|

HORSE BREEDING

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

HOME | BIOLOGY | FILMS | GEOGRAPHY | HISTORY | INDEX | MUSIC | SOLAR BOATS | SPORT | SPONSORS |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The horse must rank high as one of man's best friends. They were transport for us for hundreds of years, bred for speed, hunting and as beasts of burden. They are also rather beautiful animals with a sense of humour. Fortunes have been made and lost on horses and some have become legends, such as that earthy little fighter Seabiscuit. In times of war, a man and horse together, became the cavalry. A horse is also a companion and a rewarding hobby, or indeed a sporting performance creature, which I'm in favour of, provided the horse is not hurt. Either way they are marvelous creatures, but as with any animal you must look after and love them.

Breeding is a serious commitment

Horse breeding is the process of using selective breeding to produce additional individuals of a given phenotype, that is, continuing a breed. Alternatively, a breeder could, using individuals of differing phenotypes, create a new breed, with specific characteristics.

Beyond phenotype (appearance and conformation) of horses, breeders aspire to improve physical performance abilities. This has led to the development of families or bloodlines within breeds that are specialists for excelling in specific events.

An example of this is horses that are bred to excel in a performance event called "Cutting", or separating a cow from a herd and frustrating the cow's strong instinct to rejoin the herd. This event favors horses that are highly trainable, eg - have an ability to learn from repetitive stimuli, that conformationally have short cannons and low hocks to facilitate quick stops and low turns, are muscular and athletic and commonly somewhat short in stature, and who demonstrate an attitude of dominating a cow, known as "cowsense."

Another example would be show hunter horses that are bred to excel in events such as "Hunter Under Saddle," "English Pleasure," or "Hunter On The Flat." This event favors animals that are tall and leggy, who are able to trot and canter smoothly and efficiently while giving the equestrian a comfortable ride, and who have a naturally good jump with bascule and good form.

A show jumper, however, would be bred less for overall form and more for power over fences, speed, scope, and a general carefulness. This favors a lighter horse with a good galloping stride, a powerful and strong hind end, and a good shoulder angle and length of neck.

The male parent of a horse is commonly known as the sire and the female parent as the dam. The quality of the sire is regarded as more important than the quality of the mare in many circles. However, both are equally important, as each gives 50% of the genes. It may even be said that the mare is more important, as the foal often learns habits from its dam when young.

The Thoroughbred industry does not allow AI or surrogate dams

History of horse breeding

The history of horse breeding goes back millenia. Though the precise date is in dispute, humans could have domesticated the horse as far back as approximately 4500 BCE. However, evidence of planned breeding has a more blurry history.

One of the earliest people known to document the breedings of their horses were the Bedouin of the Middle East, the breeders of the Arabian horse. While it is difficult to determine how far back the Bedouin passed on pedigree information via an oral tradition, there were written pedigrees of Arabian horses by A.D. 1330. The Akhal-Teke of West-Central Asia is another breed with roots in ancient times that was also bred specifically for war and racing. The nomads of the Mongolian steppes bred horses for several thousand years as well, and horse herding is still present in modern Mongolia.

The types of horses bred varied with culture and with the times. The uses to which a horse was put also determined its qualities, including smooth amblers for riding, fast horses for carrying messengers, heavy horses for plowing and pulling heavy wagons, ponies for hauling cars of ore from mines, packhorses, carriage horses and many others.

Medieval Europe bred large horses specifically for war, called destriers. These horses were the ancestors of the great heavy horses of today, and their size was preferred not simply because of the weight of the armor, but also because a large horse provided more power for the knight’s lance. Weighting almost twice as much as a normal riding horse, the destrier was a powerful weapon in battle.

On the other hand, during this same time, lighter horses were bred in northern Africa and the Middle East by Muslim warriors, who did not use lances and preferred a faster, cat-like horse than a slower, larger horse. The lighter horse suited the raids and battles of the Bedouins better than a destrier, and allowed them to outmaneuver rather than overpower the enemy. When Muslim warriors and European knights collided in warfare, the heavy knights were frequently outmanuvered. The Europeans, however, made up for the lack of speed of their native breeds by adding hotter blood from captured oriental horses such as the Arabian, Barb and possibly other breeds to their stables. This cross-breeding led both to a nimbler war horse, such as today's Percheron, but also to created a type of horse known as a Courser, which was used as a message horse rather than a war horse.

The need for horses for heavy draft work continued until the industrial revolution and the advent of the automobile. After this time, draft horse numbers then dropped significantly. The animals are today used mainly for pulling and plowing competitions rather than farm work. They have also been used to outcross with lighter breeds, such as the Thoroughbred, to produce a horse more suited for the sport horse disciplines. During the Renaissance, horses were bred not only for war, but for haute ecole riding, derived from the most athletic movements required of a war horse, and popular among the elite nobility of the time. Breeds such as the Lipizzaner were developed from Spanish-bred horses for this purpose, but also became the preferred mounts of cavalry officers, who were derived mostly from the ranks of the military. It was during this time that gunpowder was developed, and so the light cavalry horse, a faster and quicker war horse, was bred for a “shoot and run” tactic rather than the close hand-to-hand fighting seen in the Middle Ages.

After Charles II retook the British throne in 1660, horse racing, which had been banned by Cromwell, was revived. The Thoroughbred was developed 40 years later, bred to be the ultimate racehorse, through the lines of 3 foundation stallions.

In the 1700s, James Burnett Lord Monboddonoted the importance of selecting appropriate parentage to achieve desired outcomes of successive generations. Monboddo worked more broadly in the abstract thought of species relationships and evolution of species. The Thoroughbred breeding hub in Lexington, Kentucky was developed in the late 1700s, and became a mainstay in American racehorse breeding.

The 17th and 18th centuries saw more of a need for fine carriage horses in Europe, bringing in the dawn of the warmblood. The warmblood breeds have been exceptionally good at adapting to changing times, and from their carriage horse beginnings they easily transitioned during the 1900s into a sport horse type. Today’s warmblood breeds, although still used for competitive driving, are more often seen competing in the show jumping or dressage arenas.

The Thoroughbred continues to dominate the horseracing world, although its lines have been more recently used to improve warmblood breeds and to develop sport horses.

The predecessor of the American Quarter Horse was developed in the 1700s, mainly for quarter racing (racing 1/4 of a mile). The breed was later adapted for work in the west, and “cow sense” was particularly bred for as their use for herding cattle increased. However, because there was also a need for animals suitable for sprint racing, the modern Quarter Horse has two distinct types: the sleeker racing type and the stock horse type. The racing type most resembles the finer-boned ancestors of the first racing Quarter Horses, and the type is still used for 1/4-mile races. The stock horse type, used in western events, is bred for a shorter stride, docile temperament, and cow sense.

Deciding to breed a mare

Breeding a horse should be taken seriously, and the owner should be willing to invest the time and money into the endeavor. It is agreed by most that the one area where an owner should not cut costs is the stud fee, which is generally the area in which most amateur breeders try to save money. If a mare owner is not financially able to breed without cutting back on the stud fee, it is oftentimes best to wait to breed the mare.

A mare should not be bred for the sake of it, but instead have valuable qualities to pass on. The mare owner should in an honest and in an unbiased manner consider the mare’s temperament, conformation, performance record, soundness, bloodlines, and health. Only a mare of good quality should be bred. Many times a mare is bred because the mare owner is in love with her, rather than because she is of good quality, producing a disappointing and un-athletic foal. The mare owner has a great responsibility in this aspect.

Mare owners should also recognize the fact that they will probably not make a profit off their breeding. Top breeding farms know where to cut costs, and are producing in bulk, so are better able to make a profit. The average mare owner, however, should generally aim to break even.

Choosing a stallion

The stallion should be chosen to complement the mare, improving on her poorer qualities. A bad crossing between two otherwise superb horses may produce an average foal. However, a good crossing between two above average horses can result in a very nice foal.

Generally, the stallion should have proven himself in the discipline or sport the mare owner wishes to breed for. An owner intending the foal for jumping, therefore, should not breed the mare to a cutting horse or a local backyard stallion that has not competed.

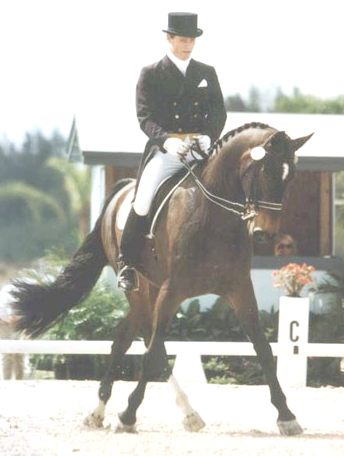

This horse would be suitable to sire horses for the discipline of dressage

Bloodlines are often considered when choosing a stallion, as some bloodlines are known to cross well with others. For example, it is well-known by warmblood breeders that crosses between Donnerhall offspring and Pik Bube offspring produce horses of great quality. If the stallion has not yet proven himself in the breeding shed or while competing, the bloodlines of the horse are often a good indicator of his quality and possible strengths and weaknesses. Some bloodlines are known not only for their athletic ability, but also for a conformational default, poor temperament, or for a medical problem such as roaring or scrotal hemorrhages. Some bloodlines are also extremely marketable, which is an important consideration should the mare owner wish to sell the foal.

The mare owner should consider the size of the stallion, as larger stallions will tend to produce large offspring. A small mare may therefore not be a good cross with a large stallion, as she may have foaling problems due to the great size of her foal. Size may also affect the intended use of a foal. A large horse is often preferred for jumping and eventing, while smaller animals are often considered better cutting horses. If the breeder intends the horse to be used as a child's mount, it is generally advisable to breed for a smaller animal rather than a larger one.

Temperament is often a critical factor to consider when choosing a stallion. This is especially true if the mare owner is intending to breed a horse for a child or amateur, as a good temperament is oftentimes a top priority by nonprofessional horse owners. Poor temperament may also be detrimental to performance when the horse competes, if he is constantly fighting the requests of the rider. However, Thoroughbred racing usually favors horses that are aggressive because they tend to intimidate their opponents while running, and many "mean" racehorses have been excellent on the track.

The conformation of the stallion is of utmost importance. Conformation is easily passed on, and poor conformation may ruin a foal’s chance of ever succeeding in his intended discipline. The stallion should have especially strong conformation in the areas where the mare is weak. So a mare with slightly crooked legs but a powerful hind end might cross well with a stallion with exceptionally straight and well-conformed legs, but a weaker hind end.

The fertility of the stallion should be noted, including the motility of his sperm if he is to be bred using AI. A stallion may not be able to breed naturally, or old age may decrease his performance. It is important not to assume that a stallion with a good competitive performance career is a fertile stallion: the great racehorse Cigar was infertile despite his fantastic career on the track. A mare owner should ask the stud to supply the stallion’s breeding statistics, including the number of mares that he bred and the number that were actually impregnated.

The offspring, or “get,” of a stallion are often excellent indicators of his ability to pass on his characteristics, and the particular traits he actually passes on. Some stallions sire fillies of great abilities but not colts. Secretariat was known as a broodmare-sire: his sons and daughters never performed particularly well, but the offspring of his daughters had talent. Some stallions are fantastic performers but never produce offspring that win in their sport (this has been seen in history with several racehorses, such as Babamist, who produced offspring that excelled in the sport horse disciplines, especially eventing, but never succeeded on the track).

The breed of the stallion is usually secondary when breeding for a sport horse. However, a pure horse is often worth more than one of mixed blood, especially if it is registered. Several disciplines prefer a certain breed of horse as well, such as American Quarter Horses for the western disciplines. Racehorses must usually be of pure blood to race. However, when breeding for sport, performance is considered more strongly than breed.

The cost of breeding

Breeding a horse can be an expensive endeavor, whether breeding a backyard competition horse or the next Olympic medalist. Costs may include:

Stud and booking fees

Stud fees are determined by the quality of the stallion, his performance record, the performance record of his get (offspring), as well as the sport and general market that the animal is standing for.

The highest stud fees are generally for racing Thoroughbreds, which may charge from two to three thousand dollars for a breeding to a new or unproven stallion, to several hundred thousand dollars for a breeding to a stakes winner. Sport horse stallions generally range from $1000 to $3000, although the top stallions may reach $4000 for one breeding. The lowest stud fees may only be $100-$200, but there are trade-offs: the horse will probably be unproven, and probably much less athletic than a horse with a stud fee only $100-$200 more.

As a stallion's career, either performance or breeding, improves, his stud fee tends to increase in proportion. If one or two offspring are especially successful, winning several stakes races or an Olympic medal, the stud fee will generally greatly increase. Younger, unproven stallions will generally have a lower stud fee earlier on in their careers.

An example of a horse that can command hundreds of thousands of dollars in stud fees is A.P. Indy. Since being retired to stud in 1993, A.P. Indy has sired hundreds of stakes winners, most recently 2006 Preakness Stakes winner Bernardini. He is also regarded for his own record and ancestry: he was sired by Triple Crown winner Seattle Slew, AND his dam was sired by Triple Crown winner Secretariat. A.P. Indy himself won the Belmont Stakes in 1992. He currently commands $300,000 per breeding for live cover. [1] [2]

There is oftentimes a booking fee included in the stud fee, which is used to reserve a place in the stallion's upcoming breeding schedule. This generally ranges from $50 to several hundred dollars.

For mares that are not bred "live cover," there is also a collection fee and shipping fee for the semen. This may be a few hundred dollars, depending on the distance and the stud fee of the horse.

To help decrease the risk of financial loss should the mare die or abort the foal while pregnant, many studs have a live foal guarantee (LFG), allowing the owner to have a free breeding to their stallion the next year. However, this is not offered for every breeding.

Covering the mare

There are two general ways to "cover" or breed the mare:

After the mare is bred or artificially inseminated, she is checked 16 days later to see if she “took,” and is pregnant. A second check is usually performed at 28 days. If the mare is not pregnant, she may be bred again during her next cycle.

Live cover

When breeding live cover, the mare is usually boarded at the stud. She is "teased" several times with a stallion that will not breed to her, usually with the stallion being presented to the mare over a barrier. Her reaction to the teaser, whether hostile or passive, is noted. A mare that is in heat will generally tolerate a teaser (although this is not always the case), and may present herself to him, holding her tail to the side. A veterinarian may also determine if the mare is ready to be bred, by ultrasound or palpating daily to determine if ovulation has occurred.

When it has been determined that the mare is ready, both the mare and intended stud will be cleaned. The mare will then be presented to the stallion, usually with one handler controlling the mare and one or more handlers in charge of the stallion. Multiple handlers are preferred, as the mare and stallion can be easily separated should there be any trouble.

The Thoroughbred industry requires all registered foals to be bred through live cover. Artificial fertility treatments, listed below, are not permitted.

Artificial insemination (AI)

AI has several advantages over live cover, and has a very similar conception rate:

A stallion is usually trained to mount a phantom mare, although a live mare may be used, and he is collected using an artificial vagina (AV), which is often heated to simulate the vagina of the mare. The AV has a filter and collection area at one end to collect the semen, which is then processed in a lab. The semen is then chilled or frozen and shipped to the mare owner. When the mare is in heat, a veterinarian introduces the semen directly into her via a syringe and pipette.

Surrogate dams

Often an owner does not want to take a valuable competition mare out of training to carry a foal. This presents a problem, as the mare will usually be quite old by the time she is retired from her competitive career, at which time it is more difficult to impregnate her. Other times, a mare may have physical problems that prevent or discourage breeding. However, there are now several options for breeding these mares. These options also allow a mare to produce multiple foals each breeding season, instead of the usual one. Therefore, mares may have an even greater value for breeding.

POPULAR MAMMALS:

REFERENCE and LINKS:

REFERENCE and LINKS:

Racing and sport links

A taste for adventure capitalists

Solar Cola - a healthier alternative

|