|

TREASURE ISLAND - Robert Louis Stevenson 1850-1894

|

||

|

Treasure Island is an adventure novel by

Scottish author Robert Louis

Stevenson, narrating a tale of "buccaneers and buried gold". First published as a book on May 23, 1883, it was originally serialized in the children's magazine Young Folks between 1881–82 under the title Treasure Island; or, the mutiny of the Hispaniola with Stevenson adopting the pseudonym Captain George North.

Jim Hawkins sitting in the apple-barrel, listening to the pirates

The novel is divided into 6 parts and 34 chapters: Jim Hawkins is the narrator of all except for chapters 16-18 which are narrated by Doctor Livesey.

Of the two pirates left aboard, only one is still alive: the coxswain, Israel Hands, who has murdered his comrade in a drunken brawl and been badly wounded in the process. Hands agrees to help Jim helm the ship to a safe beach in exchange for medical treatment and brandy, but once the ship is approaching the beach Hands tries to murder Jim. Jim escapes by climbing the rigging, and when Hands tries to skewer him with a thrown dagger, Jim reflexively shoots Hands dead. Having beached the Hispaniola securely, Jim returns to the stockade under cover of night and sneaks back inside. Because of the darkness, he does not realize until too late that the stockade is now occupied by the pirates, and he is captured. Silver, whose always-shaky command has become more tenuous than ever, seizes on Jim as a hostage, refusing his men's demands to kill him or torture him for information.

Silver's rivals in the pirate crew, led by George Merry, give Silver the Black Spot and move to depose him as captain. Silver answers his opponents eloquently, rebuking them for defacing a page from the Bible to create the Black Spot and revealing that he has obtained the treasure map from Dr. Livesey, thus restoring the crew's confidence. The following day, the pirates search for the treasure. They are shadowed by Ben Gunn, who makes ghostly sounds to dissuade them from continuing, but Silver forges ahead and locates where Flint's treasure is buried. The pirates discover that the cache has been rifled and the

treasure is gone.

One More Step, Mr. Hands by N. C. Wyeth, 1911, for Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

The enraged

pirates turn on Silver and Jim, but Ben Gunn, Dr. Livesey and Abraham Gray attack the pirates, killing two and dispersing the rest. Silver surrenders to Dr. Livesey, promising to return to his duty. They go to Ben Gunn's cave where Gunn has had the treasure hidden for some months. The treasure is divided amongst Trelawney and his loyal men, including Jim and Ben Gunn, and they return to England, leaving the surviving pirates marooned on the island. Silver escapes with the help of the fearful Ben Gunn and a small part of the treasure 3/400 guineas. Remembering Silver, Jim reflects that "I dare say he met his old Negress (wife), and perhaps still lives in comfort with her and Captain Flint (his parrot). It is to be hoped so, I suppose, for his chances of comfort in another world are very small." Backstory

Treasure Island contains numerous references to fictional past events, gradually revealed throughout, that shed light upon the events of the main

plot. Minor characters

Alan: A sailor who does not mutiny. He is killed by the mutineers for his loyalty and his dying scream is heard by several.

Treasure Island 1911 book cover

Historical allusions - Real pirates and piracies

Five real-life pirates mentioned are William Kidd (active 1696-1699), Blackbeard (1716–1718), Edward England (1717–1720), Howell Davis (1718–1719), and Bartholomew Roberts (1718–1722). Kidd actually buried treasure on Gardiners Island, though the booty was recovered by authorities soon afterwards.

Allegedly Hands was taken ashore to be treated for his injury and was not at Blackbeard's last fight (the incident is depicted in Tim Powers' novel On Stranger Tides); this alone saved him from the gallows; supposedly he later became a beggar in England.

1689: A pirate whistles "Lillibullero" (1689).

Time frame

Stevenson deliberately leaves the exact date of the novel obscure, Hawkins writing that he takes up his pen "in the year of grace 17--." However, some of the action can be connected with dates, although it is unclear if Stevenson had an exact chronology in mind. The first date is 1745, as established both by Dr. Livesey's service at Fontenoy and a date appearing in Billy Bones's log. Admiral Hawke is a household name, implying a date later than 1747, when Hawke gained fame at the Battle of Cape Finisterre and was promoted to Admiral, but prior to Hawke's death in 1781.

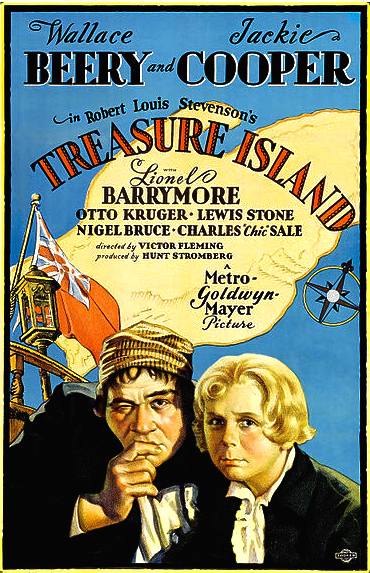

Treasure Island film poster, Charlton Heston and Christian Bale

Characters

Squire Trelawney may have been named for Edward Trelawney, Governor of Jamaica 1738-1752.

Admiral Benbow

The Llandoger Trow in Bristol is claimed to be the inspiration for the Admiral Benbow, though the inn in the book is not in Bristol.

Spyglass Tavern

The Hole in the Wall, Bristol is claimed to be the Spyglass

Tavern. Flint's death house

The Pirate's House in Savannah, Georgia is where Captain Flint is claimed to have spent his last

days, and his ghost is claimed to haunt the property

CHAPTER 1 - THE OLD BUCCANEER - The Old Sea-dog at the Admiral Benbow

I remember him as if it were yesterday, as he came plodding to the inn door, his sea-chest following behind him in a hand- barrow -- a tall, strong, heavy, nut-brown man, his tarry pigtail falling over the shoulder of his soiled blue coat, his hands ragged and scarred, with black, broken nails, and the sabre cut across one cheek, a dirty, livid white. I remember him looking round the cover and whistling to himself as he did so, and then breaking out in that old sea-song that he sang so often afterwards: "Fifteen men on the dead man's chest -- Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!" In the high, old tottering voice that seemed to have been tuned and broken at the capstan bars. Then he rapped on the door with a bit of stick like a handspike that he carried, and when my father appeared, called roughly for a glass of rum. This, when it was brought to him, he drank slowly, like a connoisseur, lingering on the taste and still looking about him at the cliffs and up at our signboard.

"This is a handy cove," says he at length; "and a pleasant sittyated grog-shop. Much company, mate?" My father told him no, very little company, the more was the pity. "Well, then," said he, "this is the berth for me. Here you, matey," he cried to the man who trundled the barrow; "bring up alongside and help up my chest. I'll stay here a bit," he continued. "I'm a plain man; rum and bacon and eggs is what I want, and that head up there for to watch ships off. What you mought call me? You mought call me captain. Oh, I see what you're at -- there"; and he threw down three or four gold pieces on the threshold. "You can tell me when I've worked through that," says he, looking as fierce as a commander.

Treasure Island book cover illustration by Louis Rhead and Frank Schoonover

And indeed bad as his clothes were and coarsely as he spoke, he had none of the appearance of a man who sailed before the mast, but seemed like a mate or skipper accustomed to be obeyed or to strike. The man who came with the barrow told us the mail had set him down the morning before at the Royal George, that he had inquired what inns there were along the coast, and hearing ours well spoken of, I suppose, and described as lonely, had chosen it from the others for his place of residence. And that was all we could learn of our guest.

He was a very silent man by custom. All day he hung round the cove or upon the cliffs with a brass telescope; all evening he sat in a corner of the parlour next the fire and drank rum and water very strong. Mostly he would not speak when spoken to, only look up sudden and fierce and blow through his nose like a fog-horn; and we and the people who came about our house soon learned to let him be. Every day when he came back from his stroll he would ask if any seafaring men had gone by along the road. At first we thought it was the want of company of his own kind that made him ask this question, but at last we began to see he was desirous to avoid them. When a seaman did put up at the Admiral Benbow (as now and then some did, making by the coast road for Bristol) he would look in at him through the curtained door before he entered the parlour; and he was always sure to be as silent as a mouse when any such was present. For me, at least, there was no secret about the matter, for I was, in a way, a sharer in his alarms. He had taken me aside one day and promised me a silver fourpenny on the first of every month if I would only keep my "weather-eye open for a seafaring man with one leg" and let him know the moment he appeared. Often enough when the first of the month came round and I applied to him for my wage, he would only blow through his nose at me and stare me down, but before the week was out he was sure to think better of it, bring me my four-penny piece, and repeat his orders to look out for "the seafaring man with one leg." How that personage haunted my dreams, I need scarcely tell you. On stormy nights, when the wind shook the four corners of the house and the surf roared along the cove and up the cliffs, I would see him in a thousand forms, and with a thousand diabolical expressions. Now the leg would be cut off at the knee, now at the hip; now he was a monstrous kind of a creature who had never had but the one leg, and that in the middle of his body. To see him leap and run and pursue me over hedge and ditch was the worst of nightmares. And altogether I paid pretty dear for my monthly fourpenny piece, in the shape of these abominable fancies. But though I was so terrified by the idea of the seafaring man with one leg, I was far less afraid of the captain himself than anybody else who knew him. There were nights when he took a deal more rum and water than his head would carry; and then he would sometimes sit and sing his wicked, old, wild sea-songs, minding nobody; but sometimes he would call for glasses round and force all the trembling company to listen to his stories or bear a chorus to his singing. Often I have heard the house shaking with "Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum," all the neighbours joining in for dear life, with the fear of death upon them, and each singing louder than the other to avoid remark. For in these fits he was the most overriding companion ever known; he would slap his hand on the table for silence all round; he would fly up in a passion of anger at a question, or sometimes because none was put, and so he judged the company was not following his story. Nor would he allow anyone to leave the inn till he had drunk himself sleepy and reeled off to bed.

His stories were what frightened people worst of all. Dreadful stories they were -- about hanging, and walking the plank, and storms at sea, and the Dry Tortugas, and wild deeds and places on the Spanish Main. By his own account he must have lived his life among some of the wickedest men that God ever allowed upon the sea, and the language in which he told these stories shocked our plain country people almost as much as the crimes that he described. My father was always saying the inn would be ruined, for people would soon cease coming there to be tyrannized over and put down, and sent shivering to their beds; but I really believe his presence did us good. People were frightened at the time, but on looking back they rather liked it; it was a fine excitement in a quiet country life, and there was even a party of the younger men who pretended to admire him, calling him a "true sea-dog" and a "real old salt" and such like names, and saying there was the sort of man that made England terrible at sea.

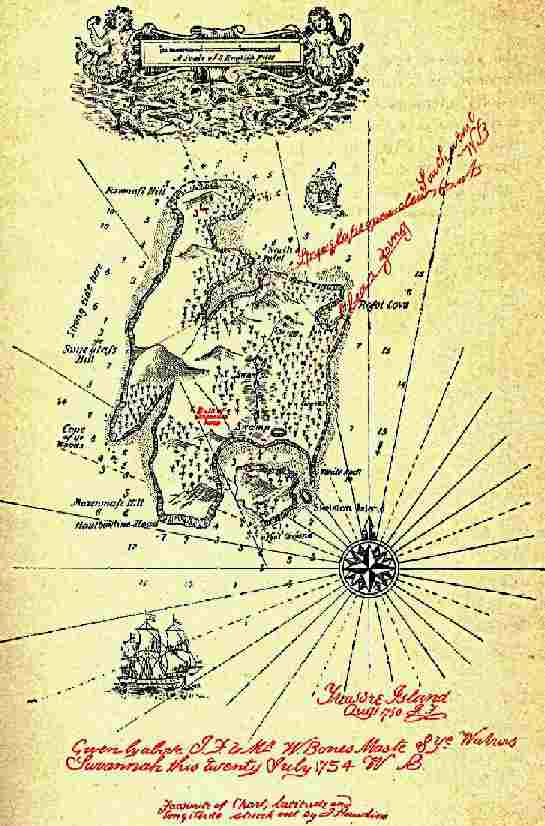

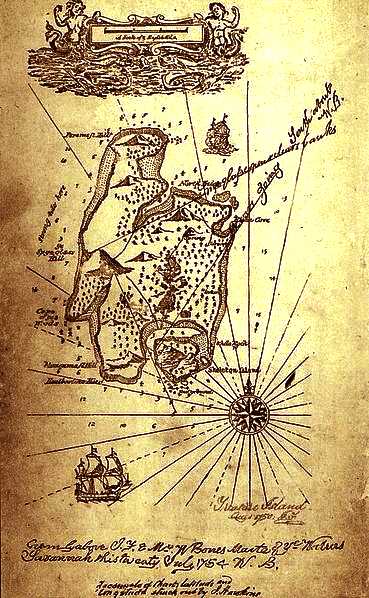

Treasure Island map of Hispaniola?

Pirate or Pyrates?

Today, the words "Pirate" or "Piracy" are spelled with an "I". In the Golden Age of Piracy, spelling was a haphazard kind of thing, and the word were often spelled with a "y". So there was a time when the word Pirate was spelled Pyrate, Pirate, Pyrat, or Pirat. I use pyrates, just for the whimsy and feel of it.

TREASURE

Treasure

(from Greek θησαυρός - thēsauros,

meaning "treasure store", romanized as thesaurus) is a

concentration of riches, often one which is considered lost or forgotten

until being rediscovered. Some jurisdictions legally define what

constitutes treasure, such as in the British Treasure Act 1996.

Treasure Island - illustrated book cover

Searching

for hidden treasure is a common theme in legend and fiction; real-life

treasure hunters also exist, and can seek lost wealth for a living.

Buried treasure

A

buried treasure is an important part of the popular beliefs surrounding

pirates. According to popular conception, pirates often buried their

stolen fortunes in remote places, intending to return for them later

(often with the use of treasure maps).

Map created by Robert Lewis Stevenson for Treasure Island

Treasure maps

A

treasure map is a variation of a map to mark the location of buried

treasure, a lost mine, a valuable secret or a hidden location. More

common in fiction than in reality, "pirate treasure maps" are

often depicted in works of fiction as hand drawn and containing arcane

clues for the characters to follow. Regardless of the term's literary

use, anything that meets the criterion of a "map" that

describes the location of a "treasure" could appropriately be

called a "treasure map." Copper scroll

One

of the earliest known instances of a document listing buried treasure is

the copper scroll, which was recovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls near

Qumran in 1952. Believed to have been written between 50 and 100 AD, the

scroll contains a list of 63 locations with detailed directions pointing

to hidden treasures of gold and silver. The following is an English

translation of the opening lines of the Copper Scroll:

Treasure Island book illustration - jolly boat & Hispaniola schooner

Pirates

Although

buried pirate treasure is a favorite literary theme, there are very few

documented cases of pirates actually burying treasure, and no documented

cases of a historical pirate treasure map. One documented case of buried

treasure involved Francis Drake who buried Spanish gold and silver after

raiding the train at Nombre de Dios -- after Drake went to find his

ships, he returned six hours later and retrieved the loot and sailed for

England. Drake did not create a map. Another case in 1720 involved

British Captain Stratton of the Prince Eugene who, after supposedly

trading rum with pirates in the Caribbean, buried his gold

near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. One of his crew, Morgan Miles,

turned him in to the authorities, and it is assumed the loot was

recovered. In any case, Captain Stratton was not a pirate, and made no

map.

Treasure

Island

Treasure maps in fiction

Treasure

maps have taken on numerous permutations in literature and film, such as

the stereotypical tattered chart with an over-sized "X" (as in

"X marks the spot") to denote the treasure's location, first

made popular by Robert Louis Stevenson in Treasure Island (1883), a

cryptic puzzle (in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug" (1843)),

or a tattoo as seen in the video game The Space Adventure - Cobra: The

Legendary Bandit (1991) and the film Waterworld (1995). Treasure maps in literature

The treasure map may serve several purposes as a plot device in works of fiction. Typically, it can be the motivation, causing the characters to begin a quest. It can be used to steer the plot (exposition), explaining in a concise way where the characters must go on their quest, or a map can be used to illustrate, at various points in the story, how far the quest has progressed.

Treasure maps in film

In

the 1985 film The Goonies, an old treasure map leads to the secret stash

of a legendary 17th century pirate, an almost exact imitation of

Stevenson's plot in Treasure Island. In the 2004 film National Treasure,

a treasure map becomes the source of the quest itself. In the 1994

comedy City Slickers 2: The Legend of Curly's Gold, a treasure map is

made by criminals who are analogous to modern day pirates. In the film

Waterworld, an extremely vague and cryptic treasure map has been

tattooed on the back of the child character Enola. This map leads the

characters to dry-land, which in the context of the film, is a treasure.

Legends

The

list here is not exhaustive, there are for example many lost mines; King

Solomon's is a good one. Treasure troves

Treasure Island 1990 film trailer

CHAPTER 2 - BLACK DOG DISAPPEARS

It was not very long after this that there occurred the first of the mysterious events that rid us at last of the captain, though not, as you will see, of his affairs. It was a bitter cold winter, with long, hard frosts and heavy gales; and it was plain from the first that my poor father was little likely to see the spring. He sank daily, and my mother and I had all the inn upon our hands; and were kept busy enough, without paying much regard to our unpleasant guest.

It was one January morning, very early—a pinching, frosty morning—the cove all grey with hoar-frost, the ripple lapping softly on the stones, the sun still low and only touching the hilltops and shining far to seaward. The captain had risen earlier than usual, and set out down the beach, his cutlass swinging under the broad skirts of the old blue coat, his brass telescope under his arm, his hat tilted back upon his head. I remember his breath hanging like smoke in his wake as he strode off, and the last sound I heard of him, as he turned the big rock, was a loud snort of indignation, as though his mind was still running upon Dr. Livesey.

Well, mother was up-stairs with father; and I was laying the breakfast-table against the captain's return, when the parlour door opened, and a man stepped in on whom I had never set my eyes before. He was a pale, tallowy creature, wanting two fingers of the left hand; and, though he wore a cutlass, he did not look much like a fighter. I had always my eye open for seafaring men, with one leg or two, and I remember this one puzzled me. He was not sailorly, and yet he had a smack of the sea about him too.

I asked him what was for his service, and he said he would take rum; but as I was going out of the room to fetch it he sat down upon a table, and motioned me to draw near. I paused where I was with my napkin in my hand.

"Come here, sonny," says he. "Come nearer here."

I took a step nearer.

"Is this here table for my mate, Bill?" he asked, with a kind of leer. I told him I did not know his mate Bill; and this was for a person who stayed in our house, whom we called the captain.

"Well," said he, "my mate Bill would be called the captain, as like as not. He has a cut on one cheek, and a mighty pleasant way with him, particularly in drink, has my mate, Bill. We'll put it, for argument like, that your captain has a cut on one cheek—and we'll put it, if you like, that that cheek's the right one. Ah, well! I told you. Now, is my mate Bill in this here house?" I told him he was out walking.

"Which way, sonny? Which way is he gone?"

And when I had pointed out the rock and told him how the captain was likely to return, and how soon, and answered a few other questions, "Ah," said he, "this'll be as good as drink to my mate Bill." The expression of his face as he said these words was not at all pleasant, and I had my own reasons for thinking that the stranger was mistaken, even supposing he meant what he said. But it was no affair of mine, I thought; and, besides, it was difficult to know what to do. The stranger kept hanging about just inside the inn door, peering round the corner like a cat waiting for a mouse. Once I stepped out myself into the road, but he immediately called me back, and, as I did not obey quick enough for his fancy, a most horrible change came over his tallowy face, and he ordered me in, with an oath that made me jump. As soon as I was back again he returned to his former manner, half fawning, half sneering, patted me on the shoulder, told me I was a good boy, and he had taken quite a fancy to me. "I have a son of my own," said he, "as like you as two blocks, and he's all the pride of my 'art. But the great thing for boys is discipline, sonny—discipline. Now, if you had sailed along of Bill, you wouldn't have stood there to be spoke to twice—not you. That was never Bill's way, nor the way of sich as sailed with him. And here, sure enough, is my mate Bill, with a spy-glass under his arm, bless his old 'art, to be sure. You and me'll just go back into the parlour, sonny, and get behind the door, and we'll give Bill a little surprise—bless his 'art, I say again."

So saying, the stranger backed along with me into the parlour, and put me behind him in the corner, so that we were both hidden by the open door. I was very uneasy and alarmed, as you may fancy, and it rather added to my fears to observe that the stranger was certainly frightened himself. He cleared the hilt of his cutlass and loosened the blade in the sheath; and all the time we were waiting there he kept swallowing as if he felt what we used to call a lump in the throat. At last in strode the captain, slammed the door behind him, without looking to the right or left, and marched straight across the room to where his breakfast awaited him.

"Bill," said the stranger, in a voice that I thought he had tried to make bold and big.

The captain spun round on his heel and fronted us; all the brown had gone out of his face, and even his nose was blue; he had the look of a man who sees a ghost, or the evil one, or something worse, if anything can be; and, upon my word, I felt sorry to see him, all in a moment, turn so old and sick. "Come, Bill, you know me; you know an old shipmate, Bill, surely," said the stranger. The captain made a sort of gasp. "Black Dog!" said he. "And who else?" returned the other, getting more at his ease. "Black Dog as ever was, come for to see his old shipmate Billy, at the 'Admiral Benbow' inn. Ah, Bill, Bill, we have seen a sight of times, us two, since I lost them two talons," holding up his mutilated hand.

"Now, look here," said the captain; "you've run me down; here I am; well, then, speak up: what is it?" "That's you, Bill," returned Black Dog, "you're in the right of it, Billy. I'll have a glass of rum from this dear child here, as I've took such a liking to; and we'll sit down, if you please, and talk square, like old shipmates."

When I returned with the rum, they were already seated on either side of the captain's breakfast table—Black Dog next to the door, and sitting sideways, so as to have one eye on his old shipmate, and one, as I thought, on his retreat.

He bade me go, and leave the door wide open. "None of your keyholes for me, sonny," he said; and I left them together, and retired into the bar.

For a long time, though I certainly did my best to listen, I could hear nothing but a low gabbling; but at last the voices began to grow higher, and I could pick up a word or two, mostly oaths, from the captain.

"No, no, no, no; and an end of it!" he cried once. And again, "If it comes to swinging, swing all, say I." Then all of a sudden there was a tremendous explosion of oaths and other noises—the chair and table went over in a lump, a clash of steel followed, and then a cry of pain, and the next instant I saw Black Dog in full flight, and the captain hotly pursuing, both with drawn cutlasses, and the former streaming blood from the left shoulder. Just at the door, the captain aimed at the fugitive one last tremendous cut, which would certainly have split him to the chine had it not been intercepted by our big signboard of Admiral Benbow. You may see the notch on the lower side of the frame to this day. That blow was the last of the battle. Once out upon the road, Black Dog, in spite of his wound, showed a wonderful clean pair of heels, and disappeared over the edge of the hill in half a minute. The captain, for his part, stood staring at the signboard like a bewildered man. Then he passed his hand over his eyes several times, and at last turned back into the house.

"Jim," says he, "rum;" and as he spoke, he reeled a little, and caught himself with one hand against the wall. "Are you hurt?" cried I. "Rum," he repeated. "I must get away from here. Rum! rum!"

I ran to fetch it; but I was quite unsteadied by all that had fallen out, and I broke one glass and fouled the tap, and while I was still getting in my own way, I heard a loud fall in the parlour, and running in, beheld the captain lying full length upon the floor. At the same instant my mother, alarmed by the cries and fighting, came running down-stairs to help me. Between us we raised his head. He was breathing very loud and hard; but his eyes were closed, and his face a horrible colour.

"Dear, deary me," cried my mother, "what a disgrace upon the house! And your poor father sick!" In the meantime, we had no idea what to do to help the captain, nor any other thought but that he had got his death-hurt in the scuffle with the stranger. I got the rum, to be sure, and tried to put it down his throat; but his teeth were tightly shut, and his jaws as strong as iron. It was a happy relief for us when the door opened and Doctor Livesey came in, on his visit to my father. "Oh, doctor," we cried, "what shall we do? Where is he wounded?"

"Wounded? A fiddle-stick's end!" said the doctor. "No more wounded than you or I. The man has had a stroke, as I warned him. Now, Mrs. Hawkins, just you run up-stairs to your husband, and tell him, if possible, nothing about it. For my part, I must do my best to save this fellow's trebly worthless life; and Jim, you get me a basin."

When I got back with the basin, the doctor had already ripped up the captain's sleeve, and exposed his great sinewy arm. It was tattooed in several places. "Here's luck," "A fair wind," and "Billy Bones his fancy," were very neatly and clearly executed on the forearm; and up near the shoulder there was a sketch of a gallows and a man hanging from it—done, as I thought, with great spirit. "Prophetic," said the doctor, touching this picture with his finger. "And now, Master Billy Bones, if that be your name, we'll have a look at the colour of your blood. Jim," he said, "are you afraid of blood?" "No, sir," said I.

"Well, then," said he, "you hold the basin;" and with that he took his lancet and opened a vein. A great deal of blood was taken before the captain opened his eyes and looked mistily about him. First he recognised the doctor with an unmistakable frown; then his glance fell upon me, and he looked relieved. But suddenly his colour changed, and he tried to raise himself, crying:— "Where's Black Dog?"

"There is no Black Dog here," said the doctor, "except what you have on your own back. You have been drinking rum; you have had a stroke, precisely as I told you; and I have just, very much against my own will, dragged you headforemost out of the grave. Now, Mr. Bones——" "That's not my name," he interrupted.

"Much I care," returned the doctor. "It's the name of a buccaneer of my acquaintance; and I call you by it for the sake of shortness, and what I have to say to you is this: one glass of rum won't kill you, but if you take one you'll take another and another, and I stake my wig if you don't break off short, you'll die—do you understand that?—die, and go to your own place, like the man in the Bible. Come, now, make an effort. I'll help you to your bed for once."

Between us, with much trouble, we managed to hoist him up-stairs, and laid him on his bed, where his head fell back on the pillow, as if he were almost fainting.

"Now, mind you," said the doctor, "I clear my conscience—the name of rum for you is death." And with that he went off to see my father, taking me with him by the arm. "This is nothing," he said as soon as he had closed the door. "I have drawn blood enough to keep him quiet awhile; he should lie for a week where he is—that is the best thing for him and you; but another stroke would settle him."

|

||

|

This website is Copyright © 1999 & 2022 Max Energy Limited, an environmental educational charity.

|