|

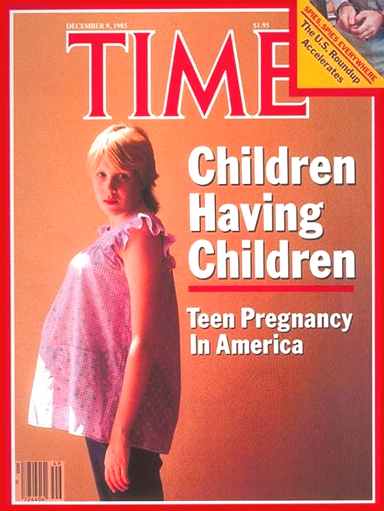

TEENAGE PREGNANCY

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | INVESTORS | MUSIC | NEWS | SOLAR BOATS | SPORT |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Teenage pregnancy is technically defined as occurring when women under the age of 20 become pregnant, although in the U.S. the term usually refers to girls younger than 18 years of age. Barring both medical and physical concerns, problems of teenage pregnancy arise from individual, familial, and social factors. These include but are not limited to: culture, religion, moral values and beliefs, law, education, economic circumstances, lack of support structures such as finding access to health care, contraception, and other resources, and mental and emotional well-being.

Data supporting teen pregnancy as a social issue in developed countries include lower educational levels, higher rates of poverty, and other poorer "life outcomes" in children of teenage mothers. Teenage pregnancy in developed countries is usually outside of marriage, and, for this reason, it carries a social stigma in many communities and cultures.

Global incidence

Industrialized and developing countries have distinctly different incidences of teenage pregnancy. In developed regions, such as North America and Western Europe, teen parents tend to be unmarried and adolescent pregnancy is seen as a social issue.

By contrast, teen parents in developing countries are often wed, and their pregnancy may be welcomed by family and society. However, in these societies, early pregnancy may combine with malnutrition and poor health care to cause medical problems. A report by Save the Children found that, annually, 13 million children are born to women under age 20 worldwide. More than 90% of these births occur to women living in developing countries. Complications of pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of mortality among girls between the ages of 15 and 19 in such areas.

In countries where it is illegal to have intercourse at a young age, such as the United Kingdom and the USA, the state should properly prosecute all offenders, especially those under the age threshold set by the state. But this is not happening. Instead, the state is condoning under age sex by providing children as young as 13 and under with condoms! Is that not like giving them license to fornicate. Talk about mixed messages. The law is the law and it should be upheld to the letter - otherwise why bother having the law in the first place.

The fact the state does not prosecute those under 16 (18 in the US) for sexual activity, is encouraging girls and boys to find older partners, who the state then prosecute. But they don't prosecute the under age girls or boys, just the older partner that the younger person has snagged, usually by posing as an older person on social websites. That being the case, if the state does not present the full facts to the jury as to who was responsible for commissioning the crime, very often only the older partner gets a prison sentence, while the younger person who was actually responsible in the first place - gets away scott free. In our book that does not qualify as a fair trial for the older person as required by Article 6(1) of the European Convention of Human Rights.

Africa

The highest incidence of teenage pregnancy in the world — 143 per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 years — is in sub-Saharan Africa. Women in Africa, in general, get married at much earlier ages than women elsewhere — leading to earlier pregnancies. In Niger, according to the Health and Demographic Survey in 1992, 47% of women aged 20-24 were married before 15 and 87% before 18. 53% of those surveyed also had given birth to a child before the age of 18.

A Save the Children report identified 10 countries where motherhood carried the most risks for young women and their babies. Of these, 9 were in sub-Saharan Africa, and Niger, Liberia, and Mali were the nations where girls were the most at-risk. In the 10 highest-risk nations, more than one in six teenage girls between the ages of 15 to 19 gave birth annually, and nearly one in seven babies born to these teenagers died before the age of one year.

Asia

In the Indian subcontinent, premarital sex is uncommon, but early marriage sometimes means adolescent pregnancy. The incidence of early marriage is higher in rural regions than it is in urbanized areas. Fertility rates in South Asia range from 71 to 119 births per 1000 women aged 15-19. 30% of all Indian induced abortions are performed on women who are under 20.

Other parts of Asia have shown a trend towards increasing age at marriage for both sexes. In South Korea and Singapore, marriage before age 20 has all but disappeared, and, although the occurrence of sexual intercourse before marriage has risen, rates of adolescent childbearing are low at 4 to 8 per 1000. The rate of early marriage and pregnancy has decreased sharply in Indonesia and Malaysia; however, it remains high in comparison to the rest of Asia.

Surveys from Thailand have found that a significant minority of unmarried adolescents are sexually active. Although premarital sex is considered normal behavior for males, particularly with sex workers, it is not always regarded as such for females. Most Thai youth reported that their first sexual experience, whether within or outside of marriage, was without contraception. The adolescent fertility rate in Thailand is relatively high at 60 per 1000. 25% of women admitted to hospitals in Thailand for complications of induced abortion are students. The Thai government has undertaken measures to inform the nation's youth about the prevention of Sexually transmitted diseases and unplanned pregnancy.

According to the World Health Organization, in several Asian countries including Bangladesh and Indonesia, a large proportion (26-37%) of deaths among female adolescents can be attributed to maternal causes.

Europe

Some figures for European countries (1998):

* per 1000 women aged 15-19

The overall trend in Europe since 1970 has been a decreasing total fertility rate, an increase in the age at which women experience their first birth, and a decrease in the number of births among teenagers. However, in the past, teenage mothers in Europe tended to be married, and therefore were less likely to be perceived as a social issue. Some countries, such as Greece and Poland, retain a traditional model of births to married mothers in their late teens.

The rates of teenage pregnancy may vary widely within a country. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the rate of adolescent pregnancy in 2002 was as high as 100.4 per 1000 among young women living in the London Borough of Lambeth, and as low as 20.2 per 1000 among residents in the Midlands local authority area of Rutland. In Italy, the teenage birth rate in central regions is only 3.3 per 1,000, but, in the Mezzogiorno it is 10.0 per 1000.

The U.K, which has the highest teenage birth rate in Europe, also has a higher rate of abortion than most European countries. 80% of young Britons reported engaging in sexual intercourse while still in their teens, although a half of those under 16, and one-third of those between 16 to 19, said they did not use a form of contraception during their first encounter. Less than 10% of British teen mothers are married and a relatively high proportion of them are under the age of 16. Adolescent pregnancy is viewed as a matter of concern by both the British government and the British press. Other countries like Portugal also have a higher percentage of teenage pregnancy and still abortion continues to be illegal, due to the fact that the studies about people's wishes abortion is marked to January of 2007.

In contrast, the Netherlands has a low rate of births and abortions among teenagers. Compared to countries with higher teenage birth rates, the Dutch have a higher average age at first intercourse and increased levels of contraceptive use (including the "double Dutch" method of using both a contraceptive pill and a condom). Nordic countries, such as Denmark and Sweden, also have low rates of teenage birth, but their abortion rates are higher than those of the Netherlands.

In some countries, such as Italy and Spain, the low rate of adolescent pregnancy may be attributed to traditional values and social stigmatization. These countries also have low overall fertility rates.

Teenage birth is associated with disadvantages in later life. Across 13 nations in the European Union, women who gave birth as teenagers are twice as likely to be living in poverty, in comparison to those who wait until they are over 20.

North America

The United States, at 48.8 births per 1,000 women aged 15–19 in 2000, has the highest teen birth rate in the developed world. The rate of abortion among American adolescents is also high. If all pregnancies, including those which end in termination, are taken into account, then the total rate is 83.6 pregnancies per 1,000 girls. However, the trend is decreasing: in 1990, the birth rate was 61.8, and the pregnancy rate 116.9 per thousand. This decline has manifested across all racial groups, although teenagers of African-American, Canadian Aboriginal, and Hispanic (especially Mexican) descent retain a higher rate, in comparison to that of Anglo-Americans and Asian-Americans. The Guttmacher Institute attributed about 25% of the decline to abstinence and 75% to the effective use of contraceptives.

Statistical studies done recently in North America regarding teen pregnancy have involved collecting data on ethnicity, location, and the age and role of the father. Findings show that Missouri and Mississippi have the highest teen pregnancy rates in the U.S., while Massachusetts has the lowest. An inverse correlation has been noted between teen pregnancy rates and the quality of education in a state. A positive correlation, albeit weak, appears between a city's teen pregnancy rate and its average summer night temperature, especially in the Southern U.S. (Savageau, compiler, 1993-1995).

Throughout the U.S., statistical studies show that the average age of the father of a child is inversely related to the age of the mother, if the mother is less than 16 years of age. [Formula: m < 16 − − > 1 / fo < m , where m = mother's age and f = father's age.] This proportionality is less pronounced in Hispanic populations of the U.S., and in Canada, than it is in the U.S. general population. This explains the common observation that groups and support networks for teen fathers typically contain a greater proportion of Hispanics than do similar groups for teen mothers.

The number of births in the U.S. in which the father is younger than 18 and the mother is older is a small percent, and when the father's age is lower than 16, the above equation is reversed. As the age of the father decreases below 16, the average age of the mother decreases as well, although this decrease is low in absolute-value of slope. The Canadian rate in 1998 was 20.2 per 1000. The courts of Canada can legally give judicial marriage consent if the ages of both partners exceed 14, and in the case of pregnancy this consent is often granted. Two American states, Kansas and Georgia, until recently had laws allowing unlimited age of marriage in the case of pregnancy, but these laws are in the process of amendment after three legal cases. (Lisa Clark; Nebraska marriage age evasion cases)

Oceania

In 1998, Australia had a teenage birth rate of 18.4 per 1000, with only 9% married at the time of birth. New Zealand, with teenage birth rate of 29.8 per 1000, has one of the highest in the industrialized world. The rate of adolescent pregnancy is much higher among members of the Māori community at 74 births per 1000 young women.

Information on sexual behaviour in the Pacific Islands is scarce. However, teen pregnancy is considered an emerging problem. In some Pacific island nations, more than 10% of the total births are among teenage mothers.

Causes of teenage pregnancy

Adolescents may lack knowledge of, or access to, conventional methods of preventing pregnancy, perhaps because they're too embarrassed to seek it.

In other cases, contraception is used, but proves to be inadequate. Inexperienced adolescents may use condoms incorrectly or forget to take oral contraceptives. Contraceptive failure rates are higher for teenagers, particularly poor ones, than for older users. Longer term methods such as injections, subcutaneous implants, the vaginal ring, or intrauterine devices last from a month to years and may prevent pregnancy more effectively in women who have trouble following routines, including many young women. The use of more than one contraceptive measure decreases the risk of unplanned pregnancy, and if one is a condom barrier method, the transmission of sexually transmitted disease is also reduced.

According to information available from the Guttmacher Institute, sex by age 20 is the norm across the world. Most teenagers seek love and intimacy in sexual relationships and, in the US, report that they do not feel pressured to have sex by partners or peers.

However, inhibition-reducing drugs and alcohol may encourage unintended sexual activity, and rape is also a factor in a minority of teen pregnancies.

Poverty is associated with increased rates of teenage pregnancy. [9] A girl is also more likely to become a teenage parent if her mother or older sister gave birth in her teens.

According to Jill Francis, of the National Children's Bureau, "There are four main reasons why girls in Britain become pregnant. We don’t give children enough information; we give them mixed messages about sex and relationships; social deprivation means girls are more likely to become pregnant; and girls whose mothers were teenage mums are more likely to do the same".

Laurence Shaw, a U.K. fertility specialist, has suggested that, despite the social stigma attached to teenage pregnancy, it is a natural biological adaptation to begin reproducing during the peak fertile period of the late teens and early twenties. This is the period of time when the fecundity rate (a measure of fertility) is highest, nearing 30%.

There is little evidence to support the common belief that teenage mothers become pregnant to get benefits and council housing. Most knew little about housing or financial aid before they got pregnant and what they thought they knew often turned out to be wrong.

In some societies, early marriage and traditional gender roles are important factors in the incidence of teenage pregnancy.

Public opinion

Opinion polls have also attempted to determine what some of the root causes of teenage pregnancy might be:

Limiting teenage pregnancies

Many health educators have argued that comprehensive sex education would effectively reduce the number of teenage pregnancies, although opponents argue that such education encourages more and earlier sexual activity.

In the UK, the teenage pregnancy strategy, which was run first by the Department of Health and is now based out of the Children, Young People and Families directorate in the Department for Education and Skills, works on several levels to reduce teenage pregnancy and increase the social inclusion of teenage mothers and their families by:

The teenage pregnancy strategy has had mixed success. Although teenage pregnancies have fallen overall, they have not fallen consistently in every region, and in some areas they have increased. There are questions about whether the 2010 target of a 50% reduction on 1998 levels can be met.

In the United States the topic of sex education is the subject of much contentious debate. Some schools provide "abstinence-only" education and virginity pledges are increasingly popular. Most public schools offer “abstinence-plus” programs that support abstinence but also offer advice about contraception. A team of researchers and educators in California have published a list of "best practices" in the prevention of teen pregnancy, which includes, in addition to the previously mentioned concepts, working to "instill a belief in a successful future", male involvement in the prevention process, and designing interventions that are culturally relevant.

The Dutch approach to preventing teenage pregnancy has often been seen as a model by other countries. The curriculum focuses on values, attitudes, communication and negotiation skills, as well as biological aspects of reproduction. The media has encouraged open dialogue and the health-care system guarantees confidentiality and a non-judgmental approach.

In the developing world, programs of reproductive health aimed at teenagers are often small scale and not centrally coordinated, although some countries such as Indonesia and Sri Lanka have a systematic policy framework for teaching about sex within schools. Non-governmental agencies such as the International Planned Parenthood Federation provide contraceptive advice for young women worldwide. Laws against child marriage have reduced but not eliminated the practice. Improved female literacy and educational prospects have led to an increase in the age at first birth in areas such as Iran, Indonesia, and the Indian state of Kerala.

Impact of adolescent pregnancy and parenthood

Several studies have examined the socioeconomic, medical, and psychological impact of pregnancy and parenthood in teens. Life outcomes for teenage mothers and their children vary; other factors, such as poverty or social support, may be more important than the age of the mother at the birth. Many solutions to counteract the more negative findings have been proposed. Teenage parents can use family and community support, social services and child-care support to continue their education and get higher paying jobs as they progress with their education.

Medical outcomes

Maternal and perinatal health is of particular concern among teens who are pregnant or parenting. The worldwide incidence of premature birth and low birth weight is higher among adolescent mothers. Research indicates that pregnant teens are less likely to receive prenatal care, often seeking it in the third trimester, if at all. The Guttmacher Institute reports that one-third of pregnant teens receive insufficient prenatal care and that their children are more likely to suffer from health issues in childhood or be hospitalized than those born to older women.

Many pregnant teens are subject to nutritional deficiencies from poor eating habits common in adolescence, including attempts to lose weight through dieting, skipping meals, food faddism, snacking, and consumption of fast food. Inadequate nutrition during pregnancy is an even more marked problem among teenagers in developing countries.

Complications of pregnancy result in the deaths of an estimated 70,000 teen girls in developing countries each year. Young mothers and their babies are also at greater risk of contracting HIV.

Risks for medical complications are greater for girls 14 years of age and younger, as an underdeveloped pelvis can lead to difficulties in childbirth. Obstructed labour is normally dealt with by Caesarean section in industrialized nations; however, in developing regions where medical services might be unavailable, it can lead to eclampsia, obstetric fistula, infant mortality, or maternal death. For mothers in their late teens, age in itself is not a risk factor, and poor outcomes are associated more with socioeconomic factors rather than with biology.

Socioeconomic and psychological outcomes

Being a young mother can affect one's education. Teen mothers are more likely to drop out of high school. One study in 2001 found that women who gave birth during their teens completed secondary-level schooling 10-12% as often and pursued post-secondary education 14-29% as often as women who waited until age 30.

Young motherhood can affect employment and social class. The correlation between earlier childbearing and failure to complete high school reduces career opportunities for many young women. One study found that, in 1988, 60% of teenage mothers were impoverished at the time of giving birth. Additional research found that nearly 50% of all adolescent mothers sought social assistance within the first five years of their child's life. A study of 100 teenaged mothers in the United Kingdom found that only 11% received a salary while the remaining 89% were unemployed. Most British teenage mothers live in poverty, with nearly half in the bottom fifth of the income distribution.

One-fourth of adolescent mothers will have a second child within 24 months of the first. Factors that determine which are more likely to have a closely-spaced repeat birth include marriage and education: the likelihood decreases with the level of education of the young woman — or her parents — and increases if she gets married .

Early motherhood can affect the psychosocial development of the infant. The occurrence of developmental disabilities and behavioral issues is increased in children born to teen mothers. One study suggested that adolescent mothers are less likely to stimulate their infant through affectionate behaviors such as touch, smiling, and verbal communication, or to be sensitive and accepting toward his or her needs. Another found that those who had more social support were less likely to show anger toward their children or to rely upon punishment.

Poor academic performance in the children of teenage mothers has also been noted, with many of them being more likely than average to fail to graduate from secondary school, be held back a grade level, or score lower on standardized tests. Daughters born to adolescent parents are more likely to become teen mothers themselves. A son born to a young woman in her teens is three times more likely to serve time in prison.

Teen pregnancy and motherhood can have an influence upon younger siblings. One study found that the little sisters of teen mothers were less likely to place emphasis on the importance of education and employment and more likely to accept sexual initiation, parenthood, and marriage at younger ages; little brothers, too, were found to be more tolerant of non-marital and early births, in addition to being more susceptible to high-risk behaviors. An additional study discovered that those with an older sibling who is a teen parent often end up babysitting their nieces and nephews and that young girls placed in such a situation have an increased risk of getting pregnant themselves.

Teenage fatherhood

Teenage fatherhood can also be a challenge. Many feel obliged to support their child, but due to the low levels of state benefits awarded to such couples, in addition to the low quantity of money that they often earn due to their age, are unable to do so fully. Another addition is that being a teenage father is sometimes looked down upon by society and peers.

Teenage pregnancy in popular culture

Teenage pregnancy is referred or alluded to in many songs, including Baby Mama (soul), There Goes My Life (country), In The Ghetto (rock-and-roll), Brenda's Got a Baby (rap) Papa Don't Preach and 1985 (song) (pop).

References

Organizations

Articles

Forums & support sites

The scales of injustice

The government's criminal justice reforms, proposed in the recently published White Paper, are based on a 'single clear priority' to 'rebalance' the criminal justice system 'in favour of the victims of crime' and to 'bring more offenders to justice'. The explicit goal is to make it easier for the prosecution to secure guilty verdicts and to convict more people. This would seem to be at odds with the reality of criminal justice in England and Wales. The prison population stands at an all time high of over 70 thousand and the prosecution already achieves the conviction of over 95 per cent of defendants at magistrates' courts and 87 per cent of defendants in the Crown Court.

The White Paper seems to be to forget that that not all of those brought to trial will be guilty. A reform agenda framed in a language of 'putting the victim first' overlooks the fact that there are many victims of the present criminal justice system. Any human system can make mistakes, and that miscarriages of justice can and do occur. But, just how many miscarriages of justice victims of the present system are there?

We tend to think about miscarriages of justice as rare and exceptional occurrences. Prominent cases such as the Birmingham six, Guildford Four, Bridgewater four, M25 three, Cardiff three, Stephen Downing, and so on create the impression that miscarriages of justice are seen as very much an intermittent, high profile and small scale problem; that there are very few victims in the context of the statistics of all criminal convictions. But there are many more cases than those which receive prominent coverage in the media. Those cases of criminal conviction that are routinely quashed by the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division), or by the Crown Court for convictions previously obtained in the magistrates' court have received no attention at all.

If we pay more attention to these routinely quashed convictions, we find a scale of miscarriage of justice to fundamentally challenges any notion that the current system of criminal justice is weighted too much in favour of the defendant. The Lord Chancellor's Department's statistics on successful appeals against criminal conviction show that in the decade 1989-1999 the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) abated over 8,470 criminal convictions - a yearly average of 770. In addition, there are around 3,500 quashed criminal convictions a year at the Crown Court for convictions obtained at the magistrates' courts. Contrary to popular perceptions, then, wrongful criminal convictions are a normal, everyday feature of the criminal justice system - the system doesn't just sometimes get it wrong, it gets it wrong everyday, of every week, of every month of every year. With the result that thousands of innocent people experience a whole variety of harmful consequences that wrongful criminal convictions engender.

Justice for All also states that there is an 'absolute determination to create a system that meets the needs of society', 'wins the trust of citizens' and 'acquits the innocent'. Accordingly, the government might think about proposing reforms that would counter the causes of the thousands of routine wrongful criminal convictions that occur each year under the present criminal justice system. These (still) include misdirection by judges which is the most common cause of routine successful appeals; unreliable confessions such as in the cases of Robert Downing, the Cardiff Newsagent three, Andrew Evans, and King and Waugh who between them spent almost a century of wrongful imprisonment based on the unreliable confessions of the vulnerable.

Financial and other incentives which created unreliable 'cell confession evidence' that featured most recently in the case of Reg Dudley and Robert Maynard who each served over 20 years of wrongful imprisonment as a consequence of a 'bargain' between the police and an informant who received a reduced sentence for his part in a robbery in exchange for the necessary evidence for conviction; non-disclosure of vital evidence as in the case of John Kamara who also spent 20 years of wrongful imprisonment because over 200 statements were withheld from his defence team; malicious accusations such as in the case of Roy Burnett who spent 15 years of wrongful imprisonment for a rape that the Court of Appeal said 'almost certainly never happened', or Roger Beardmore who spent three years in prison (of a nine year sentence) for the paedophile rape of a young girl who later admitted that she had lied to get her mother's attention; badly conducted defences such as in the case of Mark Day who was convicted for murder with two others despite the fact that he did not know his co-defendants, a fact that his defence failed to bring to the court's attention; and, 'racism' such as in the case of the M25 three, the case in which three black men were wrongly imprisoned for 10 years despite the fact that witnesses had claimed that two of the offenders were white and four of six victims had referred to at least one of the offenders as white. And this is by no means exhaustive list of the causes of injustice.

When thinking about proposing reforms of the criminal justice system to reduce the conviction of the innocent it might also be pertinent to include some of the possible causes of miscarriages of justice that might never feature in the official statistics of successful appeals. Likely candidates include the 'time loss rule', under which when the wrongly imprisoned apply for an appeal they are advised that if their appeal is ultimately unsuccessful it could result in substantial increases to their sentence. The effect of this is to transform what was intended as a minor check on groundless applications into a major barrier in some meritorious cases. There are also the miscarriages of justice that can result from charge, plea and sentence 'bargaining' and the 'parole deal'. All of these induce innocent people to plead guilty to criminal offences that they have not committed and present a 'dark figure' of miscarriages of justice that can never be fully quantified.

It is clear that the present system of criminal justice is, indeed, in urgent need of reform. But this should not be in the direction of a relaxation of the system in favour of obtaining more guilty verdicts and convicting more people. Rather, the present system needs to a reformed in the direction of 're-balancing' it with its stated aims, namely, to safeguard against convicting of the innocent. The present system makes far too many mistakes. Convicting more of those brought to trial will undoubtedly mean making even more mistakes and convicting even more innocent victims.

Michael Naughton is a postgraduate researcher looking at the harmful consequences of miscarriages of justice in the Department of Sociology, University of Bristol.

Send us your views

Email Observer site editor Sunder Katwala at observer@guardianunlimited.co.uk with comments on articles or ideas for future pieces. You can write to the author of this piece at M.Naughton@Bristol.ac.uk.

About Observer Comment Extra

The Observer website carries additional online commentary each week, with articles responding to recent pieces and offering additional coverage of the major issues. Please get in touch if you would like to offer a piece and see Observer Comment for this week's pieces. Online commentaries are also trailed in the print pages of the newspaper.

LINKS and REFERENCE

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR ONE PARENT FAMILIES

Registered

charity no: 230750

In the news

Disclaimer

HUMANS:

OTHER ANIMALS:

A taste for adventure capitalists

Solar Cola - the healthier cola alternative

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This

website

is Copyright © 1999 & 2012 NJK.

The bird |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

AUTOMOTIVE | BLUEBIRD | ELECTRIC CARS | ELECTRIC CYCLES | SOLAR CARS |