|

Witchcraft (also called witchery or

spellcraft) is the use of magical faculties, most commonly for religious, divinatory or medicinal purposes. This may take many forms depending on cultural context.

The belief in and the practise of magic has been present since the earliest human cultures and continues to have an important religious and medicinal role in many cultures today.

"Magic is central not only in 'primitive' societies but in 'high cultural' societies as well..."

The concept of witchcraft as harmful is often treated as a cultural ideology providing a scapegoat for human misfortune. This was particularily the case in Early Modern Europe where witchcraft came to be seen as part of a vast diabolical conspiracy of individuals in league with the Devil undermining Christianity, eventually leading to large-scale witch-hunts, especially in Protestant Europe.

Witch hunts continue to this day with tragic consequences. Since the mid-20th century Witchcraft has become the designation of a branch of contemporary Paganism, it is most notably practised in the Wiccan traditions, some of whom claim to practice a revival of

pre-Abrahamic spirituality.

AFRICAN

WITCHDOCTORS

The term witch doctor, a common translation for the South African Zulu word inyanga, has been misconstrued to mean "a healer who uses witchcraft" rather than its original meaning of "one who diagnoses and cures maladies caused by witches".

In Southern African traditions, there are three classifications of somebody who uses magic. The thakathi is usually improperly translated into English as "witch", and is a spiteful person who operates in secret to harm others. The sangoma is a diviner, somewhere on a par with a fortune teller, and is employed in detecting illness, predicting a person's future (or advising them on which path to take), or identifying the guilty party in a crime. She also practices some degree of medicine. The inyanga is often translated as "witch doctor" (though many Southern Africans resent this implication, as it perpetuates the mistaken belief that a "witch doctor" is in some sense a practitioner of malicious magic). The inyanga's job is to heal illness and injury and provide customers with magical items for everyday use. Of these three categories the thakatha is almost exclusively female, the sangoma is usually female, and the inyanga is almost exclusively male.

Much of what witchcraft represents in Africa has been susceptible to misunderstandings and confusion, thanks in no small part to a tendency among western scholars since the time of the now largely discredited Margaret Murray to approach the subject through a comparative lens vis-a-vis European witchcraft. Okeja argues that witchcraft in Africa today plays a very different social role than in Europe of the past—or present—and should be understood through an African rather than post-colonial Western lens.

In some Central African areas, malicious magic users are believed by locals to be the source of terminal illness such as AIDS and cancer. In such cases, various methods are used to rid the person from the bewitching spirit, occasionally physical and psychological abuse. Children may be accused of being witches, for example a young niece may be blamed for the illness of a relative. Most of these cases of abuse go unreported since the members of the society that witness such abuse are too afraid of being accused of being accomplices. It is also believed that witchcraft can be transmitted to children by feeding. Parents discourage their children from interacting with people believed to be witches.

As of 2006, between 25,000 and 50,000 children in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, had been accused of witchcraft and thrown out of their homes. These children have been subjected to often-violent abuse during exorcisms, sometimes supervised by self-styled religious pastors. Other pastors and Christian activist strongly oppose such accusations and try to rescue children from their unscrupulous colleagues. The usual term for these children is enfants sorciers (child witches) or enfants dits sorciers (children accused of witchcraft). In 2002, USAID funded the production of two short films on the subject, made in Kinshasa by journalists Angela Nicoara and Mike Ormsby.

In Ghana, women are often accused of witchcraft and attacked by neighbours. Because of this, there exist six witch camps in the country where women suspected of being witches can flee for safety. The witch camps, which exist solely in Ghana, are thought to house a total of around 1000 women. Some of the camps are thought to have been set up over 100 years ago. The Ghanaian government has announced that it intends to close the camps and educate the population regarding the fact that witches do not exist.

In April 2008, in Kinshasa, the police arrested 14 suspected victims (of penis snatching) and sorcerers accused of using black magic or witchcraft to steal (make disappear) or shrink men's penises to extort cash for cure, amid a wave of panic. Arrests were made in an effort to avoid bloodshed seen in Ghana a decade ago, when 12 alleged penis snatchers were beaten to death by mobs. While it is easy for modern people to dismiss such reports, Uchenna Okeja argues that a belief system in which such magical practices are deemed possible offer many benefits to Africans who hold them. For example, the belief that a sorcerer has "stolen" a man's penis functions as an anxiety-reduction mechanism for men suffering from impotence while simultaneously providing an explanation that is consistent with African cultural beliefs rather than appealing to Western scientific notions that are tainted by the history of colonialism (at least for many Africans).

It was reported on May 21, 2008 that in Kenya, a mob had burnt to death at least 11 people accused of witchcraft. In Tanzania in 2008, President Kikwete publicly condemned witchdoctors for killing albinos for their body parts, which are thought to bring good luck. 25 albinos have been murdered since March 2007. In the Meatu district of Tanzania, half of all murders are “witch-killings”., while particularly albinos are often murdered for their body parts on the advice of witch doctors in order to produce powerful amulets that are believed to protect against witchcraft and make the owner prosper in life.

In the Nigerian states of Akwa Ibom and Cross River about 15,000 children branded as witches and most of them end up abandoned and abused on the streets. In Gambia, about 1,000 people accused of being witches were locked in detention centers in March 2009 and forced to drink a dangerous hallucinogenic potion, human rights organization Amnesty International said. Every year, hundreds of people in the Central African Republic are convicted of witchcraft.

Complementary remarks about witchcraft by a native Congolese initiate: "From witchcraft ... may be developed the remedy (kimbuki) that will do most to raise up our

country." "Witchcraft ... deserves respect ... it can embellish or redeem (ketula evo vuukisa)." "The ancestors were equipped with the protective witchcraft of the clan (kindoki kiandundila kanda). ... They could also gather the power of animals into their hands ... whenever they needed. ... If we could make use of these kinds of witchcraft, our country would rapidly progress in knowledge of every kind." "You witches (zindoki) too, bring your science into the light to be written down so that ... the benefits in it ... endow our race."

Among the Mende (of Sierra Leone), trial and conviction for witchcraft has a beneficial effect for those convicted. "The witchfinder had warned the whole village to ensure the relative prosperity of the accused and sentenced ... old people. ... Six months later all of the people ... accused, were secure, well-fed and arguably happier than at any [previous] time; they had hardly to beckon and people would come with food or whatever was needful. ... Instead of such old and widowed people being left helpless or (as in Western society) institutionalized in old people's homes, these were reintegrated into society and left secure in their old age ... . ... Old people are 'suitable' candidates for this kind of accusation in the sense that they are isolated and vulnerable, and they are 'suitable' candidates for 'social security' for precisely the same reasons."

In Nigeria, several Pentecostal pastors have mixed their evangelical brand of Christianity with African beliefs in witchcraft to benefit from the lucrative witch finding and exorcism business—which in the past was the exclusive domain of the so-called witch doctor or traditional healers. These pastors have been involved in the torturing and even killing of children accused of witchcraft. Over the past decade, around 15,000 children have been accused, and around 1,000 murdered. Churches are very numerous in Nigeria, and competition for congregations is hard. Some pastors attempt to establish a reputation for spiritual power by "detecting" child witches, usually following a death or loss of a job within a family, or an accusation of financial fraud against the pastor. In the course of "exorcisms", accused children may be starved, beaten, mutilated, set on fire, forced to consume acid or cement, or buried alive. While some church leaders and Christian activists have spoken out strongly against these abuses, many Nigerian churches are involved in the abuse, although church administrations deny knowledge of it.

In Malawi it is also common practice to accuse children of witchcraft and many children have been abandoned, abused and even killed as a result. As in other African countries both African traditional healers and their Christian counterparts are trying to make a living out of exorcising children and are actively involved in pointing out children as witches. Various secular and Christian organizations are combining their efforts to address this problem.

WITCHFINDER

GENERAL

ddWitchfinder General is a 1968 British horror film directed by Michael Reeves and starring Vincent Price, Ian Ogilvy, and Hilary Dwyer. The screenplay was by Reeves and Tom Baker based on Ronald Bassett's novel of the same name. Made on a low budget of under £100,000, the movie was co-produced by Tigon British Film Productions and American International Pictures. The story details the heavily fictionalized murderous witch-hunting exploits of Matthew Hopkins, a 17th-century English lawyer who claimed to have been appointed as a "Witch Finder Generall" by Parliament during the English Civil War to root out sorcery and

witchcraft. The film was retitled The Conqueror Worm in the United States in an attempt to link it with Roger Corman's earlier series of Edgar Allan Poe-related films starring Price—although this movie has nothing to do with any of Poe's stories, and only briefly alludes to his poem.

Director Reeves featured many scenes of intense onscreen torture and violence that were considered unusually sadistic at the time. Upon its theatrical release throughout the spring and summer of 1968, the movie's gruesome content was met with disgust by several film critics in the UK, despite having been extensively censored by the British Board of Film Censors. In the U.S., the film was shown virtually intact and was a box office success, but it was almost completely ignored by reviewers.

The film has gradually developed a large cult following, partially attributable to Reeves's 1969 death from a drug overdose at the age of 25, only nine months after Witchfinder's release. Over the years, several prominent critics have championed the film, including J. Hoberman, Danny Peary, and Derek Malcolm. In 2005, the magazine Total Film named Witchfinder General the 15th greatest horror film of all time.

PLOT

The year is 1645 - the middle of the English Civil War. Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price), an opportunist and witchhunter, takes advantage of the breakdown in social order to impose a reign of terror on East Anglia. Hopkins and his assistant, John Stearne (Robert Russell), visit village after village, brutally torturing confessions out of suspected witches. They charge the local magistrates for the work they carry out.

Richard Marshall (Ian Ogilvy) is a young Roundhead. After surviving a brief skirmish and killing his first enemy soldier (and thus saving the life of his Captain), he rides home to Brandeston, Suffolk, to visit his lover Sara (Hilary Dwyer). Sara is the niece of the village priest, John Lowes (Rupert Davies). Lowes gives his permission to Marshall to marry Sara, telling him there is trouble coming to the village and he wants Sara far away before it arrives. Marshall asks Sara why the old man is frightened. She tells him they have been threatened and become outcasts in their own village. Marshall vows to Sara, "rest easy and no-one shall harm you. I put my oath to that." At the end of his army leave, Marshall rides back to join his regiment, and chances upon Hopkins and Stearne on the path. Marshall gives the two men directions to Brandeston then rides on.

In Brandeston, Hopkins and Stearne immediately begin rounding up suspects. Lowes is thrown into a cell and tortured. He has needles stuck into his back (in an attempt to locate the so-called "Devil's Mark"), and is about to be killed, when Sara stops Hopkins by offering him sexual favours in exchange for her uncle's safety. However, soon Hopkins is called away to another village. Stearne takes advantage of Hopkins' absence by raping Sara. When Hopkins returns and finds out what Stearne has done, Hopkins will have nothing further to do with the young woman. He instructs Stearne to begin torturing Lowes again. Shortly before departing the village, Hopkins and Stearne execute Lowes and two women.

Marshall returns to Brandeston and is horrified by what has happened to Sara. He vows to kill both Hopkins and Stearne. After "marrying" Sara in a ceremony of his own devising and instructing her to flee to Lavenham, he rides off by himself. In the meantime, Hopkins and Stearne have become separated after a Roundhead patrol attempts to commandeer their horses. Marshall locates Stearne, but after a brutal fight, Stearne is able to escape. He reunites with Hopkins and informs him of Marshall's desire for revenge.

Hopkins and Stearne enter the village of Lavenham. Marshall, on a patrol to locate the King, learns they are there and quickly rides to the village with a group of his soldier friends. Hopkins, however, having earlier learned that Sara was in Lavenham, has set a trap to capture Marshall. Hopkins and Stearne frame Marshall and Sara as witches and take them to the castle to be interrogated. Marshall watches as needles are repeatedly jabbed into Sara's back, but he refuses to confess to witchcraft, instead vowing again to kill Hopkins. He breaks free from his bonds at the same time that his army compatriots approach their place of confinement. Marshall grabs an axe and repeatedly strikes Hopkins. The soldiers enter the room and are horrified to see what their friend has done. One of them puts the mutilated but still living Hopkins out of his misery by shooting him dead. Marshall's mind snaps and he shouts, "You took him from me! You took him from me!" Sara, also apparently on the brink of insanity, screams uncontrollably over and over again.

HISTORICAL ACCURACY

While some reviewers have praised the film for its ostensible "historical accuracy", others have strongly questioned its adherence to historical fact. Dr. Malcolm Gaskill, Fellow and former Director of Studies in history at Churchill College, Cambridge, and author of Witchfinders: A 17th-Century English Tragedy, critiqued the film for the Channel 4 History website, calling it "a travesty of historical truth." While acknowledging that "there is much to be said in favour of Witchfinder General–but as a film, not as history", based purely on its level of historical accuracy Gaskill gave the film "3 stars" on a scale of 0–10.

Gaskill had several complaints regarding the film's "distortions and flights of fancy". While Hopkins and his assistant John Stearne really did torture, try and hang John Lowes, the vicar of Brandeston, Gaskill notes that other than those basic facts the film's narrative is "almost completely fictitious." In the movie, the fictional character of Richard Marshall pursues Hopkins relentlessly to death, but in reality the "gentry, magistrates and clergy, who undermined his work in print and at law" were in pursuit of Hopkins throughout his (brief) murderous career, as he was never legally sanctioned to perform his witch hunting duties. And Hopkins wasn't axed to death, he "withered away from consumption at his Essex home in 1647". Vincent Price was 56 when he played Hopkins, but "the real Hopkins was in his 20s". According to Gaskill, one of the film's "most striking errors is its total omission of court cases: witches are simply tortured, then hanged from the nearest tree."

The

Parsonage in Salem Village, where the witch trials took place in 1692

WITCH

HUNTS

A witch-hunt is a search for witches or evidence of witchcraft, often involving moral panic, or mass hysteria. Before 1750 it was legally sanctioned and involving official witchcraft trials. The classical period of witchhunts in Europe and North America falls into the Early Modern period or about 1480 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 40,000 to 60,000 executions.

The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In the Kingdom of Great Britain, witchcraft ceased to be an act punishable by law with the Witchcraft Act of 1735. In Germany, sorcery remained punishable by law into the late 18th century. Contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from Sub-Saharan Africa, India and Papua New Guinea. Official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon. The term "witch-hunt" since the 1930s has also been in use as a metaphor to refer to moral panics in general (frantic persecution of perceived enemies). This usage is especially associated with the Second Red Scare of the 1950s, with the McCarthyist persecution of communists in the United States.

EARLY MODERN EUROPE

The witch trials in Early Modern Europe came in waves and then subsided. There were trials in the 15th and early 16th centuries, but then the witch scare went into decline, before becoming a major issue again and peaking in the 17th century. What had previously been a belief that some people possessed supernatural abilities (which were sometimes used to protect the people) now became a sign of a pact between the people with supernatural abilities and the devil. To justify the killings, Protestant Christianity and its proxy secular institutions deemed witchcraft as being associated to wild Satanic ritual parties in which there was much naked dancing, and cannibalistic infanticide. It was also seen as heresy for going against the first of the ten commandments (You shall have no other gods before me) or as violating majesty, in this case referring to the divine majesty, not the worldly.

Witch-hunts were seen across early modern Europe, but the most significant area of witch-hunting in modern Europe is often considered to be central and southern Germany. Germany was a late starter in terms of the numbers of trials, compared to other regions of Europe. Witch-hunts first appeared in large numbers in southern France and Switzerland during the 14th and 15th centuries. The peak years of witch-hunts in southwest Germany were from 1561 to 1670. The first major persecution in Europe, when witches were caught, tried, convicted, and burned in the imperial lordship of Wiesensteig in southwestern Germany, is recorded in 1563 in a pamphlet called "True and Horrifying Deeds of 63 Witches".

In Denmark, the burning of witches increased following the reformation of 1536. Christian IV of Denmark, in particular, encouraged this practice, and hundreds of people were convicted of witchcraft and burnt. In England, the Witchcraft Act of 1542 regulated the penalties for witchcraft. In the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, over 70 people were accused of witchcraft on account of bad weather when James VI of Scotland, who shared the Danish king's interest in witch trials, sailed to Denmark in 1590 to meet his betrothed Anne of Denmark. The Pendle witch trials of 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history.

Witch hysteria also erupted in the Americas. In 1645, 46 years before the Salem witch trials, Springfield, Massachusetts experienced America's first accusations of witchcraft when husband and wife, Hugh and Mary Parsons, accused each other of witchcraft. At America's first witch trial, Hugh was found innocent, while Mary was acquitted of witchcraft but sentenced to be hanged for the death of her child. She died in prison. About eighty people throughout England's Massachusetts Bay Colony were accused of practicing witchcraft, thirteen women and two men were executed in a witch-hunt that lasted throughout New England from 1645–1663. The Salem witch trials followed in 1692–93.

Once a case was brought to trial, the prosecutors hunted for accomplices. Magic was not considered to be wrong because it failed, but because it worked effectively for the wrong reasons. Witchcraft was a normal part of everyday life. Witches were often called for, along with religious ministers, to help the ill or to deliver a baby. They held positions of spiritual power in their communities. When something went wrong, no one questioned the ministers or the power of the witchcraft. Instead, they questioned whether the witch intended to inflict harm or not.

SALEM

WITCH TRIALS

In Salem Village in the winter months of 1692, Betty Parris, age 9, and her cousin Abigail Williams, age 11, the daughter and niece, respectively, of Reverend Parris, began to have fits described as "beyond the power of Epileptic Fits or natural disease to effect" by John Hale, minister in nearby Beverly.

The girls screamed, threw things about the room, uttered strange sounds, crawled under furniture, and contorted themselves into peculiar positions, according to the eyewitness account of Rev. Deodat Lawson, a former minister in the town. The girls complained of being pinched and pricked with pins. A doctor, historically assumed to be William Griggs, could find no physical evidence of any ailment. Other young women in the village began to exhibit similar behaviors. When Lawson preached in the Salem Village meetinghouse, he was interrupted several times by outbursts of the afflicted.

The first three people accused and arrested for allegedly afflicting Betty Parris, Abigail Williams, 12-year-old Ann Putnam, Jr., and Elizabeth Hubbard were Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and Tituba. The accusation by Ann Putnam Jr. is seen by historians as evidence that a family feud may have been a major cause of the Witch Trials. Salem was the home of a vicious rivalry between the Putnam and Porter families. The people of Salem were all engaged in this rivalry. Salem citizens would often engage in heated debates that would escalate into full fledged fighting, based solely on their opinion regarding this feud.

Sarah Good was a homeless beggar and known to beg for food and shelter from neighbors. She was accused of witchcraft because of her appalling reputation. At her trial, Good was accused of rejecting the puritanical expectations of self-control and discipline when she chose to torment and “scorn [children] instead of leading them towards the path of salvation".

Sarah Osborne rarely attended church meetings. She was accused of witchcraft because the puritans believed that Osborne had her own self-interests in mind following her remarriage to an indentured servant. The citizens of the town of Salem also found it distasteful when she attempted to control her son's inheritance from her previous marriage.

Tituba, as a slave of a different ethnicity than the Puritans, was a target for accusations. She was accused of attracting young girls like Abigail Williams and Betty Parris with enchanting stories from Malleus Maleficarum. These tales about sexual encounters with demons, swaying the minds of men, and fortune telling stimulated the imaginations of young girls and made Tituba an obvious target of accusations.

All of these outcast women fit the description of the "usual suspects" for witchcraft accusations, and nobody defended them. These women were brought before the local magistrates on the complaint of witchcraft and interrogated for several days, starting on March 1, 1692, then sent to jail. Other accusations followed in March: Martha Corey, Dorothy Good and Rebecca Nurse in Salem Village, and Rachel Clinton in nearby Ipswich. Martha Corey had voiced skepticism about the credibility of the girls' accusations, drawing attention to herself. The charges against her and Rebecca Nurse deeply troubled the community because Martha Corey was a full covenanted member of the Church in Salem Village, as was Rebecca Nurse in the Church in Salem Town. If such upstanding people could be witches, then anybody could be a witch, and church membership was no protection from accusation. Dorothy Good, the daughter of Sarah Good, was only 4 years old, and when questioned by the magistrates her answers were construed as a confession, implicating her mother. In Ipswich, Rachel Clinton was arrested for witchcraft at the end of March on charges unrelated to the afflictions of the girls in Salem Village.

SALEM

ACCUSATION & EXAMINATIONS

When Sarah Cloyce (Nurse's sister) and Elizabeth (Bassett) Proctor were arrested in April, they were brought before John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin, not only in their capacity as local magistrates, but as members of the Governor's Council, at a meeting in Salem Town. Present for the examination were Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth, and Assistants Samuel Sewall, Samuel Appleton, James Russell and Isaac Addington. Objections by John Proctor during the proceedings resulted in his arrest that day as well.

Within a week, Giles Corey (Martha's husband, and a covenanted church member in Salem Town), Abigail Hobbs, Bridget Bishop, Mary Warren (a servant in the Proctor household and sometime accuser herself) and Deliverance Hobbs (stepmother of Abigail Hobbs) were arrested and examined. Abigail Hobbs, Mary Warren and Deliverance Hobbs all confessed and began naming additional people as accomplices. More arrests followed: Sarah Wildes, William Hobbs (husband of Deliverance and father of Abigail), Nehemiah Abbott Jr., Mary Eastey (sister of Cloyce and Nurse), Edward Bishop, Jr. and his wife Sarah Bishop, and Mary English, and finally, on April 30, the Reverend George Burroughs, Lydia Dustin, Susannah Martin, Dorcas Hoar, Sarah Morey and Philip English (Mary's husband).

Nehemiah Abbott Jr. was released because the accusers agreed he was not the person whose specter had afflicted them. Mary Eastey was released for a few days after her initial arrest because the accusers failed to confirm that it was she who had afflicted them, and then she was rearrested when the accusers reconsidered.

In May, accusations continued to pour in, but some of those named began to evade apprehension. Multiple warrants were issued before John Willard and Elizabeth Colson were apprehended, but George Jacobs Jr. and Daniel Andrews were not caught. Until this point, all the proceedings were still only investigative, but on May 27, 1692, William Phips ordered the establishment of a Special Court of Oyer and Terminer for Suffolk, Essex and Middlesex counties to prosecute the cases of those in jail. Warrants were issued for even more people. Sarah Osborne, one of the first three accused, died in jail on May 10, 1692.

Warrants were issued for 36 more people, with examinations continuing to take place in Salem Village: Sarah Dustin (daughter of Lydia Dustin), Ann Sears, Bethiah Carter Sr. and her daughter Bethiah Carter Jr., George Jacobs, Sr. and his granddaughter Margaret Jacobs, John Willard, Alice Parker, Ann Pudeator, Abigail Soames, George Jacobs, Jr. (son of George Jacobs, Sr. and father of Margaret Jacobs), Daniel Andrew, Rebecca Jacobs (wife of George Jacobs, Jr. and sister of Daniel Andrew), Sarah Buckley and her daughter Mary Witheridge, Elizabeth Colson, Elizabeth Hart, Thomas Farrar, Sr., Roger Toothaker, Sarah Proctor (daughter of John and Elizabeth Proctor), Sarah Bassett (sister-in-law of Elizabeth Proctor), Susannah Roots, Mary DeRich (another sister-in-law of Elizabeth Proctor), Sarah Pease, Elizabeth Cary, Martha Carrier, Elizabeth Fosdick, Wilmot Redd, Sarah Rice, Elizabeth Howe, Capt. John Alden (son of John Alden and Priscilla Mullins of Plymouth Colony), William Proctor (son of John and Elizabeth Proctor), John Flood, Mary Toothaker (wife of Roger Toothaker and sister of Martha Carrier) and her daughter Margaret Toothaker, and Arthur Abbott. When the Court of Oyer and Terminer convened at the end of May, this brought the total number of people in custody to 62.

Cotton Mather wrote to one of the judges, John Richards, a member of his congregation, on May 31, 1692, voicing his support of the prosecutions, but cautioning him "do not lay more stress on pure spectral evidence than it will bear... It is very certain that the Devils have sometimes represented the Shapes of persons not only innocent, but also very virtuous. Though I believe that the just God then ordinarily provides a way for the speedy vindication of the persons thus abused."

SALEM

TRIALS

The Court of Oyer and Terminer convened in Salem Town on June 2, 1692, with William Stoughton, the new Lieutenant Governor, as Chief Magistrate, Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney prosecuting the cases, and Stephen Sewall as clerk. Bridget Bishop's case was the first brought to the grand jury, who endorsed all the indictments against her. Bishop was described as not living a puritan lifestyle for she wore black clothing and odd costumes which was against the puritan code. When she was examined before her trial, Bishop was asked about her coat which had been awkwardly “cut or torn in two ways”. This along with her immoral lifestyle accused her of a being a witch. She went to trial the same day and was found guilty. On June 3, the grand jury endorsed indictments against Rebecca Nurse and John Willard, but it is not clear why they did not go to trial immediately as well. Bridget Bishop was executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

More people were accused, arrested and examined, but now in Salem Town, by former local magistrates John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin and Bartholomew Gedney who had become judges of the Court of Oyer and Terminer. Roger Toothaker died in prison on June 16, 1692.

June 30 through early July, grand juries endorsed indictments against Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin, Elizabeth Proctor, John Proctor, Martha Carrier, Sarah Wilds and Dorcas Hoar. Only Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Susannah Martin and Sarah Wildes, along with Rebecca Nurse, went on to trial at this time, where they were found guilty, and all five were executed by hanging on July 19, 1692.

Mid-July, the constable in Andover invited the afflicted girls from Salem Village to visit with his wife to try to determine who was causing her afflictions. Ann Foster, her daughter Mary Lacey Sr., and granddaughter Mary Lacey Jr. all confessed to being witches. Anthony Checkley was appointed by Governor Phips to replace Thomas Newton as the Crown's Attorney when Newton took an appointment in New Hampshire.

In August, grand juries indicted George Burroughs, Mary Eastey, Martha Corey and George Jacobs, Sr., and trial juries convicted Martha Carrier, George Jacobs, Sr., George Burroughs, John Willard, Elizabeth Proctor and John Proctor. Elizabeth Proctor was given a temporary stay of execution because she was pregnant. August 19, 1692, Martha Carrier, George Jacobs Sr., George Burroughs, John Willard and John Proctor were executed.

In September, grand juries indicted eighteen more people. The grand jury failed to indict William Proctor, who was re-arrested on new charges. On September 19, 1692, Giles Corey refused to plead at arraignment, and was subjected to peine forte et dure, a form of torture in which the subject is pressed beneath an increasingly heavy load of stones, in an attempt to make him enter a plea. Four pleaded guilty and eleven others were tried and found guilty.

September 20, Cotton Mather wrote to Stephen Sewall, the clerk of the court: "That I may be the more capable to assist in lifting up a standard against the infernal enemy..." requesting "... a narrative of the evidence given in at the trials of half a dozen, or if you please, a dozen, of the principal witches that have been condemned."

September 22, 1692, eight more were executed, "After Execution Mr. Noyes turning him to the Bodies, said, what a sad thing it is to see Eight Firebrands of Hell hanging there." One of the convicted, Dorcas Hoar, was given a temporary reprieve, with the support of several ministers, to make a confession of being a witch. Aged Mary Bradbury escaped. Abigail Faulkner Sr. was pregnant and given a temporary reprieve (some reports from that era say that Abigail's reprieve later became a stay of charges).

SALEM SUPERIOR COURT 1693

In January 1693, the new Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize and General Gaol Delivery convened in Salem, Essex County, again headed by William Stoughton, as Chief Justice, with Anthony Checkley continuing as the Attorney General, and Jonathan Elatson as Clerk of the Court. The first five cases tried in January 1693 were of the five people who had been indicted but not tried in September: Sarah Buckley, Margaret Jacobs, Rebecca Jacobs, Mary Whittredge and Job Tookey. All were found not guilty. Grand juries were held for many of those remaining in jail.

Charges were dismissed against many, but sixteen more people were indicted and tried, three of whom were found guilty: Elizabeth Johnson Jr., Sarah Wardwell and Mary Post. When Stoughton wrote the warrants for the execution of these women and the others remaining from the previous court, Governor Phips pardoned them, sparing their lives. In late January/early February, the Court sat again in Charlestown, Middlesex County, and held grand juries and tried five people: Sarah Cole (of Lynn), Lydia Dustin & Sarah Dustin, Mary Taylor and Mary Toothaker. All were found not guilty, but were not released until they paid their jail fees.

Lydia Dustin died in jail on March 10, 1693. At the end of April, the Court convened in Boston, Suffolk County, and cleared Capt. John Alden by proclamation, and heard charges against a servant girl, Mary Watkins, for falsely accusing her mistress of witchcraft. In May, the Court convened in Ipswich, Essex County, held a variety of grand juries who dismissed charges against all but five people. Susannah Post, Eunice Frye, Mary Bridges Jr., Mary Barker and William Barker Jr. were all found not guilty at trial, putting an end to the episode.

SALEM

LESSONS

As

you read this remember that none of the people executed as witches were in

fact possessed of any supernatural powers, but were simply put to death on

the say so of another person with a grudge. Shocking that may be to us

today, but there is nothing different in that, than the landslide of false

accusations against men who for one reason or another have fallen foul in a

relationship. Today, women in the UK can accuse a man of assault, child

abuse and rape - and he will be convicted unless he can prove his innocence.

Put another way, a woman only needs to get a man alone for a few moments, so

that there are no witnesses, and her accusation will be taken as genuine.

These are the new witches. The women who falsely accuse men of sexual

crimes, driven by revenge.

STATISTICS

Current scholarly estimates of the number of people executed for witchcraft vary between about 40,000 and 100,000. The total number of witch trials in Europe which are known to have ended in executions is around 12,000.

Prominent contemporaneous critics of witch hunts included Gianfrancesco Ponzinibio (fl. 1520), Johannes Wier (1515–1588), Reginald Scot (1538–1599), Cornelius Loos (1546–1595), Anton Praetorius (1560–1613), Alonso Salazar y Frías (1564–1636), Friedrich Spee (1591–1635), and Balthasar Bekker (1634–1698).

Some authors claim that millions of witches were killed in Europe, while modern scholarly estimates place the total number of executions for witchcraft in the 300-year period of European witch-hunts far lower. William Monter estimates 35,000 deaths (see table below), historian Malcolm Gaskill 40,000–50,000.[34] About 75 to 80 percent of those were women.

THE

END OF WITCH HUNTS IN EUROPE

End of European witch hunts in the 18th century

In England, Scotland and Ireland, between 1542 and 1735 a series of Witchcraft Acts enshrined into law the punishment (often with death, sometimes with incarceration) of individuals practising, or claiming to practice witchcraft and

magic.

The last executions for witchcraft in England had taken place in 1682, when Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susanna Edwards were executed at Exeter. In 1711, Joseph Addison published an article in the highly respected The Spectator journal (No. 117) criticizing the irrationality and social injustice in treating elderly and feeble women (dubbed Moll White) as witches. Jane Wenham was among the last subjects of a typical witch trial in

England in 1712, but was pardoned after her conviction and set free. Kate Nevin was hunted for 3 weeks and eventually suffered death by Faggot and Fire at Monzie in Perthshire, Scotland in 1715. Janet Horne was executed for witchcraft in

Scotland in 1727. The final Act of 1735 led to persecution for fraud rather than witchcraft since it was no longer believed that the individuals had actual supernatural powers or traffic with

Satan. The 1735 Act continued to be used until the 1940s to prosecute individuals such as spiritualists and Gypsies. The act was finally repealed in 1951.

The last execution of a witch in the Dutch Republic was probably in 1613. In

Denmark this took place in 1693 with the execution of Anna Palles. In other parts of Europe, the practice died down later. In

France the last person to be executed for witch craft was Louis Debaraz in 1745. In Germany the last death sentence was that of Anna Schwegelin in Kempten in 1775 (although not carried out). The last known official witch-trial was the Doruchów witch trial in Poland in 1783. Two unnamed women were executed in Posnan, Poland, in 1793, in proceedings of dubious legitimacy.

Anna Göldi was executed in Glarus, Switzerland, in 1782, and Barbara Zdunk in Prussia in 1811. Both women have been identified as the last person executed for witchcraft in

Europe, but in both cases, the official verdict did not mention witchcraft, as this had ceased to be recognized as a criminal offense.

METAPHORICAL

USE

In modern terminology 'witch-hunt' has acquired usage referring to the act of seeking and persecuting any perceived enemy, particularly when the search is conducted using extreme measures and with little regard to actual guilt or innocence. It is used whether or not it is sanctioned by the government, or merely occurs within the "court of public opinion".

The first such use reported by the Oxford English Dictionary dates to 1932. Another early instance is George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia (1938). The term is used by Orwell to describe how, in the Spanish Civil War, political persecutions became a regular occurrence.

The term is used when a hunt for wrongdoers becomes abused, and a defendant can be convicted merely on an

accusation. For example, in the History Channel documentary America: The Story of Us, narrator Liev Schreiber explains that "the search for runaway

slaves becomes a witch hunt. A black man can be convicted with merely an accusation. Unlike white people, they do not have the right to trial by jury. Judges are paid ten dollars to rule them as slaves, five to set them free."

Use of the term was popularized in the United States in the context of the McCarthyist search for communists during the Cold War, which was discredited partly through being compared to the Salem witch trials.

From the 1960s, the term was in wide use and could also be applied to isolated incidents or scandals, specifically public

smear-campaigns against individuals. The phenomenon of day care sex abuse hysteria, most notably the McMartin preschool trial of 1984 to 1990, is another iconic example of a moral panic which saw day care providers accused of what was dubbed "satanic ritual abuse", i.e. the charge of physical and sexual child abuse out of an alleged Satanist motivation. The case and the associated media coverage has been frequently termed a witch-hunt by commentators and social researchers. More generally the societal reaction to child

sexual abuse has been criticized as a witch-hunt by some academics and commentators since the early 1990s.

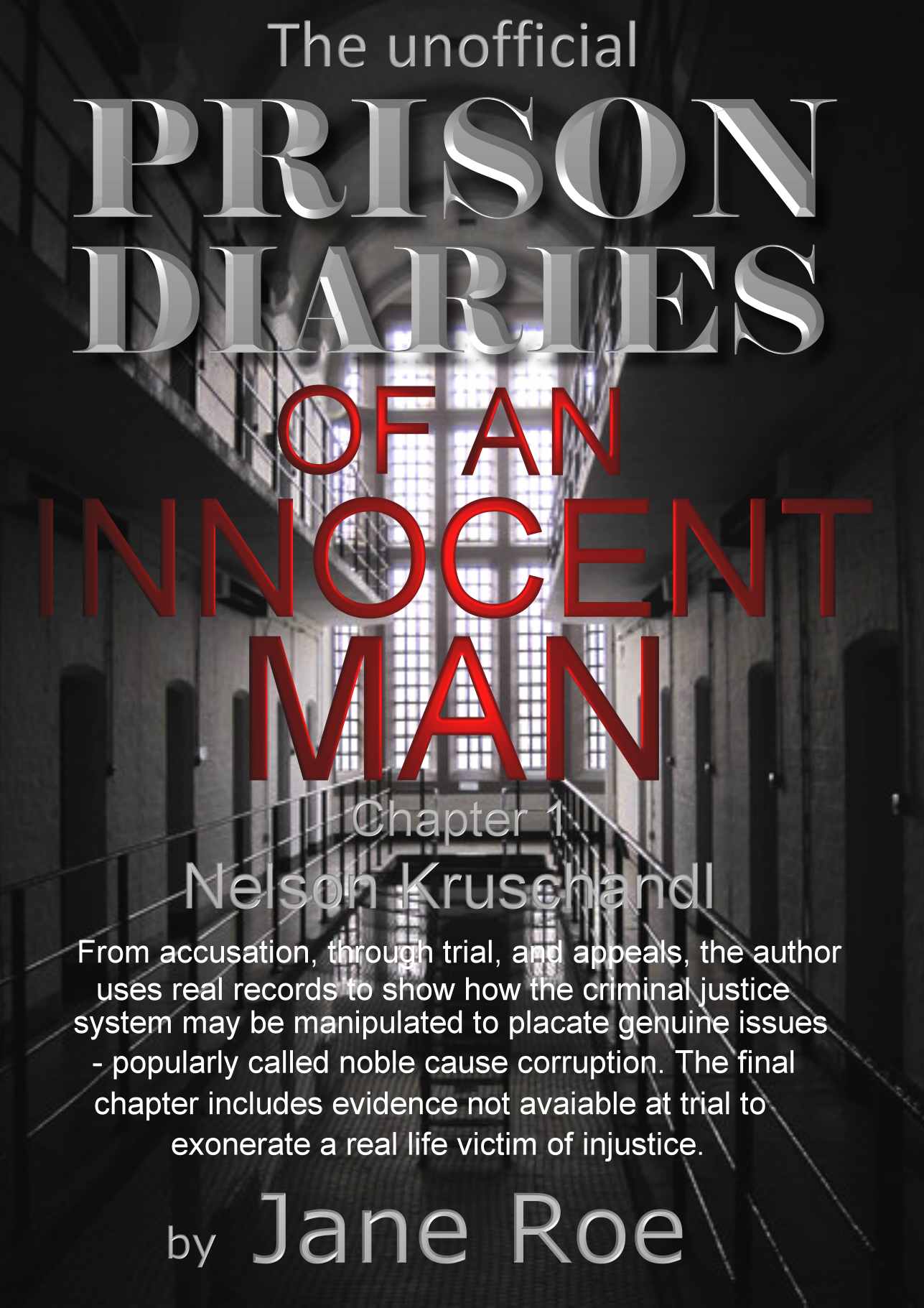

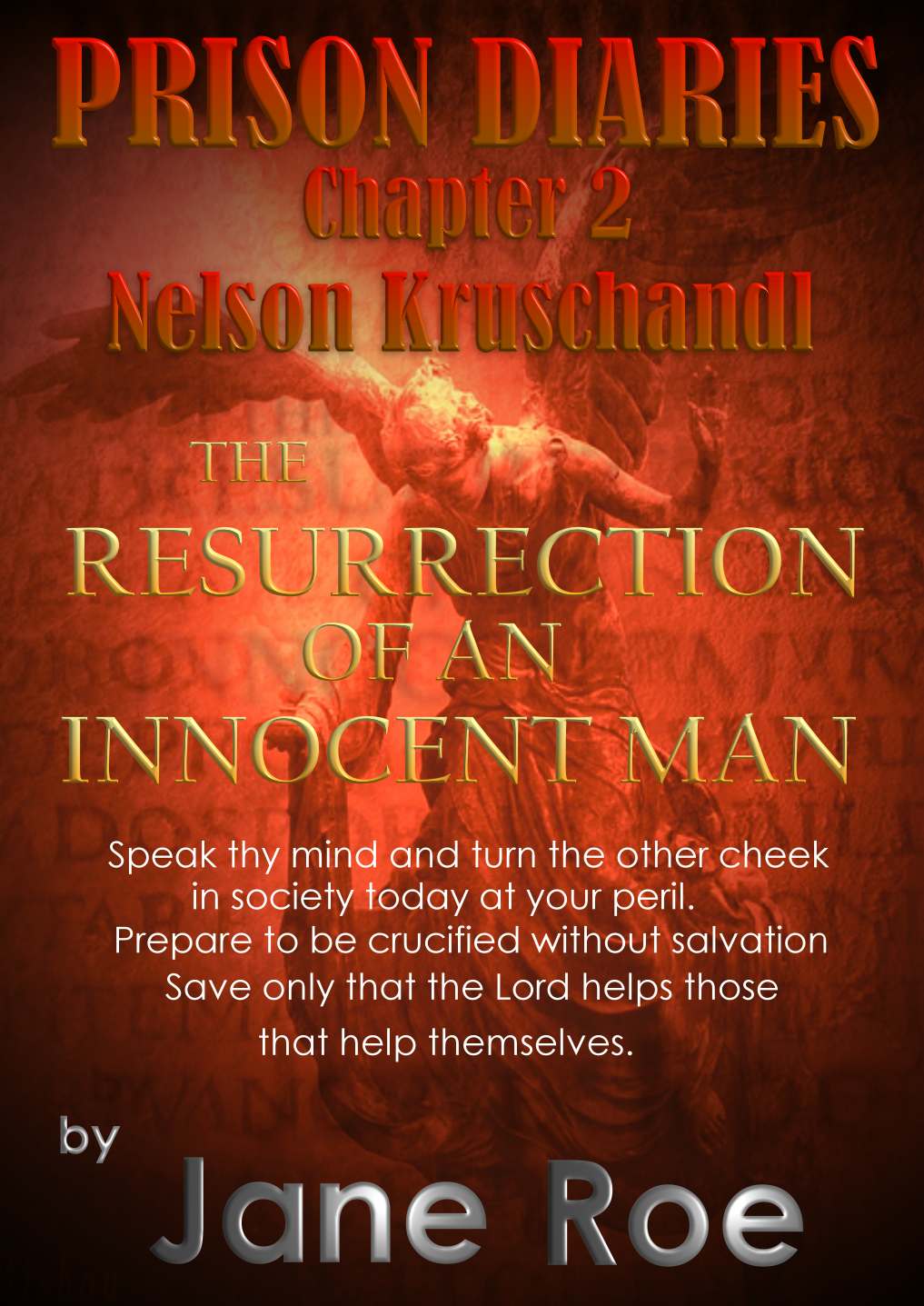

They

crucified him. The local police produced evidence at his trial that was

guaranteed to convict him, then made sure the local

press

published details of his conviction

so that nobody would believe

his revelations about corruption in local government. The so-called forensic

evidence turned out to be junk science, a natural feature that was

understood in the USA to be just that - had not found its way into UK

guidance. Presented in court as controversial, what the Crown's expert meant

was that US studies did not accord with UK studies at the time. Two months

after the trial the UK studies recognised the US studies. The victim of this

injustice would not learn that until three years into his sentence. The CCRC

did not tell him about the cases they had referred to the Court of Appeal -

and in his case, they turned a blind eye. This is a true story based on

official documents. Not to be published until after the subject's appeals in

Europe are heard.

His

barrister didn't show the jury the accused' diaries, he should have, because

the girl's mother reminded the accused to send Valentines cards every year -

which she, err, seems to have forgotten to mention to the court. She

also forgot to tell the prosecution about the existence of her own diaries.

These diaries reveal that the accused was not alone with the girl as she had

claimed. Why do you suppose her mother might hide this information?

The accused was instructed not to venture why the girl should make up her

story by his barrister, but of course he has a good idea. Sadly, that cannot

be revealed just yet for legal reasons. He did say he could forgive a 15

year old for some kind of unthinking hormone driven revenge for not doing

what she had wanted, but not a mature woman - who would have known better.

The girl wanted the accused to get back together with her mother having

called off an engagement.

It's an or-else situation and the accused was threatened - which information

the defence lawyers failed to introduce - despite instructions to the

contrary.

Local newspapers breached a Court Order prohibiting coverage, and published

mid-trial, which to us seem the most damaging time to publish, to virtually

guarantee conviction. The jury were of course reading those newspapers.

Nearly all the local papers published at the same time - in orchestrated

fashion - obviously from a shared source; presumably the reporter attending.

Is that responsible reporting? They knew such coverage would influence the

thinking of jurors and the public.

Once they had convicted the victim of this injustice, the Crown tried to

prevent him publishing his story. Why would they do that? Fortunately, Judge

Cedric Joseph (this was his last case) was persuaded by barrister Michael

Harrison, that that would breach the chaps human rights. The Judge agreed,

subject to not naming the girl or her mother.

We think that the Crown's reluctance is to do with the way they obtained

their conviction. It was based on medical testimony, which itself was based

on out of date guidance from the Royal College of Paediatric and Child

Health from 1997. New guidance was issued in 2008, just one month after the

trial. Why did the Crown not wait the extra month before going to trial?

Well, we know the answer to that, the new guidance confirmed that certain

internal marks are naturally occurring. The prosecution told the jury (or,

rather, allowed their pet witness to say it for them - which amounts to the

same thing) that they were supportive of the allegations - which was a

deception on the part of the Crown.

The Crown had kept the defence waiting for more than 18 months and delayed

matters by refusing to hand back vital computer information that they'd

confiscated - claiming they might find pornographic images. Of course the

Crown were just making this up and instead of letting the jury know that all

of the accused' computers were image free, they refused to confirm the

results of their investigations! Normally, a report on confiscated machines

is supplied to the defence. Don't you think the jury should have known that

this man's computers were clean?

You'll have to wait for the subject's appeals in the ECHR to conclude before

this book is published. Maybe then we'll see an official version in

2016/2017? European appeals take 4 years on average, from the date of lodge.

But first you have to exhaust any domestic remedy. He has finally, as of

February 2013.

This man served nearly four years for a crime he did not commit. If you

would like to know more about this developing story, please Contact Us.

LINKS

and REFERENCE

GNU

free documentation license

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Left-Hand_Path_and_Right-Hand_Path

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceremonial_magic

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occult

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jesus_Christ

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salem_witch_trials

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witch-hunt

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witchcraft_Act_of_1735 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_Hopkins

|