times the average daily wage as a result. They attribute the recent abundance and variety of marine stock to the pirates scaring away predatory foreign fishing trawlers, which have for decades deprived local dhows of a livelihood. According to marine biologists, indicators are that the local fishery is recovering because of the lack of commercial scale fishing.

Piracy off the coast of Somalia also appears to have a positive impact on the problem of overfishing in Somali waters by foreign vessels. A comparison has been made with the situation in Tanzania further to the south, which is also affected by predatory fishing by foreign ships and generally lacks the means to effectively protect and regulate its territorial waters. There, catches have dropped to dramatically low levels, whereas in Somalia they have risen back to more acceptable levels since the beginning of the piracy.

Casualties

Piracy off of the coast of Somalia has reportedly produced some casualties. According to many interviewed maritime security firms, ship owner groups, lawyers and insurance companies, fear of pirate attacks has increased the likelihood of violent encounters at sea, as untrained or overeager vessel guards have resorted to shooting indiscriminately without first properly assessing the actual threat level. In the process, they have killed both pirates and sometimes innocent fishermen as well as jeopardized the reputation of private maritime security firms with their reckless gun use. Since many of the new maritime security companies that have emerged often also enlist the services of off-duty policemen and former soldiers that saw combat in Iraq and Afghanistan, worries of a "Blackwater out in the Indian Ocean" have only intensified.

Of the 4,185 seafarers whose ships had been attacked by the pirates and the 1,090 who were held hostage in 2010, a third were reportedly abused. Some captives have also indicated that they were used as human shields for pirate attacks while being held hostage.

According to Reuters, of the 3,500 captured during a four-year period, 62 died. The causes of death included suicide and malnutrition, with 25 of the deaths attributed to murder according to Intercargo. In some cases, the captives have also reported being tortured. Many seafarers are also left traumatized after release.

Profiteers

According to the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), a veritable industry of profiteers has also risen around the piracy. Insurance companies, in particular, have profited from the pirate attacks, as insurance premiums have increased significantly. DIW reports that, in order to keep premiums high, insurance firms have not demanded that ship owners take security precautions that would make hijackings more difficult. For their part, shipping companies often do not comply with naval guidelines on how best to prevent pirate attacks in order to cut down on costs. Ship crews have also been reluctant to repel the pirates on account of their low wages and inequitable work contracts. In addition, security contractors and the German arms industry have profited from the phenomenon.

Sovereignty and environmental protection

The former UN envoy for Somalia, Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, has stated that "because there is no (effective) government, there is ... much irregular fishing from European and Asian countries," and that the UN has what he described as "reliable information" that European and Asian companies are dumping toxic and nuclear waste off the Somali coastline. However, he stresses that "no government has endorsed this act, and that private companies and individuals acting alone are responsible." In addition, Ould-Abdallah told the press that he approached several international NGOs, such as Global Witness, to trace the illicit fishing and waste-dumping. He added that he believes the toxic waste dumping is "a disaster off the Somali coast, a disaster (for) the Somali environment, the Somali population", and that what he terms "this illegal fishing, illegal dumping of waste" helps fuel the civil war in Somalia since the illegal foreign fishermen pay off corrupt local officials or warlords for protection or to secure counterfeit licenses. Ould-Abdallah noted that piracy will not prevent waste dumping:

I am convinced there is dumping of solid waste, chemicals and probably nuclear (waste).... There is no government (control) and there are few people with high moral ground[...] The intentions of these pirates are not concerned with protecting their environment. What is ultimately needed is a functioning, effective government that will get its act together and take control of its affairs.

—Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, the UN envoy for Somalia

Somali pirates which captured MV Faina, a Ukrainian ship carrying tanks and military hardware, accused European firms of dumping toxic waste off the Somali coast and declared that the $8m ransom for the return of the ship will go towards cleaning up the waste. The ransom demand is a means of "reacting to the toxic waste that has been continually dumped on the shores of our country for nearly 20 years", Januna Ali Jama, a spokesman for the pirates said. "The Somali coastline has been destroyed, and we believe this money is nothing compared to the devastation that we have seen on the seas."

These issues have generally not been reported in international media when reporting on piracy.

According to Muammar al-Gaddafi, "It is a response to greedy Western nations, who invade and exploit Somalia’s water resources illegally. It is not a piracy, it is self defence."

Pirate leader Sugule Ali said their motive was "to stop illegal fishing and dumping in our waters ... We don't consider ourselves sea bandits. We consider sea bandits [to be] those who illegally fish and dump in our seas and dump waste in our seas and carry weapons in our seas." Also, the independent Somali news-site WardherNews found that 70 percent "strongly supported the piracy as a form of national defence of the country's territorial waters".

Waste dumping

Following the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 2004, there have emerged allegations that after the outbreak of the Somali Civil War in late 1991, Somalia's long, remote shoreline was used as a dump site for the disposal of toxic waste. The huge waves which battered northern Somalia after the tsunami are believed to have stirred up tonnes of nuclear and toxic waste that was illegally dumped in Somali waters by several European firms — front companies created by the Italian mafia. The European Green Party followed up these revelations by presenting before the press and the European Parliament in Strasbourg copies of contracts signed by two European companies—the Italian Swiss firm, Achair Partners, and an Italian waste broker, Progresso—and representatives of the warlords then in power, to accept 10 million tonnes of toxic waste in exchange for $80 million (then about £60 million). According to a report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) assessment mission, there are far higher than normal cases of respiratory infections, mouth ulcers and bleeding, abdominal hemorrhages and unusual skin infections among many inhabitants of the areas around the northeastern towns of Hobbio and Benadir on the Indian Ocean coast—diseases consistent with radiation sickness. UNEP continues that the current situation along the Somali coastline poses a very serious environmental hazard not only in Somalia but also in the eastern Africa sub-region.

In 1992, reports ran in the European press of "unnamed European firms" contracting with local warlords to dump toxic waste both in Somalia and off Somalia's shores. The United Nations Environment Program was called in to investigate, and the Italian parliament issued a report later in the decade. Several European "firms" — really front companies created by the Italian mafia — contracted with local Somali warlords to ship hundreds of thousands of tons of toxic industrial waste from Europe to Somalia.

—Troy S. Thomas, Warlords rising: confronting violent non-state actors

Under Article 9(1)(d) of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, it is illegal for "any transboundary movement of hazardous wastes or other wastes: that results in deliberate disposal (e.g. dumping) of hazardous wastes or other wastes in contravention of this Convention and of general principles of international law".

According to Nick Nuttall of the United Nations Environmental Programme, "Somalia has been used as a dumping ground for hazardous waste starting in the early 1990s, and continuing through the civil war there", and "European companies found it to be very cheap to get rid of the waste, costing as little as $2.50 a tonne, where waste disposal costs in Europe are closer to $1000 per tonne."

Illegal fishing

At the same time, foreign trawlers began illegally fishing Somalia's seas, with an estimated $300 million of tuna, shrimp, and lobster being taken each year, depleting stocks previously available to local fishermen. Through interception with speedboats, Somali fishermen tried to either dissuade the dumpers and trawlers or levy a "tax" on them as compensation, as Segule Ali's previously mentioned quote notes. Peter Lehr, a Somalia piracy expert at the University of St. Andrews says "It's almost like a resource swap, Somalis collect up to $100 million a year from pirate ransoms off their coasts and the Europeans and Asians poach around $300 million a year in fish from Somali waters." The UK's Department for International Development (DFID) issued a report in 2005 stating that, between 2003 and 2004, Somalia lost about

$100 million in revenue due to illegal

tuna and shrimp fishing in the country's exclusive economic zone by foreign trawlers.

According to Roger Middleton of Chatham House, "The problem of overfishing and illegal fishing in Somali waters is a very serious one, and does affect the livelihoods of people inside Somalia [...] the dumping of toxic waste on Somalia's shores is a very serious issue, which will continue to affect people in Somalia long after the war has ended, and piracy is resolved." To lure fish to their traps, foreign

trawlers reportedly also use fishing equipment under prohibition such as nets with very small mesh sizes and sophisticated underwater lighting systems.

Under Article 56(1)(b)(iii) of the Law of the Sea Convention:

"In the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State has jurisdiction as provided for in the relevant provisions of this Convention with regard to the protection and preservation of the marine environment".

Article 57 of the Convention in turn outlines the limit of that jurisdiction:

"The exclusive economic zone shall not extend beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured".

Anti-piracy measures - Self-defense

The third volume of the handbook: Best Management Practices to Deter Piracy off the Coast of Somalia and in the Arabian Sea Area (known as BMP3) is the current authoritative guide for merchant ships on self-defense against pirates. The guide is issued and updated by a consortium of interested international shipping and trading organizations including the EU, NATO and the International Maritime

Bureau. It is distributed primarily by the Maritime Security Centre – Horn of Africa (MSCHOA) – the planning and coordination authority for EU naval forces (EUNAVFOR). BMP3 encourages vessels to register their voyages through the region with MSCHOA as this registration is a key component of the operation of the International Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC) (the navy patrolled route through the Gulf of Aden). BMP3 also contains a chapter entitled "Self-Protective Measures" which lays out a list of steps a merchant vessel can take on its own to make itself less of a target to pirates and make it better able to repel an attack if one occurs. This list includes doing thing like ringing the deck of the ship with razor wire, rigging fire-hoses to spray sea-water over the side of the ship (to hinder boardings), having a distinctive pirate alarm, hardening the bridge against gunfire and creating a "citadel" where the crew can retreat in the event pirates get on board. Other unofficial self-defense measures that can be found on merchant vessels include the setting up of mannequins posing as armed guards or firing flares at the pirates.

Though it varies by country, generally peacetime law in the 20th and 21st centuries has not allowed merchant vessels to carry weapons. As a response to the rise in modern piracy, however, the U.S. Government changed its rules so that it is now possible for US-flagged vessels to embark a team of armed private security guards. Other countries and organisations have similarly followed suit. This has given birth to a new breed of private security companies who provide training and protection for crew members and cargo and have proved effective in countering pirate attacks. The USCG leaves it to ship owners' discretion to determine if those guards will be armed. Seychelles has become a central location for international anti-piracy operations, hosting the Anti-Piracy Operation Center for the Indian Ocean. In 2008, VSOS became the first authorized armed maritime security company to operate in the Indian Ocean region.

With safety trials complete in the late 2000s, laser dazzlers have been developed for defensive purposes on super-yachts. They can be effective up to 2.5 miles with the effects going from mild disorientation to flash blindness at closer range.

In February 2012, Italian Marines based on the tanker Enrica Rexie allegedly fired on an Indian fishing trawler off Kerala, killing two of her eleven crew. The Marines allegedly mistook the fishing vessel as a pirate vessel. The incident sparked a diplomatic row between India and Italy. Enrica Rexie was ordered into Kochi where her crew were questioned by officers of the Indian Police.

Military presence

The military response to pirate attacks has brought about a rare show of unity by countries that are either openly hostile to each other, or at least wary of cooperation, military or otherwise.

Currently there are three international naval task forces in the region, with numerous national vessels and task forces entering and leaving the region, engaging in counter-piracy operations for various lengths of time. The three international task forces which comprise the bulk of counter-piracy operations are Combined Task Force 150 (whose overarching mission is Operation Enduring Freedom), Combined Task Force 151 (which was set up in 2009 specifically to run counter-piracy operations) and the EU naval task force operating under Operation Atalanta. All counter-piracy operations are coordinated through a monthly planning conference called Shared Awareness and Deconfliction (SHADE). Originally having representatives only from NATO, the EU, and the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) HQ in Bahrain, it now regularly attracts representatives from over 20 countries.

As part of the international effort, Europe plays a significant role in combating piracy off of the coast of the Horn of Africa. The European Union under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) launched EU NAVFOR Somalia – Operation Atalanta (in support of Resolutions 1814 (2008), 1816 (2008), 1838 (2008) and 1846 (2008) of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC)). This operation is working to protect humanitarian aid and reduce the disruption to the shipping routes and the de-stabilising of the maritime environment in the region. To date, 26 countries have brought some kind of contribution to the operation. 13 EU Member States have provided an operational contribution to EU NAVFOR, either with ships, with maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft, or with Vessel Protection Detachment (VPD) team. This includes France, Spain, Germany, Greece, Sweden, Netherlands, Italy, Belgium, United Kingdom (also hosting the EU NAVFOR Operational headquarters), Portugal, Luxembourg, Malta and Estonia. 9 other EU Member States have participated in the effort providing military staff to work at the EU NAVFOR Operational Headquarters (Northwood Headquarters – UK) or onboard units. These are Cyprus, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Ireland and Finland. Finally, 4 non-EU Member States, Norway (who has also provided an operational contribution with a warship regularly deploying), Croatia, Ukraine and Montenegro, have so far also brought their contribution to EU

NAVFOR.

At any one time, the European force size fluctuates according to the monsoon seasons, which determine the level of piracy. It typically consists of 5 to 10 Surface Combatants (Naval ships), 1 to 2 Auxiliary ships and 2 to 4 Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Aircraft. Including land-based personnel, Operation Atalanta consists of a total of around 2,000 military personnel. EU NAVFOR operates in a zone comprising the south of the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and the western part of the Indian Ocean including the Seychelles, which represents an area of 2,000,000 square nautical miles.

Additionally, there are, and have been, several naval deployments by non-multinational task forces in the past. Some notable ones include:

On 29 May 2009, Australia pledged its support, redirecting Australian Warship, HMAS Warramunga from duties in the Persian Gulf to assist in the fighting of Piracy.

On 26 December 2008, China dispatched two destroyers Haikou (171), Wuhan (169) and the supply ship Weishanhu (887) to the Gulf of Aden. A team of 16 Chinese Special Forces members from its Marine Corps armed with attack helicopters were on board. Subsequent to their initial deployment, China has maintained a three-ship flotilla of two warships and one supply ship in the Gulf of Aden by assigning ships to the area on a three-month basis.

The U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Navy both support the actions of the Combined Task Force 151 in their anti-piracy missions in the area.

To protect Indian ships and Indian citizens employed in seafaring duties, Indian Navy commenced anti-piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden from 23 Oct 08. A total of 21 IN ships have been deployed in the Gulf of Aden since Oct 08. In addition to escorting Indian flagged ships, ships of other countries have also been escorted. Merchant ships are currently being escorted along the entire length of the (490 nm long and 20 nm wide) Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC) that has been promulgated for use by all merchant vessels. A total of 1181 ships (144 Indian flagged and 1037 foreign flagged from different countries) have been escorted by IN ships in the Gulf of Aden since Oct 08. During its deployments for anti-piracy operations, the Indian Naval ships have prevented 15 piracy attempts on merchant vessels.

In response to the increased activity of the INS Tabar, India sought to augment its naval force in the Gulf of Aden by deploying the larger INS Mysore to patrol the area. Somalia also added India to its list of states, including the U.S. and France, who are permitted to enter its territorial waters, extending up to 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) from the coastline, in an effort to check piracy. An Indian naval official confirmed receipt of a letter acceding to India's prerogative to check such piracy. "We had put up a request before the Somali government to play a greater role in suppressing piracy in the Gulf of Aden in view of the United Nations resolution. The TFG government gave its nod recently." India also expressed consideration to deploy up to four more warships in the region. On 14 March 2011, the Indian navy reportedly had seized 61 pirates and rescued 13 crew from the vessel, which had been used as a mother ship from where pirates launched attacks around the Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, a Bangladeshi ship hijacked by pirates last year was freed after a ransom was paid.

Norway announced on 27 February 2009, that it would send the frigate HNoMS Fridtjof Nansen to the coast of Somalia to fight piracy. Royal Norwegian Navy Fridtjof Nansen joined EU NAVFOR's international naval force in August.

Russia also chose to send more warships to combat piracy near Somalia following the announcement from the International Maritime Bureau terming the menace as having gone "out of control."

Due to their proximity to Somalia, the coast guard of

Seychelles has become increasingly involved in

counter-piracy in the region. On 30 March 2010, a

Seychelles Coast Guard Trinkat class patrol vessel

rescued 27 hostages and sank two pirate vessels.

Other non-NATO and non-EU countries have, at one time or

another, contributed to counter-piracy operations.

Pakistan, South Korea, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, Saudi

Arabia and Iran have all sent ships to the region,

sometimes joining with the existing CTFs, sometimes

operating independently.

Royal Australian Air Force Lockheed P-3 Orion surveillance plane patrol the ocean between the southern

coast of Oman and the Horn of Africa. The anti-piracy flights are operated from

UAE. The Spanish Air Force also deployed P-3s to assist the international effort against piracy in Somalia. On 29 October 2008, a Spanish P-3 aircraft patrolling the coast of Somalia reacted to a distress call from an oil tanker in the Gulf of Aden. In order to deter the pirates, the aircraft flew over the pirates three times as they attempted to board the tanker, dropping a smoke bomb on each pass. After the third pass, the attacking pirate boatsbroke off their attack. Later, on 29 March 2009, the same P-3 pursued the assailants of the German navy tanker Spessart (A1442), resulting in the capture of the pirates. In April 2011, the Portuguese Air Force also contributed to Operation Ocean Shield by sending a P-3C which had early success when on its

A maritime conference was also held in Mombasa to discuss

the rising concern of regional piracy with a view to give

regional and world governments recommendations to deal

with the menace. The International Transport Workers

Federation (ITWF) organised the regional African maritime

unions’ conference, the first of its kind in Africa.

Godfrey Matata Onyango, executive secretary of the

Northern Corridor Transit Coordination Authority said

that "We cannot ignore to discuss the piracy menace

because it poses a huge challenge to the maritime

industry and if not controlled, it threats to chop off

the regional internal trade. The cost of shipping will

definitely rise as a result of the increased war

insurance premium due to the high risk off the Gulf of

Aden." In 2008 Pakistan offered the services of the

Pakistan Navy to the United Nations in order to help

combat the piracy in Somalia "provided a clear mandate

was given."

Current fleet of vessels in operation

The article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to

out-of-date information. Please help improve the article

by updating it. There may be additional information on

the talk page. (October 2010)

Vessels, aircraft and personnel whose primary mission is

to conduct anti-piracy activities come from different

countries and are assigned to the following missions:

Operation Ocean Shield (NATO and partner states),

Atalanta (EU and partner states), Combined Task Force

151, independent missions of Japan, India, Russia, PR

China, South Korea, Iran, Malaysia. Additionally

resources dedicated for the War on Terror missions of

Combined Task Force 150 and Enduring Freedom – Horn of

Africa also operate against the pirates.

|

Country

|

Mission

|

Sailors

|

Ships

|

Cost

[Mil of USD per annum]

|

Start

|

End

|

|

Royal

Australian Navy

Royal

Australian Navy

|

CTF

150

|

~250

|

1

frigate (as part of Operation Slipper duties)

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

Belgian

Navy

Belgian

Navy

|

Atalanta

|

170

|

1

Frigate Louise-Marie

|

?

|

Sep

1, 2009

Oct 20, 2010

|

Dec

16, 2009

Jan 20, 2011

|

|

Bulgarian

Navy

Bulgarian

Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

130

|

Wielingen

class frigate 41 Drazki

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

Royal

Canadian Navy

Royal

Canadian Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

240

|

HMCS Fredericton

|

?

|

November

2009

|

May

4, 2010

|

|

Chinese

People's Liberation Army Navy

Chinese

People's Liberation Army Navy

|

|

~800

including PLA marines

|

13th

Flotilla/TF 568: Hengyang (ex-Chaohu Type 054A/FFG-568), Huangshang

(Type 054A/FFG-570), Qinghaihu (Nancang Class/885)

|

?

|

13th

Flotilla/TF 568: November 21, 2012

|

?

|

|

French

Navy

French

Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield or Atalanta

|

?

|

Germinal,

Floréal,

La

Fayette, avisos,

Améthyste

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

German

Navy

German

Navy

|

Atalanta

|

ca.

300

|

1

(Frigate Lübeck

(F214))

|

60

(45 Mio. EUR)

|

December

8, 2008

|

December

1, 2012

|

|

Greek

Navy

Greek

Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

176-196

|

4

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

Indian

Navy

Indian

Navy

|

|

540

|

Frigate

INS

Tabar (F44)

Destroyer INS

Mysore (D60)

Frigate INS Godavari

INS Cankarso

INS Kalpeni

|

1

|

23

Oct 2008

|

?

|

|

Islamic

Republic Iran Navy

Islamic

Republic Iran Navy

|

|

?

|

Bandar

Abbas; Naghdi; Jamaran

|

1

|

?

|

?

|

|

Italian

Navy

Italian

Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

240

|

1

(D560 Durand de la Penne)

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

Japan

Maritime Self-Defense Force Japan

Maritime Self-Defense Force

|

|

400

|

1st

Escort Division:DD-113

Sazanami, DD-106

Samidare

2nd Escort Division:DD-102

Harusame, DD-154

Amagiri,

3rd Escort Division:DD-110

Takanami, DD-155

Hamagiri

4th Escort Division:DD-111

Onami, DD-157

Sawagiri

5th Escort Division:DD-101

Murasame, DD-153

Yugiri

6th Escort Division:DD-112

Makinami, DD-156

Setogiri

7th Escort Division:DD-104

Kirisame, DD-103

Yudachi

8th Escort Division:DD-105

Inazuma, DD-113 Sazanami

9th Escort Division:DD-106 Samidare, DD-158

Umigiri

10th Escort Division:DD-110 Takanami, DD-111 Onami

11th Escort Division:DD-101 Murasame, DD-102 Harusame

12th Escort Division:DD-107

Ikazuchi, DD-157 Sawagiri

|

?

|

March

14, 2009

July 6, 2009

October 13, 2009

January 29, 2010

May 10, 2010

August 23, 2010

December 1, 2010

March 15, 2011

June 20, 2011

October 11, 2011

January 21, 2012

May 11, 2012

|

August

16, 2009

November 29, 2009

March 18, 2010

July 2, 2010

October 15, 2010

January 18, 2011

May 9, 2011

August 11, 2011

December 3, 2011

March 12, 2012

July 5, 2012

|

|

Republic

of Korea Navy

Republic

of Korea Navy

|

CTF

150

|

300

|

1

Destroyer (Currently Choi

Young DDH-981)

|

1

|

April

16, 2009

|

?

|

|

Royal

Malaysian Navy

Royal

Malaysian Navy

|

|

unknown

|

Support

Ship Bunga Mas 5

|

3

|

?

|

?

|

|

Royal

Netherlands Navy

Royal

Netherlands Navy

|

Atalanta

|

174-202

|

HNLMS

De Zeven Provinciën

|

1

|

March

26, 2009

|

August

2010

|

|

Pakistan

Navy

Pakistan

Navy

|

CTF

150

|

177

|

PNS

Badr

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

Portuguese

Navy

Portuguese

Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

180

|

1

(Frigate NRP Corte Real – NATO flotilla flagship)

|

?

|

June

2009

|

January

2010

|

|

Royal

Saudi Navy

Royal

Saudi Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

Russian

Navy

Russian

Navy

|

|

~350

|

3

(Destroyer Admiral

Panteleyev (BPK 548), Salvage Tugboat, Tanker

|

?

|

April

2009

|

?

|

|

Republic

of Singapore Navy

Republic

of Singapore Navy

|

CTF

151

|

240

|

LST

RSS

Persistence (209)

|

?

|

24

April 2009

|

?

|

|

Spanish

Navy

Spanish

Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

423

|

2

Frigates (F86

Canarias and F104 Méndez Núñez)

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

Turkish

Navy

Turkish

Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

503

|

2

(Frigates TCG

Giresun (F 491), TCG

Gokova (F 496))

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

Royal Navy

Royal Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield

|

950

|

HMS

Cumberland

HMS

Montrose

HMS

Northumberland

HMS

Monmouth

|

?

|

?

|

?

|

|

United States

Navy

United States

Navy

|

Operation

Ocean Shield, CTF 150, CTF

151

|

?

|

US

5th Fleet

|

?

|

?

|

Brian Murphy (Associated Press) reported on 8 January 2009 that Rear Admiral Terence E. McKnight, U.S. Navy, is to command a new multi-national naval force to confront piracy off the coast of Somalia. This new anti-piracy force was designated Combined Task Force 151 (CTF-151), a multinational task force of the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF). The USS San Antonio was designated as the flagship of Combined Task Force 151, serving as an afloat forward staging base (AFSB) for the following force elements:

14-member U.S. Navy visit, board, search, and seizure (VBSS) team.

8-member U.S. Coast Guard Law Enforcement Detachment (LEDET) 405.

Scout Sniper Platoon, 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit (26 MEU) cross-decked from the USS Iwo Jima (LHD-7).

3rd Platoon of the 2nd Battalion, 6th Marine's 'Golf' Infantry Company, a military police detachment, and intelligence personnel.

Fleet Surgical Team 8 with level-two surgical capability to deal with trauma, surgical, critical care and medical evacuation needs.

Approximately 75 Marines with six AH-1W Super Cobra and two UH-1N Huey helicopters from the Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 264 (HMM-264) of the 26th MEU cross-decked from the USS Iwo

Jima.

Three HH-60H helicopters from Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron 3 (HS-3) cross-decked from the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71).

Initially, CTF-151 consisted of the San Antonio, USS Mahan (DDG-72), and HMS Portland (F79), with additional warships expected to join this force.

On 28 January 2009, Japan announced its intention of sending a naval task force to join international efforts to stop piracy off the coast of Somalia. The deployment would be highly unusual, as Japan's non-aggressive constitution means Japanese military forces can only be used for defensive purposes. The issue has been controversial in Japan, although the ruling party maintains this should be seen as fighting crime on the high seas, rather than a "military" operation. The process of the Prime Minister of Japan, Taro Aso, giving his approval is expected to take approximately one month. However, the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) and the Japanese government face legal problems on how to handle attacks by pirates against ships that either have Japanese personnel, cargo or are under foreign control instead of being under Japanese control as current Article 9 regulations would hamper their actions when deployed to Somalia. It was reported on 4 February 2009, that the JMSDF was sending a fact-finding mission led by Gen Nakatani to the region prior to the deployment of the Murasame-class destroyer JDS DD-106 Samidare and the Takanami-class destroyer JDS DD-113 Sazanami to the coast of Somalia with a 13-man team composed of Japanese Ministry of Defense personnel, with members coming from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the JMSDF to visit Yemen, Djibouti, Oman, and Bahrain from February 8 to 20. Both JMSDF vessels are units of the 8th Escort Division of the 4th Escort Flotilla based in Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture. The JMSDF's special forces unit, the Special Boarding Unit is also scheduled to potentially deploy to Somalia. The SBU has been deployed alongside the two destroyers to Somalia on 14 March 2009.

According to JMSDF officials, the deployment would "regain the trust of the shipping industry, which was lost during the war." The JMSDF task force would be deployed off the coast of Somalia for 4 months. In its first mission, the Takanami-class destroyer JDS DD-113 Sazanami was able to ward off pirates attempting to hijack a Singaporean cargo ship. In addition, JMSDF P-3Cs are to be deployed in June from Djibouti to conduct surveillance on the Somali coast. The House of Representatives of Japan has passed an anti-piracy bill, calling for the JMSDF to protect non-Japanese ships and nationals, though there are some concerns that the pro-opposition House of Councillors may reject it. The Diet of Japan has passed an anti-piracy law that called for JMSDF forces to protect all foreign ships traveling off the coast of Somalia aside from protecting Japanese-owned/manned ships despite a veto from the House of Councillors, which the House of Representatives have overturned. In 2009, the destroyers Harusame and DD-154 Amagiri left port from Yokusuka to replace the two destroyers that had been dispatched earlier on March 2009. Under current arrangements, Japan Coast Guard officers would be responsible for arresting pirates since SDF forces are not allowed to have powers of arrest.

The South Korean navy is also making plans to participate in anti-piracy operations after sending officers to visit the US Navy's 5th Fleet in Bahrain and in Djibouti. The South Korean cabinet had approved a government plan to send in South Korean navy ships and soldiers to the coast of Somalia to participate in anti-pirate operations. The ROKN was sending the Chungmugong Yi Sun-sin class destroyer DDH 976 Munmu the Great to the coast of Somalia. The Cheonghae Unit task force was also deployed in Somalia under CTF 151.

The Swiss government calls for the deployment of Army Reconnaissance Detachment operators to combat Somali piracy with no agreement in Parliament as the proposal was rejected after it was voted. Javier Solana had said that Swiss soldiers could serve under the EU's umbrella.

The Philippine government ordered the dispatch of a Naval Gunfire Liaison Officers to work with the US Navy's 5th Fleet as part of its contribution against piracy.

On 12 June 2009, Bulgaria also announced plans to join the anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and protect Bulgarian shipping, by sending a frigate with a crew of 130 sailors.

The Danish Institute for Military Studies has in a

report proposed to establish a regionally based maritime unit: a Greater Horn of Africa Sea Patrol, to carry out surveillance in the area to secure free navigation and take on tasks such as fishery inspection and environmental monitoring. A Greater Horn of Africa Sea Patrol would comprise elements from the coastal states – from Egypt in the north to Tanzania in the south. The unit would be established with the support of the states that already have a naval presence in the area.

In February 2010, Danish special forces from the Absalon freed 25 people from the Antigua and Barbuda-flagged vessel Ariella after it was hijacked by pirates off the Somali coast. The crew members had locked themselves into a store-room.

Southern African waters are becomingly an increasingly attractive alternative to the more protected Eastern African sea lanes. The recent rise in counter-piracy patrols is pushing more pirates down the coast line into unprotected areas of the Indian Ocean, which will require the joint navies’ current patrols to widen their search area.

In January 2012, US military forces freed an American and a Danish hostage after a gun battle with pirates during a night-time helicopter raid in Somalia. Two US helicopters attacked the site where the hostages were being held, 12 miles north of the town of Adado. Nine pirates were killed. There were no US casualties.

In May 2012, EU Navfor conducted their first raid on pirate bases on the Somali mainland, destroying 5 pirate boats. The EU forces were transported by helicopter to the bases near the port of Harardhere, a well known pirate lair. The operation was carried out with the full support of the Somali government.

Somalia - Puntland

Between 2009 and 2010, the government of the autonomous Puntland region in northeastern Somalia enacted a number of reforms and pre-emptive measures as a part of its officially declared anti-piracy campaign. The latter included the arrest, trial and conviction of pirate gangs, as well as raids on suspected pirate hideouts and confiscation of weapons and equipment; ensuring the adequate coverage of the regional authority's anti-piracy efforts by both local and international media; sponsoring a social campaign led by Islamic scholars and community activists aimed at discrediting piracy and highlighting its negative effects; and partnering with the NATO alliance to combat pirates at sea. In May 2010, construction also began on a new naval base in the town of Bandar Siyada, located 25 km west of Bosaso, the commercial capital of Puntland. The facility is funded by Puntland's regional government in conjunction with Saracen International, a UK-based security company, and is intended to assist in more effectively combating piracy. The base will include a center for training recruits, and a command post for the naval force.

These numerous security measures appear to have borne fruit, as many pirates were apprehended in 2010, including a prominent leader. Puntland's security forces also reportedly managed to force out the pirate gangs from their traditional safe havens such as Eyl and

Gar'ad, with the pirates now primarily operating from Hobyo, El Danaan and Harardhere in the neighboring Galmudug region.

Following a Transitional Federal Government-Puntland cooperative agreement in August 2011 calling for the creation of a Somali Marine Force, of which the already established Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF) would form a part, the Puntland administration resumed training of PMPF naval officials. The Puntland Maritime Police Force is a locally recruited, professional maritime security force that is primarily aimed at fighting piracy off of the coast of Somalia, safeguarding the nation's marine resources, and providing logistics support to humanitarian efforts. Supported by the United Arab Emirates, PMPF officials are also trained by the Japanese Coast Guard.

Galmudug

Government officials from the Galmudug administration in the north-central Hobyo district have also reportedly attempted to use pirate gangs as a bulwark against Islamist insurgents from southern Somalia's conflict zones; other pirates are alleged to have reached agreements of their own with the Islamist groups, although a senior commander from the Hizbul Islam militia vowed to eradicate piracy by imposing sharia law when his group briefly took control of Harardhere in May 2010 and drove out the local pirates.

By the first half of 2010, these increased policing efforts by Somali government authorities on land along with international naval vessels at sea reportedly contributed to a drop in pirate attacks in the Gulf of Aden from 86 a year prior to 33, forcing pirates to shift attention to other areas such as the Somali Basin and the wider Indian Ocean.

Somaliland

The government of Somaliland, a self-declared republic that is internationally recognized as an autonomous region of Somalia, has adopted stringent anti-piracy measures, arresting and imprisoning pirates forced to make port in Berbera. According to officials in Hargeisa, Somaliland's capital, the Somaliland Coast Guard acts as an effective deterrent to piracy in waters under its jurisdiction.

Arab League summit

Following the seizure by Somali pirates of an Egyptian ship and a Saudi oil supertanker worth $100 million of oil, the Arab League, after a meeting in Cairo, has called for an urgent summit for countries overlooking the Red Sea, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Somalia, Jordan, Djibouti and Yemen. The summit would offer several solutions for the piracy problem, in addition to suggesting different routes and looking for a more secure passageway for ships.

Another possible means of intervention by the Red Sea Arab nations' navy might be to assist the current NATO anti-piracy effort as well as other navies.

United Nations

In June 2008, following a letter from the Somalian Transitional Federal Government (TFG) to the President of the UN Security Council requesting assistance for the TFG's efforts to tackle acts of piracy off the coast of Somalia, the UN Security Council unanimously passed a declaration authorizing nations that have the consent of the Transitional Federal Government to enter Somali territorial waters to deal with

pirates. The measure, which was sponsored by France, the United States and Panama, lasted six months. France initially wanted the resolution to include other regions with pirate problems, such as West Africa, but were opposed by Vietnam, Libya and most importantly by veto-holding China, who wanted the sovereignty infringement limited to Somalia.

The UN Security Council adopted a resolution on 20 November 2008, that was proposed by Britain to introduce tougher sanctions against Somalia over the country's failure to prevent a surge in sea piracy. The US circulated the draft resolution that called upon countries having naval capacities to deploy vessels and aircraft to actively fight against piracy in the region. The resolution also welcomed the initiatives of the European Union, NATO and other countries to counter piracy off the coast of Somalia. US Alternate Representative for Security Council Affairs Rosemary DiCarlo said that the draft resolution "calls on the secretary-general to look at a long-term solution to escorting the safe passage of World Food Programme ships." Even Somalia's Islamist militants stormed the Somali port of Harardheere in the hunt for pirates behind the seizure of a Saudi supertanker, the MV Sirius Star. A clan elder affiliated with the Islamists said "The Islamists arrived searching for the pirates and the whereabouts of the Saudi ship. I saw four cars full of Islamists driving in the town from corner to corner. The Islamists say they will attack the pirates for hijacking a Muslim ship."