Tutankhamun

was the last pharoah of Egypt.

Tutankhamun (alternately spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, -amon)

was an Egyptian pharaoh betwen 1341 BC – 1323 BC, of the 18th dynasty (ruled ca. 1332 BC – 1323 BC in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. He is popularly referred to as King Tut. His original name, Tutankhaten, means "Living Image of Aten", while Tutankhamun means "Living Image of Amun".

In hieroglyphs, the name Tutankhamun was typically written Amen-tut-ankh, because of a scribal custom that placed a divine name at the beginning of a phrase to show appropriate

reverence. He is possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters, and likely the 18th dynasty king Rathotis who, according to Manetho, an ancient historian, had reigned for nine years — a figure which conforms with Flavius Josephus's version of Manetho's

Epitome.

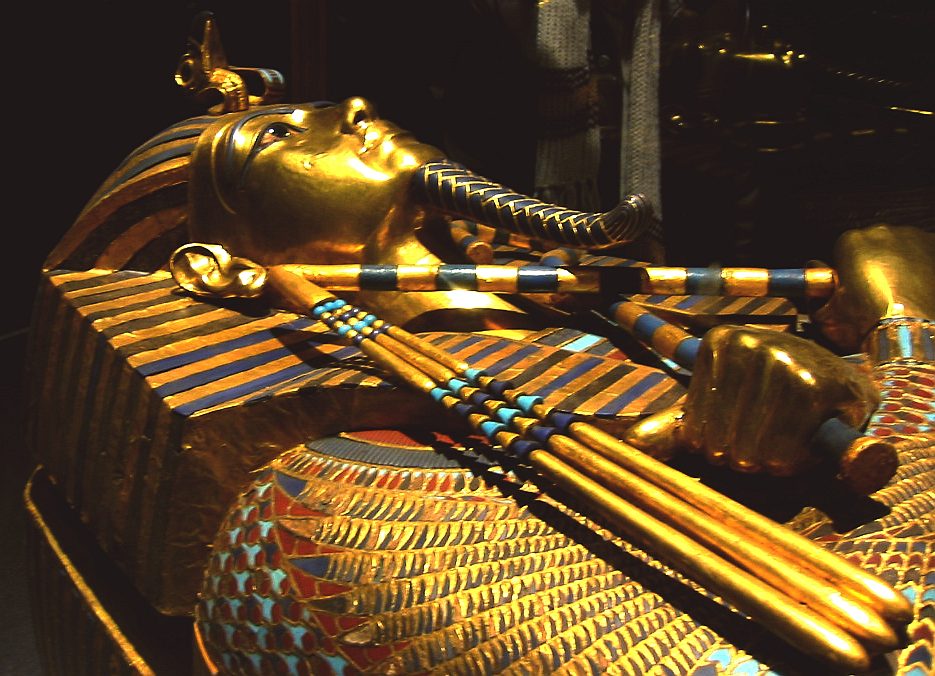

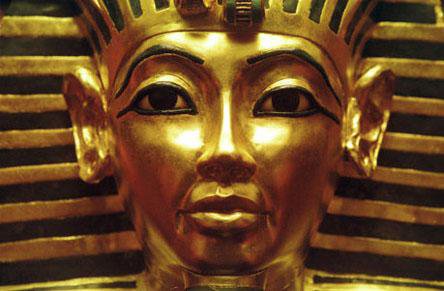

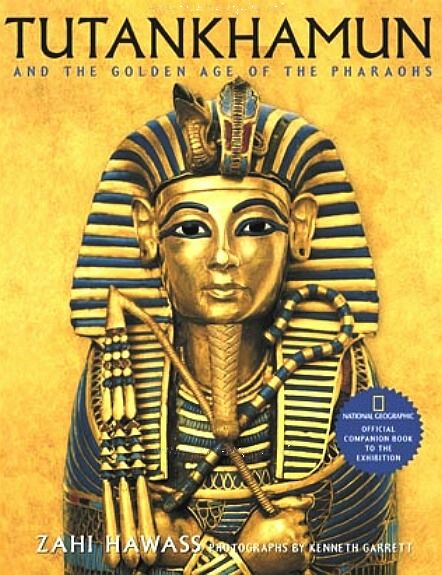

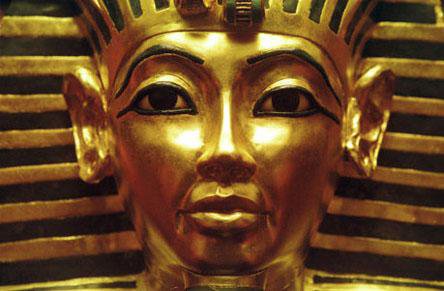

The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter and George Herbert, 5th Earl of

Carnarvon of Tutankhamun's nearly intact tomb received worldwide press coverage. It sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun's burial mask remains the popular symbol. Exhibits of artifacts from his tomb have toured the world. In February 2010, the results of DNA tests confirmed that he was the son of Akhenaten (mummy KV55) and his sister/wife (mummy KV35YL), whose name is unknown but whose remains are positively identified as "The Younger Lady" mummy found in

KV35.

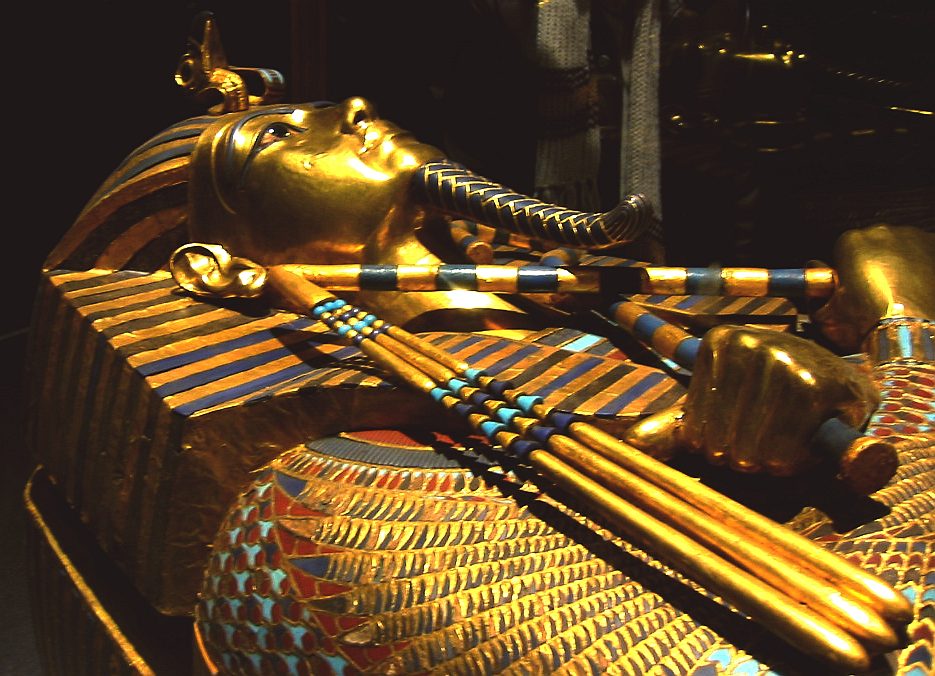

On February 12, 1924, English Egyptologist Howard Carter and his team removed the lid on the third and last sarcophagus of the burial chamber in tomb KV62 revealing the mummy of

Tutankhamun. By February 1923, Carter had already discovered the Burial Chamber of Tutankhamun's tomb hidden in the Valley of the Kings.

Tutankhamun was the 11th pharaoh of Dynasty 18 of the New Kingdom in Ancient Egypt, making his mummy over 3,300 years

old. The discovery of the tomb as a whole was one of the most significant and famous archeological discoveries in modern times. There has been great speculation about the alleged Curse of the Pharaohs and also the actual cause of death of King Tutankhamun since very little data about the young king is

known.

Although most Egyptologists agree that King Tutankhamun, or King Tut (as he is commonly referred to), was the 11th pharaoh during the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom, what is still not exactly clear is to the exact dates of Tut's reign. An educated estimate is that he ruled over Ancient Egypt from about 1346-1355

BCE. After an initial examination of the 3,300 year old mummy, it was estimated that Tut was a teenager of approximately 17–19 years of age when he

died. Since it was believed that Tutankhamun became king as child no more than 10 years old, many refer to him as the "Boy-King" or "Child-King." A majority of his reign was devoted to restoring Egyptian culture, including religious and political policies because Tut's predecessor Akhenaten (recently proven to be Tut's father) had altered many Egyptian cultural aspects during his reign, and one of Tut's many restoration policies included changing the political capital from Akhenaten's Amarna back to

Memphis.

Following the discovery of Tut's mummy, much debate has arisen as to his exact cause of death. This has led to numerous medical studies and procedures performed on his remains, including as recent as 2009. As medical technology advanced throughout the years, new techniques were utilized on the mummy to discover the true age, genealogy, and cause of death of the young pharaoh (is either a war battle wound or chariot fall) so some of the mysteries surrounding the "Boy-King" could finally be put to rest.

Discovery of the mummy

Under the commission of George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, who is commonly called just Lord Carnarvon, Howard Carter and his team set out to Egypt in 1922 to discover the tomb of Tutankhamun, and because of other recent discoveries during that time in a particular area of the Valley of the Kings, Carter believed he had a good idea of where he would find

it. Theodore M. Davis, a contemporary archeologist of Carter, discovered pottery with Tut's name a short distance from where Carter would on November 4, 1922 discover

KV62.

The location at the Valley of the Kings was significant to the New Kingdom because it is where the pharaohs of the time and some other important people to the king were buried. The idea behind burying them there was that is was supposed to be a hidden location in a remote area since tomb robbing was a constant problem during Ancient Egyptian times. Unfortunately the location was not as secret as it was hoped to be, and most of the tombs were broken into and either stolen from or damaged. King Tut's tomb did suffer from some tomb robbing, but overall much of it was left intact and some areas including the burial chamber appeared to be left

unscathed.

Initial examination

On November 11–19, 1925 Dr. Douglas Derry and Dr. Saleh Bey Hamdi along with Carter and other members of the expedition team began to examine the mummy. It was initially very difficult for the team to unwrap the mummy because it appeared the anointing oils that were most likely used during the mummification ceremony had caused the mummy to stick to the tomb. Although the wrappings were in poor condition, it seemed they were of the same material that other kings from the period had been wrapped in. As each layer was removed, the team began to discover many fine objects were wrapped between the layers all over Tut's body. Some of these objects included gold jewelry, jumping castels, and pieces of armor. Once the layers had been removed and they could finally begin to examine the actual corpse, they began to take anatomical notes of the body. He was determined to be approximately 5 feet, 6 inches and have had a slight build. He had a slightly curved spine, small bone fragments were found from the skull, a lesion was discovered on his left side of the jaw, and because the chest cavity was filled with wrappings, no further studying was done on

it.

Later studies

Since Carter's discovery and examination of the mummy there have been three important further examinations done with more modern medical techniques and equipment.

X-rays done in 1968

In 1968, R. G. Harrison, a professor of anatomy, used a portable x-ray machine to get a better look at the internal structures of the mummy to better determine age and cause of death of Tutankhamun. One of the most abnormal findings was the sternum (breastbone) and most parts of the frontal ribs were missing. Removing these bones was not part of the normal mummification process, which lead Harrison to believe they might have been removed because they were badly damaged before his death. Harrison quickly discovered that Carter was not as careful as many of his personal notes had claimed. The mummy was not re-wrapped after 1926, which led to more deterioration due to the extremely hot external elements over the forty-two years. Also many of the limbs had been amputated in the body in order to remove some of the jewelry. Both hands were cut off, both legs were removed from the pelvis, and the head was severed from the body in order to get the mask off. Even more remarkable is

that the king's right ear and penis were missing, but photographs from Carter show they were both present during his examination. Harrison believed the slight curve in the spine and small bone fragments might have been the result of the embalming process. The lesion on the left jaw showed signs of healing occurred before Tut's death and one of his legs had been broken, but it could not be determined if it happened naturally or as a result of the embalming or Carter's examination. The fact that skull fragments were discovered led many to assume the king was murdered by a blow to the head, but the x-ray could not support or discredit this

theory.

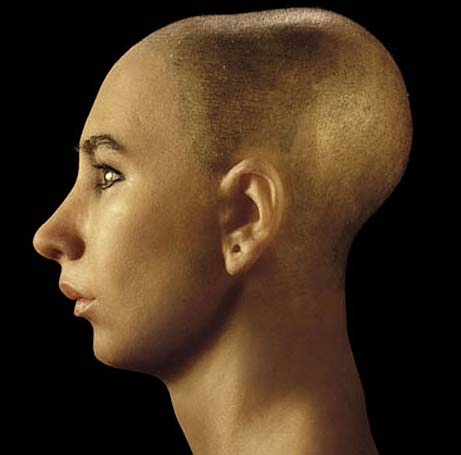

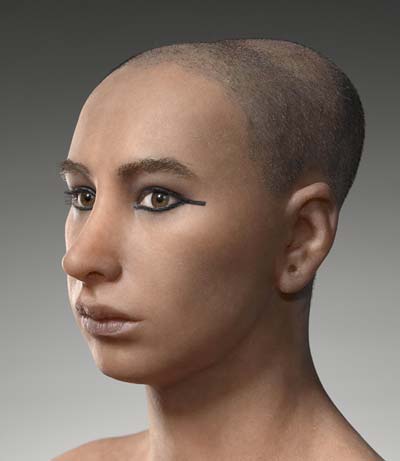

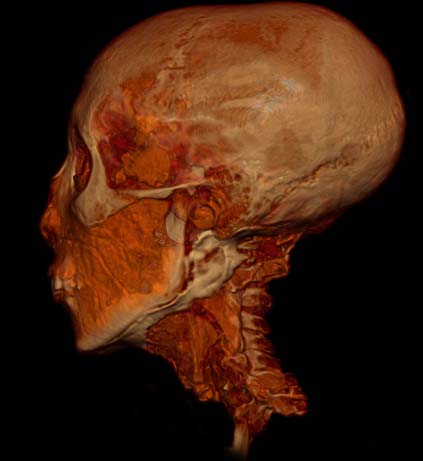

CT Scan done in 2005

On January 15, 2005, under the direction of Dr. Madeeha Khattab, the Dean of the School of Medicine at Cairo University, Tutankhamun was removed from the tomb and a CT scan (computerized tomography) was performed on the mummy. The scan allowed for accurate forensic reconstruction of Tut's body and face, as well as further evidence of his cause of death. Testing showed there was no traumatic injury to the head, he had a small cleft palate that went probably unnoticed, and the elongated shape of his skull was within the normal range and appeared to be a family trait after some studies were done on mummies that were believed to have been related to Tut. Based on bone maturity and his wisdom teeth, Tutankhamun was confirmed to be 19 years old at the time of his death. The CT scan proved Tut was in good health and did not show any signs of disease that would have affected his build. Study concluded Tut was not murdered from traumatic head injury, but a non-violent murder could still not be ruled out. There appeared to be no indication of any long-term

disease.

DNA testing done from 2007-2009

From September 2007 to October 2009, 11 royal mummies of the New Kingdom's 18th Dynasty have undergone extensive genetic and radiological testing. A team of doctors, under the leadership of Dr. Zahi Hawass, took DNA samples from bone tissue of the 11 mummies to determine a family pedigree and to determine if any familial, pathological diseases caused Tutankhamun's death. The study was able to provide a 5-generation pedigree, and the KV55 mummy and KV35YL mummy were identified as Tut's parents. KV55 is believed to have contained the body of Ahkenhaten and in KV35, a young lady mummy was discovered and believed to be either Kiya or Nefertiti. It was discovered that Tutankhamun's family had a large number of irregularities. Four of the mummies, including Tut, were shown to have had Malaria tropica. Based on all the data, the study concluded the most likely cause of death for the young king was the combination of avascular necrosis and Malaria. The fact that a cane and Ancient Egyptian-style medicines were found in the tomb backed up Hawass's claim that Tut suffered from a walking

impairment.

Popular speculation

Since the discovery of Tutankhamun's mummy, there has been a lot of speculation and theories[by whom?] on the exact cause of death, which until recent studies had been hard to prove with the evidence and data available. While it was a widely debated topic for many Egyptologists, it had also spread to the general public as popular culture has come up with many conspiracy theories that played out in movies, TV shows, and fictional books. Author James Patterson has even recently written his own take in his new book, The Murder of King

Tut. There are many educated and respected Egyptologists as well as trained professionals in other

fields who have devoted a lot of time researching Tut and who have varying beliefs to Tut's cause of death. Some have stood by their theories even in light of new evidence. Some of the theories are better known and supported than others.

Bob Brier

Bob Brier, an Egyptologist who specializes in paleopathology, uses evidence of the condition of the mummy including the skull fragments as well as other historical data from the period to illustrate his belief that King Tut was murdered by his Grand Vizor, who stood the chance to gain the most when Tut

died.

Paul Doherty

Paul Doherty, a British historian who has written many articles and books on the subject of Ancient Egypt, uses physical evidence collected about the mummy to suggest his theory that Tut suffered from Marfan Syndrome. He believed Tut must have genetically inherited the disease, and it eventually led to his

death.

Christine El Mahdy

Christine El Mahdy, an Egyptologist, argues that Tut died of natural causes, which she believes was most likely a tumor of some sort. She uses the original assumption from Carter's examination that Tut had a quick burial ceremony since some elements of the mummification appeared rushed, as proof that he needed to be buried quickly following his unexpected death because the man who was next in line for the throne wanted to avoid a power struggle that would have occurred if the burial process took too long. By speeding up the burial ceremony, the new pharaoh maintained order in

Egypt.

Michael R. King

Much like Paul Doherty, Michael R. King, a detective with a lot of experience studying King Tut, and FBI profiler Gregory M. Cooper, came together with an actual Egyptologist to form their own theory which was Tut was murdered. With the use of forensic evidence and their extensive backgrounds in Criminology, they came to the conclusion that Tut was likely murdered by one of his closest advisors, Ay. Ay did succeed Tutankhamun on the throne, so they used that as the motivation for the

murder.

Christian Timmann and Christian Meyer

Christian Timmann and Christian Meyer, medical doctors and scientists at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg, Germany, have used the most recent medical testing done on Tutankhamun's mummy by Dr. Hawass, and have come to the conclusion that Tut did not die from a combination of bone disease and malaria, but instead had Sickle Cell Disease. Dr. Timmann and Dr. Meyer believed the Sickle Cell Disease turned fatal when Tut also contracted severe malaria that was rampant in Ancient Egypt during Tut's era. Tut is expected to have been homozygous recessive for the sickle cell gene thus making him not immune to severe malaria, which would have been

fatal.

Significance of Discovery

The royal bloodline that Tutankhamun's family shared, ended with the death of the young pharaoh, and with that came a question of the legitimacy of the following

rulers. King Tut's tomb was the only one discovered that was not very disturbed by grave robbers, which allowed Carter to uncover many artifacts and the untouched mummy. It gave amazing insight into the royal burials, mummification, and tombs of the New Kingdom's 18th

Dynasty. Since its discovery and wide-spread popularity, it has led to DNA testing done on it and other mummies from the time period that now give a proven family tree for many of the royalty during the 18th

Dynasty. Since his death was unexpected and either poorly recorded or simply the records were lost over the years, with the discovery of his mummy and advances in modern technology, there is now strong and supported evidence as to Tut's death, and with that one of Egypt's most popular mysteries appears to have been solved.

Current Location

As of October 2010, the mummy of Tutankhamun can be found in his original resting spot in KV62 in the Valley of the Kings. If one visits the location at the ancient city of Thebes, there are tours that will take people into the tomb where they can see the actual sarcophagus that holds Tut's mummy.

Bibliography

Brier, Bob. The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story. New York: Berkley Trade, 2010.

Carter, Howard. The Tomb of Tutankhamen. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 1923.

Carter, Howard, and A. C. Mace. The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen. New York: Dover Publications, 1977.

Carter, Howard. (Sept. 1925- May 1926). "Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation." Howard Carter's Diaries.

Oxford: Griffith Institute.

23 October 2010.

Carter, Howard. (1927). Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen Vol. 2: The Burial Chamber. London: Cassell & Company Ltd.

Doherty, P. C. The Mysterious Death of Tutankhamun. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2002.

Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. "Tutankhamun". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Ed. Donald B. Redford.

El Mahdy, Christine. Tutankhamen: The Life and Death of the Boy-King. New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 2001.

Harrison, R.G. and Abdalla, A.B.. (1972) "The Remains of Tutankhamun". Antiquity. Vol.46: 8–14.

Hawass, Zahi, Yehia Z Gad, and Et Al. "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family." JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 303.7 (17 February 2010): 638-47. OvidSP. Wolter Kluwer Health.

James, T.G.H. "Carter, Howard" The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Ed. Donald B. Redford.

King, Michael R., Gregory M. Cooper, and Don DeNevi. Who Killed King Tut?: Using Modern Forensics to Solve a 3,300-Year-Old Mystery: With New Data on the Egyptian CT Scan. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 2006.

Mace, Arthur C. "Work at the Tomb of Tutankhamun." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 33.2 (1975): 96-108. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Web. 23 Oct. 2010.

Timmann, Christian MD, and Christian G. MD Meyer. "King Tutankhamun’s Family and Demise." JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 303.24 (23/30 June 2010): 2473. OvidSP. Wolter Kluwer Health.

Williams, A. R. "Modern Technology Reopens the Ancient Case of King Tut." National Geographic 207.6 (June 2005): 2-21. WilsonWeb.